By Larry Donnelly

Special to Boston Irish

WICKLOW, Ireland – There have been a lot of strange sights in Ireland since the outbreak of Covid-19. In the early days of March, April, and May, perhaps the most outstanding one was school-aged children running around on the streets on weekday mornings. And their parents, many of whom were desperately trying to do their jobs from home, spent too much time chasing them forlornly and shouting “social distance!”

I was among the defeated soldiers and was positively delighted to leave my seven-year-old son, Larry Óg, at the school gate a couple of weeks ago. He was less pleased. For all sorts of reasons, I and other parents pray the schools can stay open.

Another particularly odd vista has been the darkened pubs throughout urban and rural Ireland. Until the 29th of June, all venues with licenses to sell alcohol and food on the premises were locked up tight. From that date onward, restaurants and pubs that offer food were allowed to open and to sell alcohol, so long as a meal costing at least 9 euro was purchased, social distancing measures were strictly implemented, and patrons stayed in situ for no longer than 105 minutes.

Here in Wicklow Town, which is something of a microcosm of small-to mid-sized towns in Ireland, two gastro-pubs, The Brass Fox and The Bridge Tavern, re-opened in late June. Local residents who can afford to do so, as well as visitors from other parts of the country, have made a concerted effort to support these important businesses. Yet their trade has been down appreciably from what they would ordinarily anticipate in high summer with foreign tourists milling around.

Meanwhile, those of us who are members of Wicklow Golf Club have been able to enjoy food and drink in the comfort and safety of the clubhouse with stunning views from a cliff top above the Irish Sea.

In the past three months, the horrible term “wet pub” – rated by Irish people as one of the most annoying new expressions to emerge from the current period of crisis, together with what they regard as an awful Americanism: “staycation” – has been applied to pubs that do not serve food, hence remained shuttered. Many have asked what possible distinction can be drawn between them and pubs that have kitchens.

An independent Kerry TD, Michael Healy-Rae, put the question starkly to the government: “What is the difference between a person inside a public house with a pint of Guinness in this hand and a toasted cheese sandwich in this hand and a person inside another pub with a pint of Guinness and no toasted cheese sandwich?”

His is a cogent point and is amplified by the financial struggles faced by those who own or work at small, often rural pubs that have been forbidden from operating since mid-March. It has been disheartening every time to pass by my own local pub in Wicklow, Fitzpatrick’s, and read the unchanged sign in the window: “Closed from 7 PM on 15th March.” But in response, expert officials repeatedly assert that the virus loves alcohol and how it lowers peoples’ inhibitions when it comes to close physical contact and claim that this sacrifice has been absolutely necessary in the name of public health.

And some scoff at the notion that there should have been any rush to prioritize pubs in light of Ireland’s well-documented relationship with alcohol that is accurately described as unhealthy. This is a valid observation to an extent, yet it overlooks the unique role Irish pubs play in the countryside and in the cities, where they are typically community hubs to which young and old gather more for company and conversation than for drink. Indeed, the vital function that the pub continues to play in Irish society has helped make it an institution duplicated around the world.

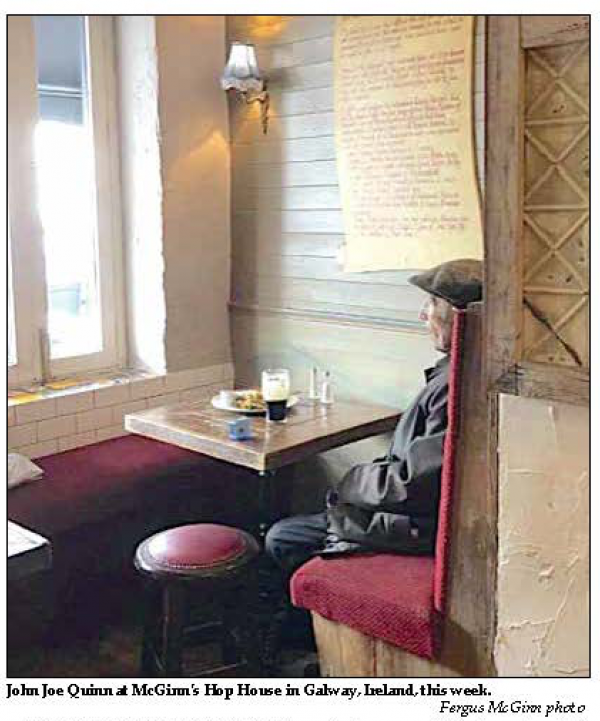

Much of this was encapsulated recently in a photo taken in a Galway pub of an elderly gentleman on his own with a plate of finished food and a half-consumed pint of Guinness in front of him. The man also had a clock on the table.

