March 18, 2021

by Sean Smith

Boston Irish Contibutor

Full Tilt, “Full Tilt Live” • Oh, my. This is one of those albums that hits so many buttons beyond the visceral pleasure of listening to it because of what is represented in the joining of these skills, talents, and experience.

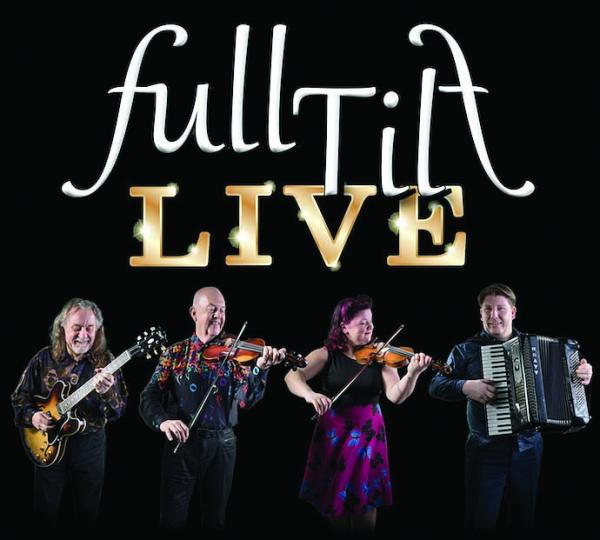

Full Tilt is a union of different generations as well as music traditions: Manus McGuire, member of such bands as Buttons and Bows and Moving Cloud and champion of the Sligo fiddle, but also greatly interested in other styles; accordionist Alan Small, a veteran of the Scottish ceilidh band scene; Shetland/Scottish fiddler-pianist Gemma Donald, a past finalist for BBC Young Traditional Musician of the Year; and Shetlander Brian Nicholson, a guitarist and vocalist with a variety of musical tastes and interests.

The quartet seamlessly merges Irish, Scottish, and Shetland tunes, including originals by McGuire, Donald, and Small and others by the likes of Charlie Lennon, Nollaig Casey, April Verch, Donald Shaw, and Ed Reavy. Full Tilt also is able to shift between different incarnations, sounding fully comfortable in archetypal ceilidh band (Irish or Scottish) mode, modern Celtic folk revival vein, or a Saturday-night-in-the-pub vibe.

Most of all, they just sound so damn good. The virtuosity and chemistry displayed by McGuire and Donald, whether playing in unison or – better yet – in harmony, is energizing. Small’s accordion (which includes a MIDI-enhanced bass) provides a deft, rhythmic punch and he’s a fine melody player, too. Nicholson’s electric guitar lends versatility, adding complementary and creative shades of rock, country, blues, and jazz.

It’s a pure delight to hear McGuire and Donald whip through some old familiars, like “The Barrowburn Reel,” “Ten Penny Bit,” the absurdly intricate “Belfast Hornpipe,” and a medley encompassing Ed Reavy’s “Maudabawn Chapel,” traditional tunes “The Cameronian” and “Dawn Hornpipe,” and Donald Shaw’s “The Shetland Fiddler.” McGuire and Donald also each get to lead a set of their own instrumentals: McGuire’s reels “Howling at the Moon/Sunset Over Scariff/Gortcommer Welcome” and Donald’s jigs “Johnny Barton’s Fiddle/Elma’s Big Break/Capers in Culbokie.” Their adaptation of Nollaig Casey’s slow air “Lios Na Banriona (Fort of the Fairy Queen),” meanwhile, is breathtakingly beautiful.

Full Tilt displays their inventive, fun spirit on the outstandingly well-crafted “Pink Panther Set”: Donald – whose piano chops are in the spotlight here – plays the intro to the famous Henry Mancini-penned theme, to which Nicholson unfurls a genuine slow-burn rock/blues solo, while over them Small breaks into the classic trad Irish “Morrison’s Jig”; then McGuire picks up the melody and the trio is off and running without a hitch, segueing into J.S. Crofts’ “Rosemary Lane” and Charlie Lennon’s dearly loved “Handsome Young Maidens.”

Nicholson adds another dimension with his selections of songs by Shetland writers, in robust Shetland dialect: John Barclay’s “Isle O’Gletness” is homage to home and hearth, McGuire and Donald’s fiddles making it sound like a sweet Texas waltz; the sprightly maritime “Farewell Tae Yell,” by Larry Robertson and Robert Tait, punctuated by a nifty recurring 2/4 riff by fiddles and accordion; and “Du Picked a Fine Time ta Faa-by Dastreen,” Bobby Tulloch’s witty Shetland take on “You Picked a Fine Time to Leave Me, Lucille.”

