November 1, 2017

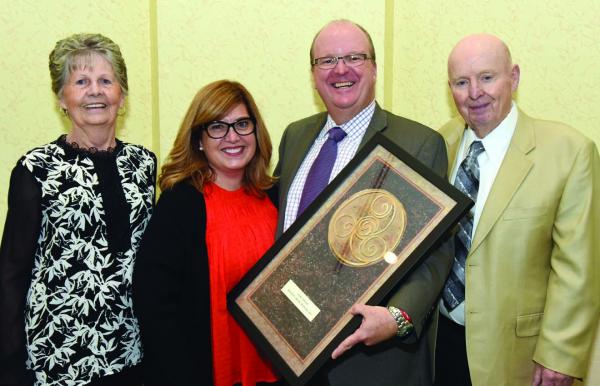

A proud son of Southie, Tom Tinlin

personifies the virtue of public service

There was a time — before his life was nearly cut short by an undiagnosed brain aneurysm — when Tom Tinlin was best known in government circles as the consummate Mr. Fix-It. First— and most notably— for Mayor Tom Menino, as he rose from a security officer working the front desk to the city’s transportation chief in the span of a decade. After that, briefly for Deval Patrick, and finally for Charlie Baker, Tommy Tinlin was the versatile, witty, and unflappable lieutenant, the cabinet chief who could be counted on to give you a straight answer and a sensible solution.

When his mug would show up on your TV screen under a hard hat and over a fluorescent MEMA vest, it usually meant some natural calamity was under way.

“Tommy has always been in the news,” says Heather (Canavan) Tinlin, his wife of a quarter-century. “If you saw him, you knew it was time to go get milk and bread.”

Tommy Tinlin was — and is— the urban mechanic’s urban mechanic. All of that changed suddenly last April when the thunderbolt struck. While the 51-year-old Massachusetts Highway commissioner was emceeing a charity event for South Boston’s Fourth Presbyterian Church, the excruciating, week-long headache he’d been nursing with pain meds and sleeping pills suddenly turned violent. He nearly blacked out, then walked off the stage, turned to Heather, and uncharacteristically demanded: “Take me to the hospital. Now!”

After emergency surgery and 12 days in the hospital, Tom Tinlin had survived his brush with death, which was chronicled brilliantly in a Boston Globe feature by Nestor Ramos last August.

“Heather saved my life long before that ride to Beth Israel-Deaconess. She’s the most special person I’ve ever met,” he told the Reporter recently in an interview. “I’m blown away that she wants to spend the rest of my life with me.”

What happened to Tom and Heather and their children, Thomas, 17, and Grace, 15 (as Tinlin was quick to note, this was a crisis for his whole family) was preventable. A CAT scan — had his physician ordered one — would have detected the ticking time bomb in his head. Now, working in tandem with the Brain Aneurysm Foundation, the Tinlins are devoted to spreading awareness about the warning signs to the public and the medical community.

“We can educate the public, but if doctors aren’t asking the right questions and doing the tests, all the education on the public side is for naught,” Tinlin says. “It has to be something that professionals are talking about. If my doctor listened to me— if my doctor did right thing— Heather would not have left the hospital that day wondering if I was going to survive or not.”

An early riser from the very start

Thomas Jude Tinlin made his debut at a different hospital— St. Margaret’s— on May 26, 1965. He was born earlier than expected, the baby brother of Kelly and Kerry and only son of Tom Tinlin and his bride, Anne (Madden) Tinlin, a couple minted in Southie’s Old Colony projects. They were married at St. Augustine’s in 1961 and nurtured their young crew in a flat on Second Street. Tom Tinlin, an Air Force veteran, hauled Schlitz kegs — and later Buds— across greater Boston as a proud union truck driver. Their kids learned their work ethic from both parents. Mom took a part-time job making beds at the Bay View Nursing Home on P Street. Dad missed the start of his own “retirement” party from the Teamsters because he’d decided to start a new gig: managing beer concessions at Fenway Park. He’s still on the job — and loving it— at age 78.

“I remember one time — I was 10 years old— and my dad came home with a cast on his hand,” says Tom the younger. “He’d broken it at work the day before. He went right into the bathroom and soaked the plaster in the tub so he could take it off himself. We couldn’t afford to have him out of work.”

