March 7, 2021

by Peter F. Stevens

Boston Irish Staff

It’s off—again.

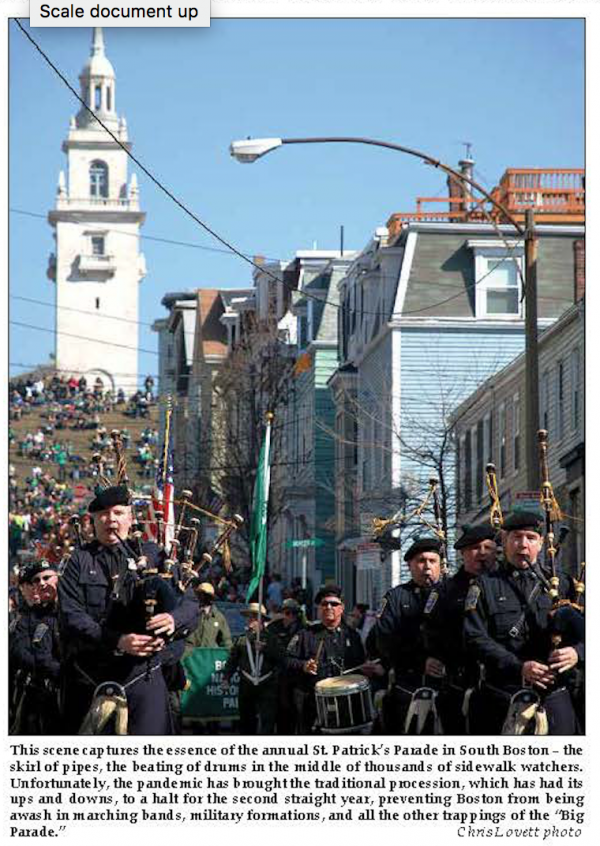

This March, the skirl of pipes, the beat of drums, and the tramp of thousands of feet will not echo above the streets of Southie.

For the second straight year, Covid-19 has brought the traditional procession to a halt, preventing Boston from being awash in marching bands, military formations, and all the other trappings of the “Big Parade.” Those trappings, of course, include dense crowds of all ages, an ocean of green beer, green plastic derbies, “Kiss Me, I’m Irish” badges, and faces—some, but far from all, reflecting various stages of inebriation and emblazoned with painted shamrocks or the Irish tricolor aside. World War I led to two cancellations of the parade; icy streets and snow stopped the event in 1920, 1956, 1978, and 1993.

Man-made controversies have also dogged the near-annual event. It is worth remembering, however, that what so many take for granted with regard to the parade was not ever so—even in recent years.

In the Beginning

For the Boston Irish, honoring – let alone celebrating – St. Patrick proved a long struggle. The first local stirrings to commemorate Ireland’s patron saint came in 1737. On March 17 of that year, 26 men – the Charitable Irish Society – gathered in the heart of the Puritan city to hold a decidedly Improper Bostonian event. (There is evidence suggesting that the Charitable Irish held the first Saint Patrick’s Day Parade a dozen years earlier, in 1724.)Perhaps the best-known Boston Irish symbol of the holiday is The Parade. Locally, the phrase means one thing – South Boston’s annual St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

It all started officially in 1901, but the procession that so many both enjoy and take for granted today did not get scheduled easily. After Irish-Catholic immigrants began landing here in ever-increasing numbers in the 1840s and 1850s and staked their claims to new lives in America, they soon were thumbing their collective nose at Yankee antipathy to any commemorations of St. Patrick’s Day.

As early as 1841, without official sanction by government officials, more than 2,000 local Irish, after honoring their patron saint at a traditional Mass, had marched through the North End, their bands booming, their crowds singing.

By 1900, St. Patrick’s Day parades organized by the Ancient Order of Hibernians, which numbered some 8,000 members in Boston alone, had become the norm. Bands, organizations, refreshments – all were handled by the Hibernians’ Entertainment Committee.

