March 30, 2018

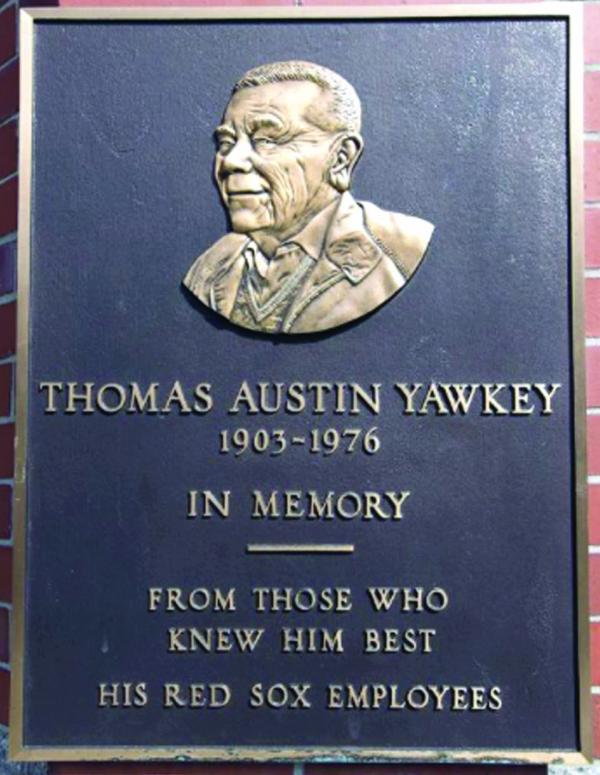

The Boston Red Sox, who have initiated a public process to change the name of Yawkey Way, are getting plenty of pushback from prominent apologists for the late Red Sox owner who claim that he has been unfairly portrayed as a racist.

His defenders note that the Yawkey Foundation, a charity that he and his wife created, has been a force for good since their deaths. Some, like former Sox hurler Jim Lonborg, say that Yawkey “changed” over the course of his life.

Yawkey’s most passionate defenders include leading Bostonians who have a connection to the foundation. Some are trustees, like Rev. Ray Hammond, who has become the most outspoken opponent of the name change. He and others, like Cardinal Sean O’Malley, whose various Catholic missions are aided by the fund’s largesse, signed a letter to the Boston Public Improvement Commission opposing the street name change that said, in part: “We believe it is not overstating things to say that removing his name from Fenway Park will forever taint his legacy, both as the historic owner of the Red Sox and throughout the city of Boston.”

With respect, that is overstating things.

The current Red Sox ownership under John Henry has acknowledged the good works of the Yawkey charities, but it isn’t happy that Yawkey’s decidedly poor record on racial integration — both on and off the playing fields during his ownership years— hamper their present-day efforts to make Fenway welcoming to everyone, especially people of color. The Red Sox — and their abutters— have every right to seek to present their property, their team, and their brands to the public in a new way.

Yawkey’s boosters also grossly understate the impacts of the former regime’s well-documented and deeply disturbing practice of discrimination over many years. This history is not just about being the last to call up an African-American player (12 years after Jackie Robinson joined the Dodgers.) It’s about an insidious, institutionalized brand of racism that polluted the team for years and helped further cement Boston’s national reputation as a hostile environment for black Americans.

Last Thursday’s hearing of the BPIC included testimony from Walter Carrington, 88, a former member of the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD). An Army veteran who also served in the Peace Corps and as US ambassador to Senegal, Carrington felt compelled to share his story about his own investigations into Yawkey’s business practices in the 1940s and ’50s.

Carrington was called in to probe Yawkey and his front office and not only because they wouldn’t field black players, but, he said, because they didn’t have any black employees at any level. It was a disgraceful record that was well known to black Bostonians and people across the nation.

Carrington’s testimony was that the Red Sox and Yawkey only begrudgingly agreed to bring up their first black player, Elijah “Pumpsie” Green, in 1959 after his MCAD investigation found chronic wrong-doing and forced the issue.

For Carrington, there was an immediate price to be paid for doing his job. As an MCAD commissioner, he served at the discretion of the governor and the Governor’s Council, which at the time (1950s and ’60s) was chaired by Dorchester’s Sonny McDonough. In his testimony, Carrington said that after his hearings on the Red Sox, McDonough called him into his office and “reamed me out. “He told me that Mr. Yawkey and others were unhappy and he was going to see that I was not re-appointed.”

Rev. Hammond, who also testified on Thursday and called the Red Sox behavior at that time “sad, painful, and a reality that Red Sox and Boston have to own”— dismisses the idea that this outrageous pattern by Yawkey’s company should “unfairly tarnish the legacy of [the] man.”

What’s unfair is the revisionism of the Yawkey apologists who would hold powerful men blameless for installing a systematic and sustained period of Jim Crowism in one of our town’s most important institutions. It is offensive for Cardinal O’Malley and his co-signers to suggest to modern-day Bostonians that Yawkey’s discriminatory ways were “the norm” back then, and so should thus be ignored.

Perhaps they will choose to ignore it — and that’s surely their right. But the Red Sox have every right to acknowledge it — to “own it”—and to then choose to move away from it.

We hope the Red Sox will take steps to put the Yawkey era in the proper context— as a big part of the team’s history, but not one to be so elevated in a current-day depiction of what the Red Sox are all about. And we hope that the city Commission will accept the request to change Yawkey Way back to Jersey Street.

– Bill Forry