There are a few clans that claim deep roots in Southie, but the Tinlins have the town in a strangle hold.

Thomas McMahon, Tommy’s maternal great-great grandfather, emigrated from County Clare in 1874. He met his wife Eleanor— also from Clare— and moved into a flat on W. Fourth Street. They packed the joint with seven kids, including Tommy’s great-grandfather, Patrick Joseph McMahon, who married a “girl from the ice” —Catherine. They staked their own claim, settling at 392 W. Fourth St.

Their daughter— Tommy’s grandmother, Louise McMahon— met and married John Tinlin, who served in the Coast Guard during WWII and later split from his wife and family. Louise single-handedly raised her brood of seven kids — including Tommy’s dad, Thomas J. Tinlin—on Darius Court in the Old Colony development. Louise found work at the old Carney Hospital on Telegraph Hill, now operating as Marian Manor. When the Carney decamped for greener pastures in leafy Dorchester, Louise followed and eventually found her own apartment in a three-decker near the hospital campus.

While still in “the bricks”— Tom Tinlin’s dad met and courted his mom, Anne Madden, a sweetheart from Patterson Way. Their first-born was Kelly, who later married Coley Nee, another stalwart Southie clan of Connemara extraction. She became a powerhouse in city law enforcement and rose to the rank of deputy superintendent in the Boston Police Department before “retiring” last year to become the first chief of the Boston University Police. Second daughter Kerry— the family’s resident “adrenaline junkie”— is a nurse and consummate first-responder, making regular airborne runs as part of a MedFlight units out of Cape Cod Hospital and Milford Regional Medical Center.

From street corners to Gillette and City Hall

The baby of the bunch, our subject, chugged along predictably at first— grammar school at St. Brigid’s and high school at Christopher Columbus in the North End, where the Italian lunch mothers spoiled students with pasta and “gravy.” Tommy Tinlin’s teen years were spent on Southie street corners and, later, at the L Street Tavern before it was a Robin Williams sound stage. College was an option, but not a pressing one, nor his first choice, by a long shot.

“My biggest ambition was to make 10 bucks an hour,” recalls Tinlin, who made short work of that bucket list item by pulling the 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift in the “hot room” at the Gillette factory. The magic of molding plastic razors on the piers of the Fort Point Channel wore off after a few months. In 1987, a neighborhood sponsor, Eddie Wallace, tucked him into a security guard’s seat at Ray Flynn’s City Hall at age 22.

It was a life-changing moment.

First, and most importantly, it was there that Tom crossed paths with Heather Canavan of K and Fifth, and two years his junior. He was immediately smitten with the young mayoral intern, whom he somehow had never met in his Southie travels. “She was funny, pretty, and had no use for me at all,” says Tom with a laugh. “But I was going to wear her down one way or another.”

Says Heather: “We had all these things in common.” Friendship turned to flirtation and, after Heather graduated from college, romance. They were married in 1992 and celebrated their 25th anniversary this month.

The newlywed Tom Tinlin had been giving some thought to becoming a Boston cop, but he wasn’t all that sure of his long-term plans. But City Hall serendipity was not done with him yet: He had just met an Italian guy from the western reaches of the city who would change his life.

For some reason— and no one really fully grasps why— Tom Menino took a shine to the red-faced kid from Southie. The Hyde Park district councillor, who had recently earned his own long-deferred college degree at UMass Boston, leaned on Tinlin to do the same.

“We used to say that the mayor could see around corners, for people and situations,” says Michael Kineavy, another Southie kid from Second Street who became Tom Menino’s closest City Hall aide. “If you had walked by [Tinlin] at the security desk, you wouldn’t have known he had all this capacity. He saw something in Tom early on. I think he probably saw that he has a good heart.”

When Menino was elevated to interim mayor after Ray Flynn left for the Vatican, Tinlin was one of the few loyalists he could count on in South Boston, where Dorchester state Rep. Jim Brett was the local favorite in the 1993 race to pick a full-term successor.

