May 30, 2014

For almost exactly a quarter-century, Black 47 has made raucous, often provocative, sometimes outrageous, and always full-hearted music, a distinctive brand of Irish/Celtic rock mixed with hip-hop, jazz, and reggae and imbued with a zeal for social justice and history – and an equally robust spirit of pride, fu,n and mischief.

But in November, 25 years to the date of their first gig, the band will ring down the curtain. Among the stops on their final tour will be the Boston Irish Festival, June 6-7 at the Irish Cultural Centre of New England [see separate story], where they’ve frequently appeared over the years throughout the festival’s various incarnations.

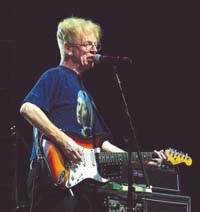

Kirwan

Kirwan

Recently, Black 47 co-founder, guitarist, lead vocalist, and songwriter Larry Kirwan shared his thoughts on the band’s legacy, their final album, “Last Call,” and a few more subjects, with Sean Smith of the Boston Irish Reporter.

Q. Any second thoughts or regrets within the band since announcing that this will be the last hurrah?

LK. I don’t think so. Of course, I can only speak for myself. But I reckon you make a big decision and then you go for it. Second-guessing life is no life.

Q. Do people seem to be accepting of your decision? Are you getting “How could you do this to me?” type of responses?

LK. There’s a lot of regret from fans, but that’s understandable. To some people we were the sound track to their lives, and to others it’s “I’ve just found you and now you’re finishing?” But we’ve always done things our way, so you can’t change with the last big decision. Because of the politics and social commentary, I’m very aware that Black 47 has been more than just a band to many, so I really want to finish the whole thing up in a dignified, complete, and principled manner.

Q. In explaining the band’s decision to retire, you’ve talked about “finishing up at the top of our game” and “going out on our terms.” Were there any subtle signs and portents suggesting that, perhaps, the energy or focus wasn’t as strong as it had been – and so maybe it was time to seriously consider ending the band before things began to seriously degrade?

LK. Not in the least. Had there been any of those “sign or portents” we’d have chucked it in long ago. It takes a lot of energy and commitment to actually keep a band going, so you need to be enjoying yourself and creatively moving forward on an ongoing basis. I thought we were sounding perhaps better than we ever did, and that was the real impetus. But also to wrap it up on a high note – we’ve made 14 or 15 CDs, and played perhaps 2,500 gigs. So why not put a cap on it so people can see Black 47 as a finite thing, not a combo going through an endless end but a creative entity that’s going out as it came in – with a bang.

Q. Inevitably, when a band announces it’s going to retire, people immediately start speculating about whether there’ll be a reunion. So, do you foresee that happening, and what circumstances would it take? Or, at least, might there be some collaborations among a few members, as opposed to the band as a whole?

LK. This is it – finito! What’s the point in a reunion? We’re a band for our times and I don’t want to look back. We have an album of all-new challenging songs; we don’t want to be an oldies group playing out the fans’ favorite requests. But we’re also finishing up as brothers. Of course, we’ll sit in with each other or play on each other’s projects but, as far as I know, there are no plans for that so far – and I definitely don’t have any. On the other hand, I’ve played with Thomas Hamlin (drummer) and Fred Parcells (trombone) since the early ’80s, so if I wanted a kick-ass drummer or a virtuoso bone player, I wouldn’t go looking on Craigslist.

Q. You’d already decided to retire before you started to record “Last Call.” Did that create a certain amount of pressure, to make the “perfect” ending artistic statement, and so on?

LK. No, that idea would be just a waste of time. Albums are about songs – and unless you’re talking about “Iraq” or “New York Town” (about 9/11), you’re dealing with 12 or 13 songs that you’re trying to string together in some meaningful way. I hadn’t written for the band in a couple of years. When we decided to make “Last Call” the songs just streamed out. I think I wrote eight of them in about three weeks. I’ve always been prolific but it surprised me. I guess that’s more and more the way I write: Find a vein, spike in, and write until I’m exhausted.

Q. How did you decide on “Hard Times,” by Stephen Foster, as the ending track?

LK. I had written a musical called “Hard Times,” about the life of Stephen Foster and the times he lived in. I took a body of his songs and re-imagined them, mostly by shaking off all the dust and calcification that had grown around them. Often while doing so I’d be struck by the way Black 47 could interpret those songs. “Hard Times,” in particular, seemed fertile material – mostly because I rarely liked the mournful way it has been interpreted. To me that song feels as if it needs an element of defiance or else it’s likely to sink under a wave of self-pity. And who better for defiance than Black 47! It did feel like a good way to finish Black 47’s recording career.