The picture was taken by a good pal of mine, Fergus McGinn. Fergus is well known among the Boston Irish both for having previously been the proprietor of two popular Galway establishments – Richardson’s of Eyre Square and Monroe’s in the city’s rebranded “west end” – and for having many friends in Massachusetts’s sizable community of emigrants and further removed descendants from the west of Ireland.

Insofar as it captured the poignancy of an old man by himself and the unfortunate realities for many of living in isolation during a global pandemic, it is no surprise that the photo went viral and was ultimately the subject of an article in the New York Times. The story behind the photo was, as usual, more complicated. The man in it, John Joe Quinn, had brought the clock in order to ensure he would get home on schedule for the 6.1 evening news on RTÉ. Contrary to some claims, John Joe did give his approval for the photo to be taken and shared on social media and got a kick out of becoming an internet sensation.

The photo portrayed an undeniable truth about Irish pubs, however. As Fergus McGinn said subsequently about his eponymous establishment tucked in the relatively quiet Woodquay section of bustling Galway City: “Most of our customers here would be retired. Men of that generation used pubs for socializing. It’s not like now when people use their phones to socialize. Take that away and what are they left with?” Precious little, I’m afraid, is the answer. And it’s not older men alone who would be bereft.

Here’s hoping that as many Irish pubs weather this brutal storm as possible. I am a big fan of going to the pub. And I know plenty of people back in Boston – both those who love their pints and others who aren’t especially interested in drinking – who agree completely. For most of them, invariably entertaining visits to welcoming watering holes are a cherished aspect of their trips to Ireland.

Coronavirus has had countless devastating consequences. To be fair, hastening the decline of Irish pub culture is far from the worst of them. But it’s still sad to see.

Larry Donnelly, a Boston born attorney, has lived in Ireland since 2001 and is a Law Lecturer at the National University of Ireland, Galway. He is also a regular media contributor on politics, current affairs and law in Ireland and the US. Follow him on Twitter: @LarryPDonnelly.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sidebar- An image of a time receding

The limit is 90 minutes. You can only stay in the pub for 90 minutes. If a single photo can capture the zeitgeist of a nation, [see above on this page], this might be it. It caused a lump in my throat and for a wide variety of reasons, wrote Brian O’Donovan on Facebook recently.

“This is from a pub in Galway taken last week, and has already gone viral, so you might see it in lots of places,” he wrote. “Subsequently, after becoming famous on the 'net, the man involved said that he always brings the clock with him to get home for the evening news, but it is easy to see why this photo initially caught the imagination.

“In Ireland, only pubs that serve food can be open. Because of Covid, there is a 90-minute time limit per customer. This man is from a different world, it seems.

“I'm 63 and consciously avoid the use of words like old, older, or elderly. This man with the cap is probably not that much older than me, but everything about this scene is from a different era, what I call the "old Ireland." A time receding.

“There is a gentility to it. A rhythm. A serenity bordering on insouciance, and yet, his quiet acquiescence to the reality of pandemic life today in Galway.

“The food has been dutifully ordered but barely picked at. Food is not the reason he is there. The pint is being savored. The solitary position, deliberately chosen. But it is the little alarm clock, the one this very morning that was next to his bed, and will be again tonight. No iPhones here. No Apple watches. This is his way of timing what should never be timed, WAS never in Irish history timed before. The delicious, contemplative, lost-in-thought, late-afternoon-ticking-clock consumption of a couple of pints in a quiet pub in this City of the Tribes. 90 minutes.

“The man is 'sitting in the wizen daylight....' and my own thoughts are of passings, and ghosts, and mortality 'as shadows vanish....through archways of forgotten Spain.'