Peter Welch, Menino’s chief of staff, enlisted Tinlin to organize a “time” at the South Boston Yacht Club. “We got a call that the mayor was ten minutes out and the place was pretty much empty. “All of a sudden— swoosh— there are people swarming in. We had a full house in Southie for him that night. He was pretty pleased.”

Tinlin’s loyalty and hustle paid off within hours of Menino’s November election victory. The next morning, he was summoned to the mayor’s fifth floor perch overlooking Faneuil Hall. Menino wanted Tinlin to be his full-time Southie sentry in the Office of Neighborhood Services.

“He said, ‘I want you to come and work for me,’ Tinlin recalls. “But, he also said, ‘You have to promise me you’ll go back to school.’ ” It was not a request. “I would call it a mandate,” deadpanned Kineavy. “There were a couple of people the mayor really pushed in that way.”

Heather Tinlin was fully on board with the mayor. “Honestly, I was nagging Tommy to go to college, too. But the mayor saw him in all kinds of capacities, addressing some serious things that happened in security. He really saw something in him.”

Taking the mayor’s urgings to heart

After a false start or two, Tinlin found his niche at Eastern Nazarene College, where he enrolled in night classes. “Eastern Nazarene gave me the tools I needed. It taught me how to study again,” he says.

Within days of Tom’s getting his bachelor’s degree, Menino pulled him aside again.

“Congratulations,” he said. “Now guess who getting his master’s?”

Menino then plugged Tinlin into a slot in a city-sponsored graduate degree program at Suffolk University, where he earned a master’s in public administration over the next two years.

“I thought I was getting punished at first, that’s the kind of dope I am,” laughs Tinlin. “Suffolk made me a better employee and changed me as a manager.”

Those were important skills to have as he joined the inner circle of the Menino administration with a promotion to acting commissioner of the city’s Transportation Department. It was a demanding position in which Tinlin earned a reputation as a hands-on, no-nonsense manager who would personally respond to accidents or water main breaks in the middle of the night.

Menino, who died in 2015 from cancer, earned a reputation as a tough boss, but Tinlin says that any re-telling painting Menino as a bully is way off. “He was very direct. You got a full report card every day. But it was never personal,” he said.

Cabinet heads could expect the mayor to ask a simple question that was a hallmark of his leadership style: “Who are we helping by doing this?” Says Tinlin: “It had to begin and end with that. I don’t think he gets enough credit for how that sort of direct communication works. His intuitions were always so sound.”

Menino came to rely on Tinlin’s counsel, too, and not just on matters of transportation. He was the mayor’s guide for navigating the annual St. Patrick’s Day breakfast— the political roast that the mayor looked forward to about as much as he did a root canal.

“He wrote all the jokes - which the mayor always butchered but somehow made more hilarious,” recalls Dot Joyce, Menino’s longtime press secretary and confidante. “Tom Tinlin is the total package. We couldn’t have survived some difficult days without him.”

On the state stage, preaching an ‘urban sense of urgency’

Tinlin brought all of the lessons learned at Menino’s side to state government in 2013 when he joined the Patrick administration as the chief of operations for the state’s highway department. Patrick was winding up his term and Gov. Charlie Baker was in the wings.

“I thought I was going to the state for a year while I figured out what I wanted to do next,” says Tinlin, who first met Baker during his transition. “Immediately, I said, ‘This guy gets it.’ I wasn’t necessarily on his team, but he was deferring to me, asking all the right questions. And he wasn’t hesitant to get his hands dirty.”

Baker bought into Tinlin’s guiding principle: Adopt a Menino-like approach to the day-to-day workings of state government.

“I wanted to bring an urban sense of urgency to state government. As a former municipal official, there were times we thought that the state was out of touch with what the real needs of municipalities are. Governor Baker really gets that. He wanted to make sure we were doing everything we could do to help the cities and towns.”

Sometimes, that meant his Mass Highway chief showing up in person to far-flung parts of the state. Last winter, as Fall River’s rookie mayor struggled to deal with back-to-back blizzards that had emptied the city’s reserves, Tinlin showed up at his door— in person— to assist.

It wasn’t just these small acts of kindness that earned Tinlin plaudits for government service. On his watch, the state accelerated its bridge replacement program to make necessary fixes less disruptive and, in a bold move, dismantled the state’s longtime toll booths on the Mass Turnpike, replacing them with an all-electronic system.

