December 4, 2019

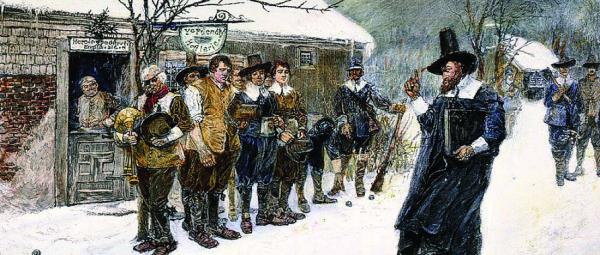

Long before the immigrant Irish Catholics swelled Bost0n’s population in the mid-1800s, the Puritans had made clear that Christmas Day was an odious happening. This artwork relates to 1659, when the General Court of Massachusetts Bay Colony passed a law setting a five-shilling fine from anyone caught "observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way." The law was repealed in 1681, and it was not until 1856 that Christmas Day became a state holiday in Massachusetts.

Artwork courtesy of Mass Humanities and its Mass Moments series.

BY PETER F. STEVENS

BIR STAFF

From 1800 to 1850, Irish immigrants could scarcely have picked a worse place than Boston to celebrate Christmas. The Puritans loathed “Popish” Yuletide rituals so much that, in 1659, the Massachusetts General Court had enacted laws against honoring the day. Anyone caught toasting the occasion suffered a five-shilling fine.

Above all, for the Mathers and other Puritan luminaries, Christmas celebrations symbolized “Papists” and their church.

In such a climate, Boston’s Irish celebrated the holiday in muted fashion until their political clout swelled in the late 1800s. On the “old sod,” the holiday had largely revolved around Mass and family, not the raucous celebrations of any feverish Puritan and Yankee imaginations, so the early Irish of Boston noted the holiday simply, with many families keeping children home from schools later in the century.

At St. Augustine’s, in South Boston, and later at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, Christmas Masses were held in the opening decades of the nineteenth century, always under suspicion by the local Yankees. As German Catholic immigrants arrived and began attending the local “Irish churches,” the newcomers introduced locals to Christmas trees and greeting cards; a thaw in the region’s traditional, Puritan-steeped Christmas notions was slowly emerging.

The Christmas season of 1887 brought a “holiday” card that inflamed Irish from Dublin to Boston. Issued by Angus Thomas and entitled “Ode to the Specials (police),” the card belittled the largely Irish crowd that had gathered at Trafalgar Square on Nov.13, 1887, to protest the imprisonment of Irish MP William O’Brien. Thrown in jail for having orchestrated riots against landlords, O’Brien had become a hero to his countrymen in both Ireland and Boston not only for his stand against the rent collectors and their agents, but also for his refusal to wear prison clothing and his campaign to wrangle political prisoner status for fellow Irishmen in British cells.

On Sun., Nov. 13, 1887, a throng defying Commissioner of Police Sir Charles Warren’s ban on open-air meetings assembled at Trafalgar “to demand the release of William O’Brien, MP.” Constables, foot guards and life guards waded into the crowd to clear the square. No shots were fired, but fists, feet, and clubs killed two people. The protestors’ phrase described the tragedy, a term to chill the Irish again and again: “Bloody Sunday.”

Shortly after the melee, Angus Thomas released his vitriolic card, hardly a subject to foster “peace and goodwill to all men.” His “Christmas” theme featured not the images of St. Nick or a Nativity scene, but a club—a police truncheon. His idea of humor was the following lines about the weapon swung against O’Brien’s supporters: “To be used with great care.”

For the Irish at home or abroad, the card’s Yuletide sentiments were appalling:

Ode to the Specials

In Trafalgar Bay where the French men lay,

A Hero was Nelson there!

But nothing was he tho’

King of the Sea.

To the Kings of Trafalgar Square.

With Jack on Watch and with battened hatch.

There France in the pride was quashed.

Washed in the waves where they found a grave—

But they batton’d “The Great Unwashed!”

Then surely the fame of Nelson’s name

The Specials have right to share:

He won the day in Trafalgar Bay

But They in Trafalgar Square

With Best Wishes for a Specially Jolly Christmas

By the time of 1887’s “Bloody Sunday,” Boston’s Irish were a genuine community, slowly amassing clout at the ballot box and bucking Yankee strangleholds on business and the courts. If any in the Irish wards ever needed a reminder that as hard as life in Brahmin Boston could be, their countrymen overseas still faced greater obstacles, the Bloody Sunday “Christmas Card” was vivid proof.

Thankfully, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, Boston’s Irish could celebrate Christmas as openly as they wanted, with family parties and dinners, church socials and midnight Mass turning the Yuletide season into a genuine holiday.

As Thomas H. O’Connor writes in Boston Catholics, “Boston Catholics participated in a perpetual calendar of familiar religious devotions that…bound them more firmly together as members of their own distinctive parishes.”

During the period of Advent in late November and early December, for example, persons of all ages prepared for the coming of the Christmas season by attending daily Mass. They then enjoyed the celebration of midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, often followed by festive and early morning breakfasts with friends and relatives.

Those scenes would have been virtually unthinkable for Boston’s earliest Irish immigrants. Yet by the turn of the twentieth century, the Irish openly celebrated the Yuletide as cheerfully as they pleased in the city where Puritans had once banned the holiday and had punished transgressors with fines or the stocks.

Through religion, reflection and revelry, Boston’s Irish could finally celebrate Christmas in “grand fashion.”