Yet another undeniable asset of this album is that, as the title indicates, it was recorded live, back during the band’s 2019 tour. If you think you’ve somehow become inured to listening to music at a remove, “Full Tilt Live” reminds you of what a special thing an in-person event is: the in-the-moment sensation, the rapport between band and audience, the sheer joy of applauding and cheering a great performance. Listening to this album isn’t exactly like being there, obviously, but you’ll get more than enough pleasure out of it. [fulltilt.band]

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Salt House, “Huam”; Jenny Sturgeon, “The Living Mountain”; Lauren MacColl, “Landskein” • Scottish trio Salt House hit the trifecta over this past year, with its third album and solo releases by two of its members coming in the space of eight months. Each recording is enjoyable on its own terms, but this convergence of the three also offers an opportunity to appreciate the individual talents, interests, and personas that constitute a band lauded as much for its defining artistic vision as well as its musicianship.

Salt House originally began with a different name and went through a couple of configurations – they released their first album as Salt House in 2013, “Lay Your Dark Low,” as a quartet – but since 2018 has consisted of Ewan MacPherson (guitars, dulcimer, vocals) Lauren MacColl (fiddle, viola, glockenspiel, vocals) and Jenny Sturgeon (guitar, keyboards, dulcimer, vocals). The trio has fashioned a sound that marries contemporary acoustic styles, such as 1960/70s UK blues-folk a la Pentangle, with introspective, pastoral songwriting that is deeply ingrained in folk song and literary traditions.

"Huam" – the Scots word for the call of an owl – affirms Salt House's self-described interest in "place, politics and landscape," with an emphasis on environments that bring comfort and reassurance in the midst of turbulence. But implicit in their songs' ardor for rural shades and peaceful glens is a belief that, rather than escaping to nature as refuge or weekend getaway, one should embrace it as a commitment worth undertaking.

Such is the case with "Mountain of Gold," sung in gorgeous fashion by all three with a part-hymn, part-lullaby quality to it ("When the hill awakens from sleeping/And the winter runs from the land/When the burn continues its singing/When spring reveals its hand"), and "The Same Land," a lament achingly voiced by Sturgeon and MacPherson (“Hurry down on stoney ground/Through the fractious never ending/It's all mixed up and descending/Until we find the time to breathe") – with harmonium drone and distant, slightly distorted electric guitars – not to mention their setting of Emily Dickinson's "Hope Is the Thing with Feathers."

But Salt House does not gloss over the darkness within the natural world, as evidenced by "William and Elsie," their chilling adaptation of a Danish ghostly-lover ballad in which the titular William describes the afterlife ("Whenever thou art smiling, when thy bosom gladly glows/My grave in yonder dark kirk yard is hung with leaves of rose/Whenever thou are weeping, and thy dreadful sadness reigns/My grave in yonder dark kirk yard is filled with living pain"), and an enthralling "Lord Ullin's Daughter," Thomas Campbell's tragic poem of lovers fleeing the fury of her father, straight into the wrath of the elements ("By this the storm grew loud apace/The water-wraith was shrieking/And in the scowl of heaven each face/Grew dark as they were speaking").

Listening to Sturgeon’s “The Living Mountain,” it’s clear how much she contributes to Salt House’s artistic vision. Born in Aberdeenshire and now living in Shetland, Sturgeon has a PhD in seabird ecology, and her songwriting reflects an abiding interest in, and fascination with, the sights, sounds and rhythms of nature – and how humans perceive them (or perhaps fail to adequately). Her 2017 EP, “The Wren and the Salt Air,” was inspired by the unique bird populations of the remote St Kilda island group; that album included field recordings of wild birds and island weather.

Here, Sturgeon has taken inspiration – and the album’s title – from “The Living Mountain,” a memoir by Anna “Nan” Shepherd (1893-1981) of her experiences and impressions of walking in the Cairngorns mountain range. The songs here are richly lyrical, vivid, deeply felt meditations equally steeped in senses and science. Sturgeon follows the structure of the book – the tracks are named for each chapter, in order – and focuses on some aspect, feature or sensation Shepherd observed or felt during her travels through the Cairngorns.

Shepherd wasn’t just out for a pleasure jaunt to gaze at pretty flowers and photogenic wildlife: She gave herself over completely to the mountains and their environs, and Sturgeon conveys this in songs like “The Recesses” (“Cracks and fissures/Fractures forced and falling fair/in the dark and hidden/You don’t really know what’s there”) and “Frost and Snow” (“Wild winds keen/A cornice formed, overhang it leans/Prevailing force, sastrugi like the waves/A sea of ice, sea of ice”).