Tinlin always encouraged his staff to come up with new ideas— a philosophy that doesn’t always bubble up in risk-averse bureaucracies. “In government, you have people who don’t want to see their name in the paper if something doesn’t work out. I told my people, ‘You don’t have to worry about it, because it’s my name, not yours, that’ll make the paper.’ I’m willing to embarrass myself for the sake of trying to do things more expeditiously.”

After his health scare last spring, Tinlin returned to work sooner than expected. But then he decided— to the surprise of many— to retire from state government. The pace and demands of the job— mixed with his own compulsive focus on showing up to everything— weren’t the best recipe for a continuing recovery.

In September, Tinlin joined the Boston engineering firm Howard Stein Hudson as the director of Institutional and Private Markets. Despite his departure from the scene, he speaks with affection for the people he met over the years of his work in government.

“I miss the tow truck drivers, the guys fixing the guardrail, working with people, traveling around the state and doing those things that have to get done,” he says. “I think to do what we do and do it well, you have to be wired a certain way. I miss the people.”

When it comes to Southie, passion drives the man

“The town has changed, but Tommy has kept the ingredients of the best of old South Boston and transported it to what it is today,” says Michael Kineavy. “He’s invested, he’s involved. He’s a family guy, a coach, he’s at all of the events. He’s a hybrid in the best possible way.”

Tinlin is more modest about this, naturally. But there’s no doubt that his devotion to Southie is heartfelt, even passionate. He’s instrumental, often behind the scenes, in everything from golf tournaments and charity events to the St. Patrick’s breakfast, now hosted by [my wife], state Sen. Linda Dorcena Forry, who counts Tinlin as one of her most trusted advisors.

“I do feel a devotion to the town, but I think that means different things to different people,” says Tinlin. “The media want to portray this town as something that we’re not. It’s that reputation that formed around busing, and it’s unfortunate, because that’s not who we are.

The best way you show support is you just do what you think is right. To me loyalty to the town means making sure we are welcoming to everyone. You conduct yourself in such a way that you’d want your own family to be treated. We’re a neighborhood of immigrants. Everyone has had their first day in this neighborhood.”

For all that, Heather and Tom almost didn’t stay in Southie. As their family grew to four, they looked around for a house in the neighborhood, an increasingly frustrating search these days. They even peeked at an option or two in Dorchester, but they remained stymied until one day Tom got a call from a realtor who’d heard about a possible house for sale on E. 5th Street. It had a backyard.

The woman selling it — Barbara Logue—was an empty-nester and adamant that the next buyer be a neighborhood family. “I don’t want it in the Globe,” she said. “I want it to go to a Southie guy with kids who want to stay here.”

Tinlin went over to meet her. “Who are you to Louise Tinlin?” she asked, good-naturedly. “She’s my grandmother!” he replied.

It turned out that Louise and Barbara had worked together for years back in the day at the old Marian Manor and the Carney, and Mrs. Logue remembered her friend warmly.

“We talked for about 15 minutes, she named her price, I said, ‘Great, it’s a deal!” says Tinlin, who still trades cards and calls with Barbara Logue. “She’s an amazing, special person.”

This summer, as he recovered from his illness, Tom received a note from her. She was praying for him. And, by the way, she said, she’d also survived an aneurysm.

“Brain aneurysm is the number one killer that nobody is talking about,” says Tinlin.

“One in fifty will have one. Many will live a long life and never know it, but the odds are that it’s going to kill them or leave them with a life-altering injury. So I decided that that’s going to be my cause.”

“I’ve had some important people give me opportunities I probably didn’t deserve.

I don’t know what they saw in me, but these folks gave me opportunities. You can be a good person, but if you’re not given an opportunity… a lot of good people just don’t get that break.”

Tom Tinlin has caught his share of breaks in life: amazing mentors who opened doors and ushered him in. A medical miracle. And a partner who is devoted to him in ways he’s still trying to comprehend.

“Every day I’m awed by Heather. She was cool under fire that day, but she cared for me every day after that, too. I’m a blessed guy in many ways.”