April 27, 2020

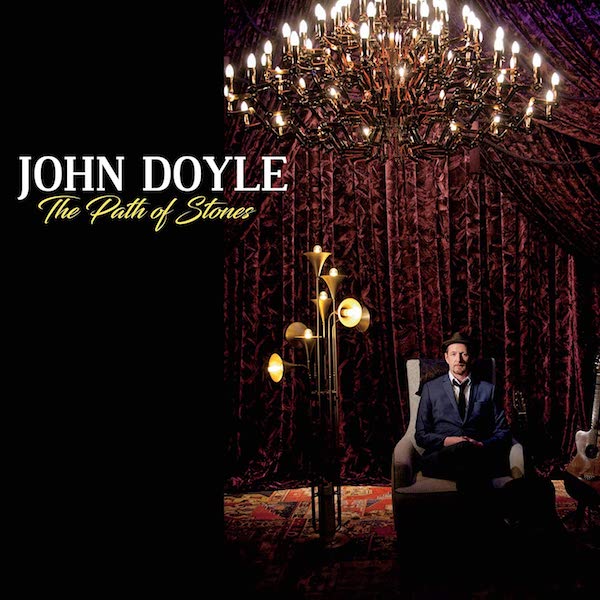

John Doyle, “The Path of Stones” • The burden of being so good at your craft is that you’re in such demand, you don’t always have time to do something just for you. Which may help explain why John Doyle, a consummate talent in Irish/Celtic music for the better part of three decades, has only now released his third solo album – and first since “Shadow and Light” in 2011. Given his collaborations with Solas, Liz Carroll, The Alt, Joan Baez, Usher’s Island, The Teetotallers, Karan Casey, Ashley Davis, and many others over the years, though, it’s perfectly understandable.

It was on “Shadow and Light” that Doyle formally unveiled his talents as a songwriter, and he’s only gotten better in the interim. His songs evince the language, imagery and structure, as well as subject matter, associated with folk and literary traditions, but they don’t come across as pale imitations of the form – there’s an integrity and richness to them. They are given an additional gloss by Doyle’s understated but resolute vocals, combined with his trademark guitar brilliance (Doyle also plays mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, fiddle, harmonium, and bodhran).

As a benchmark of sorts, Doyle starts off this album with a slightly revamped version of the classic 1798 ballad “The Rambler from Clare,” marrying the traditional words to his melody. It’s as rollicking and rakish as ever, spiced by Rick Epping’s harmonica and Duncan Wickel’s fiddle, and reminds us of the delights to be found in Irish folk song tradition – a standard that Doyle is more than able to meet.

The album’s title track provides a fine example of the influences and inspirations on Doyle’s palette. Commissioned to write a song based on a Yeats poem, Doyle passed on the more obvious and well-known options (“Lake Isle of Innisfree,” “Leda and the Swan,” “The Falling of the Leaves” et al) in favor of “He Mourns for the Change That Has Come Over Him and His Beloved and Longs for the End of the World” – from which, as it happened, he only used snippets, along with fragments from the song attributed to the ancient bard Amergin Glúingel. The result is a brooding but vivid meditation on love, loss and memory:

I have walked on the path of stones

The wood of thorn surround me

At night the lonesome call of owl

At dawn the cockerel crowing

And I’ve lost love and I’ve lost again

No scar could prove deeper

In a similar vein is “Lady Wynde.” The title character serves as a metaphor for not only the spirit of the wind but also “the spirit of freedom,” Doyle explains in his notes – something that, however much we may seek, we often “fear when it finds us.” What would’ve been a quite lovely song – flavored with references to landmarks in his ancestral South Sligo – with just Doyle’s voice and guitar becomes all the more exquisite with harmony vocals from Dervish lead singer Cathy Jordan and Wickel’s gorgeous fiddle and cello.

Lady Wynde, lady wanderer restless and free

No man can claim you no one holds the key

Where do you go to, what do you find

When all the world beckons, where are you Lady Wynde

By contrast, “Teelin Harbour” is a storm-tossed portrait in relentless 6/8 of curraghmen off the coast of Donegal braving the elements as they fish for herring. The lyrics are hybrid English-Irish, in a call-and-response format that recalls older Gaelic sea-faring or waulking songs; Jordan joins Doyle on the refrain a couple of verses in, further enlivening the narrative, as does her bodhran playing and the addition of John McCusker’s fiddle to that of Doyle.