Q. In the online song-story notes, and in your blog, you talk about the less-appreciated, less-known aspects of Stephen Foster’s life and work – notably how impressed he was by the ethnic diversity in the music and dance of Five Points. This seems like a recurring theme in Black 47: taking a historical figure or event that has become obscured by the mists of sentimentality or other rose-colored emotions, and putting them in a new light.

LK. One of the good things about finishing up Black 47 is that, for the first time, I’m not under pressure to come up with something new. I realized that part of the impetus for forming Black 47 and writing about Stephen Foster/Five Points came from Charles Dickens’s account of his visit to the Five Points. He wrote about the music and dancing and the bands he’d heard composed of African-American and Irish. I was intrigued to know what they would have been playing. From that came the idea of Black 47 – what if you mixed Irish traditional music with the African-American music of 1989 – hip-hop? I was a big drum programmer back then and found that reels placed across hip-hop beats worked wonderfully – that the music was different from anything I’d ever heard: Listen to “Paddy’s Got a Brand New Reel” and “Home of the Brave” from the Black 47 “Independent” CD.

I began to wonder about Foster at that point, too; in what way was he influenced by the music he was hearing in the Five Points dance halls. So, all these years later I’m working on a new production of “Hard Times” and promoting a Black 47 CD – all because I was into Charles Dickens back in 1986. Crazy world!

Q. Also on the new CD is “The Ballad of Brendan Behan” – it’s almost hard to imagine that this is the first time Black 47’s done a song about him. What has Behan, as a writer and as an historical figure, meant to you?

LK. Apart from our early version of “Patriot Game” – again putting an odd hip-hop beat beneath the greatest protest song – I never wrote anything about Brendan, probably because Shane McGowan was so influenced by him and if you’re an Irish songwriter you should keep as far away from Shane as possible – he’s such a powerful writer. Like most people I was probably more influenced by Brendan’s public persona than his writing. He was the first Irish celebrity and he was ours; not some academic or Anglo-Irish toff but a working class guy who left school at 13. I did admire “The Quare Fellow” and “The Hostage,” when I became a playwright in the early 1980s.

Q. Pretty much right from the beginning, Black 47’s music has sought to explore the ties between Irish and other cultures, especially black and Latino. Can you talk about that connection?

LK. I moved straight to the East Village when I came to New York City and lived among the black and Latino people. It was a whole new life and I could be whomever I wanted. Then I began playing up in the Bronx around Bainbridge Avenue and 204th Street – it was an Irish area completely surrounded by Puerto Ricans and Dominicans. The Irish up there had no connection with their neighbors. But the cultures seemed very similar to me: Catholic, family-oriented, with a fondness for drinking and music. I suppose being a musician I wanted to know how they made their music. But I also enjoyed their culture and they opened me up to new ways of looking at things.

So, it was very natural for me to incorporate those outside elements in my own music and writing. To me that intersection with those Latino and black cultures was an opportunity not to be missed and I’m still harvesting the possibilities – take a listen to “Salsa O’Keefe” or “Let The People In” on “Last Call.”

Q. Being part of Black 47 has never impeded you from getting involved in other projects and activities. What are some current or upcoming things on your plate?

LK. Well, I’m spending a lot of time developing “Hard Times” – which had two successful NY productions – into a bigger project. It’s been optioned by some big-time producers and they’ve encouraged me to take the Stephen Foster story and the Draft Riots of 1863 and bring them into the world of the American Civil War in 1863.

Q. The arrest of Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams last month prompted a great deal of speculation and commentary about the political situation in Northern Ireland – as well as its unhappy history – and how the peace process might be affected. Black 47 has certainly chronicled The Troubles over the years – is this a song with no ending?

LK. I hope not, but the real problem is that people expect The Troubles to be wound up neatly and packed away in a box. As ever, Yeats was on the money: “Much hatred, little room…” All the tragedies won’t fade away; they’re still there in the hearts and minds of people. It will take acres of time for the problems of centuries to resolve. The Adams arrest is only the tip of the iceberg. There are personal, tribal, and cultural animosities at play here, and the ubiquitous tit for tat of Northern Irish politics.

It amazes me that so many hurts have been put aside for the greater good. The Adams situation is a bump on the road, but it’s not a crater. In the end, people have children and want to see them get ahead in a reasonably just society. But the residue will remain. Look at politics in the southern states of the USA, still somewhat influenced by the Civil War and Reconstruction.

For information on Black 47, and to order their CDs, go to black47.com.