Sturgeon also adapted a couple of Shepherd’s poems for the album: “Man” – which appears on “Huam” under its original name, “Fires” – and “Water” (known as “Singing Burn”).

The melodies and arrangements devised by Sturgeon thoroughly complement the lyrics. She accompanies herself variously on guitar, piano, harmonium, dulcimer, whistle, and synthesizer, with occasional help from Grant Anderson (bass, vocal), Mairi Campbell (viola, vocal) and Sua-Lee (cello). On “The Group,” piano and strings help proclaim the Cairngorns as both a rich realm of life and a lifeforce in of itself (“I’ve been witness through the ages/Marked changes and uses”). “The Plants” is an introduction to the mountains’ diversity of flora, with a joyous, proud refrain, “We are of the soil.” “Water,” accompanied for the most part by a single drone note, animates the springs, creeks, rivers, and other bodies of water, and their interrelationship with the terrain (“From trickling burn to lowland plain/The spring she sees it all”).

In the concluding track, “Being,” piano and strings embrace Shepherd’s/Sturgeon’s benediction, a call to be mindful of our true selves, set loose from distraction: “Living through the senses/As we search/To find out what’s real.”

As in “The Wren and the Salt Air,” Sturgeon makes use of assorted field recordings from the Cairngorns National Park throughout the album, enabling the mountains and its denizens to lend their own voices.

(Sturgeon has recorded “The Living Mountain Podcast,” conversations with artists, writers, and ecologists about their connections with the mountains, outdoor places, and how they inspire and influence their work. She’s also working on a film complement to “The Living Mountain.”)

MacColl’s “Landskein” has a simple, straightforward premise, consisting of airs and other slow or moderate-speed tunes from the Highland fiddle tradition. It’s literally a solo effort, except for four tracks on which James Ross provides sparse, sensitive piano accompaniment; some of the other tracks include a faint drone from a pump organ or an electric guitar, or additional plucked or bowed strings on fiddle or viola.

While there is some variance of tempo, pace and time signatures, “Landskein” has a very pleasing unhurried, contemplative feel to it – and a spacious sound as well, due in no small part to it being recorded in a village hall near Loch Ness. The album is like an aural microscope, bringing up close every bow stroke, no matter how soft or faint. And the diversity of character among the tunes is profound, from the stately, sedate “Mrs. McIntosh of Raigmore” to the supernatural edginess of “Sproileag (An Untidy Witch),” the quiet, intense vibrato of “Air Mullach Beinn Fhuathais” to the unusual cadence in “‘Lal, Ial,’ Ars' a' Chailleach,” which came to MacColl from a singer (Rona Lightfoot) rather than an instrumentalist.

Thematically, the title “Landskein” – a reference to the lifelines that bind people (like MacColl in this case) with landscape, memories, stories and traditions – is of a piece with “Huam” and “The Living Mountain.” The album also helps one better appreciate the traditional roots and styles within MacColl’s fiddling, set as they are in the contemporary milieu of Salt House.

MacPherson – a member of famed folk-rock fusion band Shooglenifty – is the odd one out here, at least in terms of a solo recording. But on “Huam” his gifts as a songwriter are abundant, and bring more of an overt social-justice perspective to the Salt House gestalt: “All Shall Be Still” offers reassurance of finding tranquility in a time of noise and unrest (“Politicians are arguing over numbers and names/Their lies are lost when the waves come roaring”); “If I Am Lucky” considers the risks of taking, or not taking, action (“If I am lucky this wine will drown my sorrows/If I am lucky the world is cooling down/But I’ve believed so many of their stories/I must be bold and stand my ground”).

“The Union of Crows,” which ends the album, is a particularly fascinating MacPherson composition. The title and recurring lyric is a play on “the Union of the Crowns,” the problematic unification of England, Scotland, and Ireland that accompanied the 1603 accession to the throne of James I. Although his song doesn’t relate directly to that historical event, MacPherson explains that the phrase suggested to him the disenfranchisement and alienation of people at the hands of the powerful, who churn out consumer goods or other sources of distraction while socioeconomic inequalities and other perils mount.

“So while the others toil on, with golden light bright in their eyes

We’ll stop our lives from passing by, we’ll stop the murder with just our hands

And as a river slowly grows, with rain from off surrounding hills

We will not heed the darkened wing of our great union of crows”

Collectively or individually, the members of Salt House will be enriching Scottish folk music for some time to come, and that’s reason to cheer. [“Huam” is available at salthouse.bandcamp.com, through which links to “The Living Mountain” and “Landskein” may be found.]