December 12, 2022

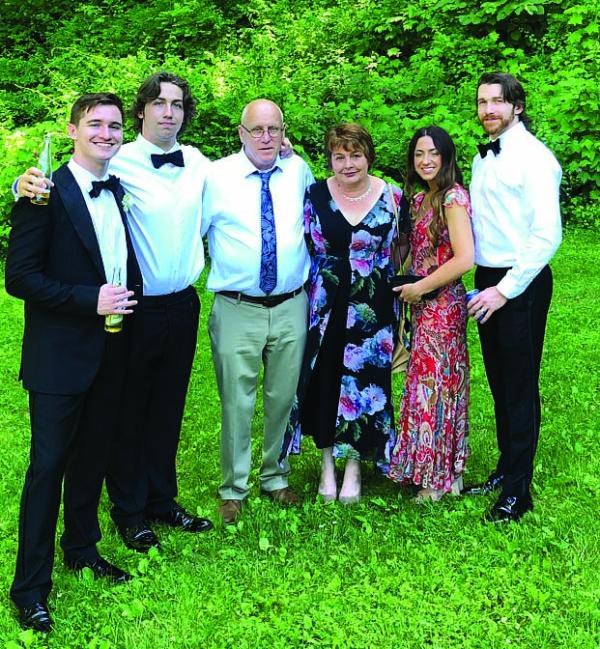

Mary Swanton’s family: Sons Michael and Kevin, husband Albert, Mary, daughter-in-law Sonia, and son Seán. Swanton family photo

Mary Swanton currently lives in Milton with her husband, Albert. A union carpenter in Boston and a native of Skibbereen in West Cork, he was a member of the world famous Skibbereen Rowing Club. Their oldest son, Seán, 28, served in the United States Marine Corps and lives in Wakefield with his wife Sonia. Their two younger sons—Kevin, 21, and Michael, 19, both play college rugby. Swanton adds that Michael has inherited her Dad’s tenor voice which, she says, “is very meaningful.”

“They grew up without cousins, without that immigrant connection to family. However, the continued presence of Ireland in Boston exposed them to their own heritage,” said Swanton. “Those who came before us worked hard to keep strong the ties that bind us to home”

“It bothers me that there is a distinction between Irish-born parents like Albert and I and the fact that our children are Irish American,” she added. “I think we need to just turn the phrase a little bit and realize that we are all Boston Irish, regardless as to our connection. We are not an Irish and Irish American family.”

Swanton says she loves to travel with Albert for her sons’ rugby games and to spend time with her “Mother Teresa” in Limerick, where she notes a kind of separation that can only be bridged by memory.

“It takes going home to Limerick to realize that you can’t go back because that Ireland doesn’t exist anymore,” she said. “You’re going to the house, your childhood home, but everything else around it has changed. Your connections have faded and you realize that time passes on both sides of the ocean. I am always so proud to be Irish but, more importantly, I’m privileged to be Irish in Boston.”

If a homeland can be a place without boundaries, that was the case in January of this year, with response to the murder of Ashling Murphy in Ireland’s Co. Offaly. The 23-year-old music teacher was killed near her hometown, Tullamore, while out for a jog along a canal. It happened around four in the afternoon—before dark. She was on a path named after Fiona Pender, a woman from the same town who had vanished without a trace in 1996. What happened to Murphy was quickly seized upon as a reminder of the persistent threat of violence against women.

Murphy was also a traditional Irish musician, playing fiddle and tin whistle, even starting to learn uilleann pipes, and she toured Ireland and the UK with the national folk orchestra from Comhaltas Ceoltóirí. Along with the teaching and music, Swanton knew of one other connection: Murphy’s sister Amy, with the aid of a J-1 visa, had spent a summer working at Greenhills Bakery in Adams Village. “Amy stood out because of her musical background,” Swanton recalled. “We got the word out on social media.”

Two days after the murder, a locally organized candlelight vigil took place in Tullamore Town Park, within view of the crime scene. Murphy’s father, Ray Murphy, sang his daughter’s favorite song, “When You Were Sweet Sixteen.” It was a vaudeville hit from 1898, re-popularized in a 1981 recording by The Fureys, a band in which Murphy’s father had played.

The same day, a vigil with traditional music took place outside the parliament buildings in Dublin, starting a little after at 4 p.m, when the candle lights were still noticeably faint. Slow traditional music could also be heard in Limerick City, where Murphy had graduated from college just a few months earlier, and “When You Were Sweet Sixteen” would re-echo at a vigil in London.

There were more vigils, from Kerry to Belfast, from Sligo to Waterford, Cardiff, Liverpool, Glasgow, Edin-burgh, Brisbane, Vancouver, San Francisco, Yonkers, even somewhere by the water in Dubai. And, on a cold Sunday in Dorchester, about two hundred people gathered in a parking lot behind Greenhills bakery, with music by the Boston chapter of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann and a song about Murphy’s hometown, sung by a man from Tullamore known as Blackie Quinn.

“It was a proud night,” said Swanton. “It’s what we do.” It wasn’t all the work of the IPC, but it reminded her of the adage: “Ní neart go cur le chéile” / There’s no strength without unity.”