February 29, 2024

In early March 1776, Gen. George Washington rode out to Dorchester and reined in at the farm of Captain John Homans, who lived in “the upper end of town.” Homans’s acreage was full of white birch, and Washington ordered his troops to cut down the trees so that “the citizens of this and the neighboring towns…could cart them…on the night of the 4th, to [Dorchester] Heights.”

The Heights were dotted by “nine dwelling houses on the Neck, now South Boston.” The American Revolution was about to arrive at the front doors of those nine Dorchester households.

On the night of March 4, as American cannons opened up on British positions to divert the Redcoats’ attention from the Heights, some 300 wagons and carts teams piled high with timber for protective fences (fascines) creaked toward the slopes. So, too, did approximately 2,000 of Washington’s troops, lugging cannons dragged all the way from Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, the entire procession snaking forward with as much silence as possible. Washington, anticipating that the British would mount a bombardment and assault, had ordered his men to pack 2,000 bandages for the wounded.

Many residents of Dorchester hauled timber up the Heights on that icy, blustery night. The troops went right to work on the hills’ summits, erecting gun emplacements and bastions and positioning mortars and large-bore cannons with a direct view of British-occupied Boston and the harbor below.

The British commander, General Sir William Howe, awoke on March 5 to find the rebels on the high ground of the Heights and reportedly wrote, “The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month…on Dorchester peninsula…a work which the king’s troops had most fearfully dreaded.”

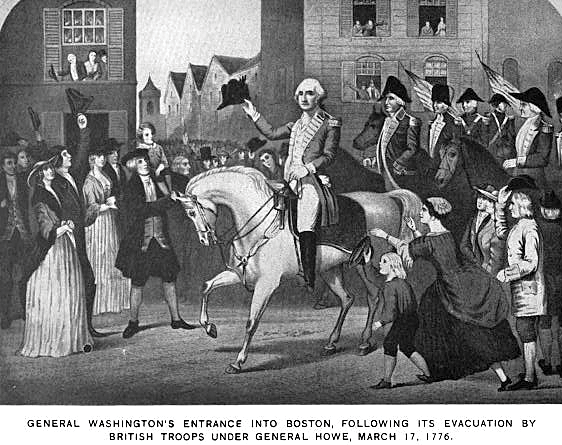

Facing catastrophe, Howe had no choice but to abandon Boston. His nearly 10,000 Redcoats boarded the 125 transports and warships in Boston Harbor and sailed away on March 17, 1776.

Washington knew that day was a holy day for the Irish, with many Irishmen having fought at Bunker Hill and having hauled those ponderous cannons up Dorchester Heights. He acknowledged both facts by ordering that the password of the day be “Saint Patrick.” Those Irishmen had witnessed what their countrymen on the “old sod” could only dream of: the British in full flight.

Today, 248 years later in Boston, March 17 fittingly marks both St. Patrick’s Day and Evacuation Day – the celebration alike of Ireland’s venerated saint and the day the Redcoats departed Boston for good.