June 22, 2021

The following is taken from the recently published “Untold Tales of the Boston Irish,” by Peter F. Stevens, a longtime contributor to Boston Irish.

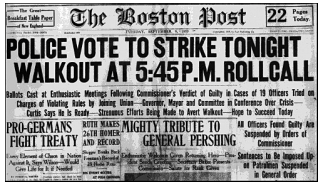

At 5:45 p.m. on September 9, 1919, as the Tuesday evening shift of the Boston Police began, 1,117 of the city’s 1,544 officers walked off the job. Nearly three-fourths of the department had gone on strike, most of them with Irish roots. To the horror of many Bostonians, the streets belonged to criminals for the moment.

That the Irishmen on the force had a long list of justifiable grievances and had sought to negotiate them meant little to Police Commissioner Edwin Upton Curtis. When the men in blue appealed for a modest increase in pay, they might as well have tried to squeeze blood from the proverbial rock.

Of equal concern to the financially strapped officers were their overly long shifts, which included grueling special details and a night in the station house every week, and the condition of those quarters. Rotting floorboards, cots infested with cockroaches and lice, crumbling plaster—these torments awaited the officers each day and night.

Founded by officers in 1906, the Boston Social Club had been the force’s grievance outlet. As word spread that the police intended to form a union, Massachusetts governor Calvin Coolidge reaffirmed his publicly stated opposition to, and unwillingness to deal with, any such “Local.” Four days before the police officially organized, on August 9, 1919, for a union under an AFL (American Federation of Labor) charter, Curtis had amended Rule 35 of the department’s Rules and Regulations to ban any police organization from aligning itself with any outside group except veterans’ organizations. Bostonians waited to see if the police would back down and obey Curtis’s edict.

The officers stuck together. Curtis responded on August 26 and 29 by putting 19 officers on trial for disobeying his amendment. On September 8, 1919, the 19 men were convicted of union activities, and their suspensions were extended. Within a few hours of the verdict, the Boston Police voted 1,134 to 4 in favor of a strike. They walked off the job late the following afternoon.

By 8:00 p.m., unruly crowds had gathered in downtown Boston. Suddenly, several miscreants broke into a tobacco store and ransacked it. As if on cue, mobs tore up and down Hanover and Washington Streets, looting, brawling, and terrorizing people. The upheaval soon spread to South Boston.

The undermanned police—72 percent of the 1,544-man force refused to report for work—could not contain the violence, and by daybreak, shattered windows, looted stores, and scores of battered citizens led Governor Coolidge to call out the Massachusetts State Guard. Commissioner Curtis mobilized his “volunteer police force,” condemned as scabs by the striking officers whose pleas for redress had been ignored and now condemned by the city and state governments.

On Wednesday, the mobs returned, battling with the volunteers, but as the guard was deployed in force that evening, some semblance of order returned. Although violence continued for several more days, with gunfire breaking out in downtown Boston, by the weekend, the troops had taken back the streets.

To the collective fury of Bostonians, and especially Yankees, who loathed the Irish, eight people had been killed—five by guardsmen—and many others wounded; property damage was extensive.

Despite the anger of many toward the striking policemen, city and state officials feared that Boston’s other unions would walk off their jobs in support of the officers, crippling transportation and other services. That scenario never developed. The police stood alone.

Some of the strikers began to waver, and feelers about a compromise went out to Curtis and Coolidge. AFL president Samuel Gompers sent Coolidge a telegram requesting that the police be re-instated and their concerns addressed later. “Silent Cal” responded with words that, in large part, would carry him to the White House: “There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, anytime.”

With the Massachusetts State Guard still patrolling the streets, Curtis filled out the ranks of his new police force, adding many more “real Americans.” The term “Good American Yankees do not strike” was the sentiment of letters imploring Curtis to shave Irishmen from the force. He was only too happy to swing with the anti-Irish tide.

None of the officers who walked from their stations on September 9, 1919, got their jobs back. Most were Irish. The bitterness of the fired policemen and their families endures among their descendants to the present day. While the issue of public safety was—and still is—debated, many in the community long viewed the Boston Police Strike as Yankees versus Irish.

On two facts, historians largely seem to agree: the heavily Irish police force did have legitimate grievances; however, the walkout did result in a crime spree on Boston’s streets, posing a genuine threat to public safety.

Still, one can only speculate what might have happened if Curtis and company had responded earlier and more sympathetically to the men in blue’s legitimate concerns. The strike remains a controversial chapter in the history of Boston, labor, and America.