In mid-March 1901, the blare of bands and the vibrations of marchers’ feet pealed above South Boston’s streets. Banners awash with glittering shamrocks, harps, and images of the patron saint himself nodded in the gusts racing in from the Atlantic. The date, however, was March 18 – with good reason. The city’s leaders had sanctioned South Boston’s first official St. Patrick’s/Evacuation Day Parade for the 18th because the 17th had fallen on Sunday and was subject to the Blue Laws. On that Monday morning, the procession commenced with Major George F. H. Murray the inaugural chief marshall for the parade in 1901.

In a nod to the burgeoning political power of the Boston Irish, the City of Boston served as the parade’s sponsor until 1947, when Mayor James Michael Curley –“Himself” – found a way to make the event even “greener.” He designated the South Boston Allied War Veterans Council as organizer, planner, and sponsor of the parade – and as arbiter of who got to march in it. The seeds of future political, social, and cultural strife had been sown and would erupt in later years on the literal and figurative route of the procession.

‘The Troubles’ Come to the Parade

Some 25 years later, as “The Troubles” raged in Northern Ireland, many of the Boston Irish espoused their support of the Irish Republican Army, most notably in the form of the local chapter of the Irish Northern Aid Committee. Irish nationalists marched in an unofficial manner in a number of the South Boston St. Patrick’s Parades, but in 1972, the nationalists’ presence took a blatantly public turn. Representatives of the Northern Aid group marched with a coffin shrouded by the Irish Tricolor and held a sign proclaiming “England, Get Out of Ireland!” They all wore black armbands.

The March 20, 1972, Boston Globe ran a quote by Jim Dunn, of the Irish Republican Aid Committee: “This is the sort of procession that should be taking place today. We don’t think bands should be playing and people cheering while people are dying in Belfast and Derry.’’

Race and the Parade Route

With racial tensions rising in Boston (the school desegregation/busing era), Massachusetts, and the entire nation in the 1960s and 1970s, the unrest seeped into and eventually exploded over the parade. In 1964, the NAACP decided to enter a float in the march, knowing how risky the gambit was but wanting to appeal to a perceived bond among Black people and the local Irish for social equality. On March 17, 1964, NAACP Executive Secretary Thomas I. Atkins explained to the Globe, “The purpose of our entry… and the message of the sign re the same — the basic similarity between the Irish fight for freedom and the freedom fight of the Negro for equality.”

A number of parade watchers proved anything but welcoming. Rocks, bottles, and racial epithets poured down on the organization’s float from an element that the NAACP. deemed the “lunatic fringe.”

Racial turmoil continued to beleaguer the parade through the busing crisis of the 1970s. With the controversial measure igniting rage in white and Black neighborhoods, tensions erupted at the 1974 parade, where Boston Mayor Kevin White was jeered and pelted with snowballs.

A year later, anti-busing floats elicited loud cheers. So high did tensions soar that in 1976, US Army Col. Forest Rittgers of Fort Devens declined to allow his units to March in the parade because his troops had endured volleys of hurled snowballs, firecrackers, and racist insults in the 1975 parade, according to the Globe. Even though 1976 was the 75th anniversary of the parade, the busing crisis reduced the usual throng to roughly half the event’s usual numbers.

A Long Slog toward Equality

In 1992, the South Boston Allied War Veterans Council denied the application of the Irish American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, or GLIB, to march in that year’s parade. GLIB, winning a court order to march, did so. In 1994, when GLIB filed and won a sexual-discrimination suit against the parade’s organizers, the Allied War Veterans responded by canceling the parade.

Eventually, the case wound its way to the US Supreme Court. In 1995, the justices ruled that the Allied War Veterans Council’s right to free speech on religious grounds – their Roman Catholic faith – gave them the green light to ban gays from marching.

Time, like the parade, marched on. Over the ensuing 20 years, gay activists fought for the right to join the parade, with gay veterans leading the way. In March 2015, Boston Pride and Outvets were allowed to join the procession, and in response, Marty Walsh became the first Boston mayor to march in the parade in some two decades.

“With this year's parade,” he told the media, “Boston is putting years of controversy behind us.”

For further reading, see the book “South Boston on Parade,” by Paul Christian.