Doyle’s knack for historical-based songwriting, one of the many virtues of “Shadow and Light,” is less in evidence on “Path of Stones” but still well represented with “Her Long Hair Flowing Down,” a love song filtered through the experiences of a 19th-century Irish exile seeking redemption in the California Gold Rush.

In addition to Jordan, Wickel, McCusker, and Epping, Doyle’s supporting cast includes flute wizard Mike McGoldrick, who joins Doyle on “Elevenses” – the first of four instrumental tracks that also feature Doyle originals. “Elevenses” begins with the emblematic Doyle rhythmic stroke and his ever-agile flat-picking; shortly thereafter, McGoldrick enters, matching him note for accented note, and just when it seems the track can’t get any better, it does.

Doyle closes out the album with an air, “Knock A Chroí,” followed by a jig, “Beltra Fair,” and a slip jig, “Aughris Head,” with him playing all the instruments – three different forms of guitars, plus bouzouki and keyboards. By then, you’re already counting the days – and hoping there won’t be too many – until the next solo Doyle release. [johndoylemusic.com]

JigJam, “Phoenix” • It’s pretty much unavoidable: Talk about JigJam, and sooner or later you mention We Banjo 3. So let’s get that part over with. Both bands – both of them quartets – are arguably the most high-profile proponents of what’s known as “Celtgrass” or “I-Grass,” a banjo-focused fusion of Irish folk and traditional music with bluegrass and American folk/roots styles; “newgrass” – bluegrass with rock/pop flavorings, plus jazzier chord progressions and voicings – is a key facet as well. The members of JigJam and WB3 alike have solid backgrounds in Irish music, with plenty of Fleadh Cheoil successes, but are equally convincing on the Americana side. The two groups, who got their starts in the early 2010s, also have followed a similar trajectory in their increased emphasis on original material and songwriting.

JigJam’s instrumentation is somewhat more diverse and extended, adding dobro, double bass, harmonica, and bouzouki to fiddle, guitar, mandolin, and banjo (tenor and five-string). But the essential sound and vibe is much the same as WB3: energetic, up-tempo instrumental passages with rousing fiddle, mandolin, banjo, and dobro solos; shifting rhythms and time signatures within a song (such as on the opening track, “Someday”); and soaring vocals – more polished and pop-ready, less of the “high lonesome” quality – in this case from lead singer Jamie McKeogh, with Daithí Melia (five-string banjo, dobro, guitar) and Cathal Guinan (bass, fiddle) in support, plus Gavin Strappe on mandolin and tenor banjo.

(By the way, there’s no evident rivalry between JigJam and WB3. They’ve spoken highly of one another, and have shared the stage on several occasions; you can see and hear the results for yourself on YouTube.)

Having two of almost-if-not-quite the same thing, however, is not bad in and of itself, right? This is infectious stuff – I know, “infectious” is maybe not the adjective to use nowadays – that just feels good to listen to: the guitar/fiddle duet between McKeogh and Guinan at the beginning of “Red Paddy on the Ridge” – a rare excursion into the purely Irish part of JigJam, with a medley of reels “Rakish Paddy” and “Flowers of Red Hill”; “June Apple,” a traditional American song through which the band showcases its essential blue/newgrass character; “Big Grey Dog,” a road movie of the band’s misadventures traveling from Las Vegas to Indianapolis, animated by a jaunty call-response chorus and a comic, climactic passage in 3/4 time.

McKeogh’s “Tullamore to Boston,” which closes out the album, is an expression of civic pride for their home and a paean to Daniel E. Williams, whose initials are immortalized in the whiskey he made famous through the old Tullamore Distillery. (Boston, incidentally, is simply a reference point in the chorus, rather than integral part of the song.) “The Dew” may or may not suit your taste, but there’s deliciousness in the irony of four Irish fellas singing its praises using a music form that, while derived from Irish tradition, has emerged as a distinctly American genre – one which JigJam has mastered. Same again, please. [jigjam.ie]