July 2, 2020

In June and July of 1837, trouble simmered in Boston, and the unrest exploded on the sultry afternoon of June 11 near and along Broad Street downtown. Fire Engine Company 20 had just returned to its station on East Street, having quelled a blaze in Roxbury. A few firemen had trudged wearily to their homes, but most went to a nearby saloon for a few drinks.

When they headed back toward the firehouse, they walked straight into a crowd of 100 or so Irishmen on their way to join a funeral procession around the corner on Sea Street. A collision was inevitable, according to the historian Edward Harrington: “The Boston firemen, the protagonists in this drama, were then almost entirely drawn from the native [Yankee] stock, and chiefly from those poorer streets of the population among whom hostility to the Catholics and the Irish was fiercest.” Several of the firemen moving toward the mourners reputedly had a hand in the burning of the Ursuline convent in Charlestown three years before.

Accounts from publications circulating at the time and from historical records of the archdiocese of Boston tell the following story:

The groups passed each other on that summer’s afternoon with little more than surly stares, and the engine company had nearly made it through the crowd, which “seemed peaceable enough,” without incident. One engineman, however, 19-year-old George Fay, “had lingered longer than his comrades over his cups.” A cigar dangling from his lips, he either shoved several of the Irishmen or insulted them.

Within seconds Fay and several of the Irish were flailing away. Fay’s comrades rushed to help him, but, “being badly outnumbered, got the worst of it, and two of them were severely beaten” by the Irish. The enginemen fled to their station at the order of Third Foreman W.W. Miller.

If Miller had merely barred the station’s doors, many witnesses later agreed, the pursuing Irish would soon have turned back to the funeral. Miller, though, “lost his head completely…carried away either with fear or with rage and thirst for revenge.” He issued an emergency alarm so that every fire company in Boston would come to East Street “to take vengeance on the Irish.”

The Irish had begun to disperse, but that did not stop the men of Engine Company 20 from rolling their wagon into the street and sounding its bell in a false fire alarm. Then Miller dispatched men to ring the bells of the New South Church and a church on Purchase Street. One of the firefighters dashed to Engine Company Number 8, on Common Street, with a wild message: “The Irish have risen upon us and are going to kill us!”

The Irishmen who had fought with Company 20 were now following the funeral procession of a hearse and several carriages trailed by about five hundred mourners. The cortege wound its way north onto Sea Street en route to the Bunker Hill Cemetery in Charlesttrownj.

Company 20, with Miller leading, pursued the Irish. “Let the Paddies go ahead,” a fireman shouted, “and then we’ll start!” An onlooker saw the enginemen rush toward Sea Street and the procession with huzzas and cries of “Now look out! Now for it!”

The Irish mourners had walked only a block before another band of firemen, Company Number 14, approached. At the sight of the Irish, an engineman cried, “Down with them!”

Nearly at the same moment, the procession turned onto New Broad Street (near today’s South Station)—and directly into oncoming Engine Company Number 9. The horse-drawn fire wagon veered into the mourners’ ranks, scattering and knocking down men, women, and children. The Irish “jumped at the conclusion that Number 9’s men had intentionally insulted and assaulted them.”

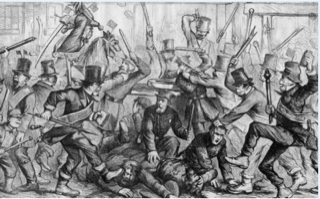

A melee erupted, with Miller, Fay and the rest of Company 20 arriving to join the fray. Fists and kicks flew in all directions, screams of rage and pain pealing along Broad Street. Sticks, cudgels, and knives soon materialized, and stones, bricks “and any other missiles that came to hand” slammed against heads and hearse alike.

The Irish and the enginemen would give starkly contrasting accounts of who started the brawl. The Yankee version was that Number 9’s engine did not hurt anyone and that the collision was “accidental.” To the Irish, the firemen’s version “did not escape charges of whitewashing.”

Those who had been following the hearse, as well as other witnesses, contended that George Fay, “the very head and leader of the quarrel…seized the rope and guided the engine in among the marchers, while some of the firemen tried to kick Irishmen, and some cried ‘Down with them! Trip up the horse!’”

One fact iscertain: The brawl soon swelled into a full-scale riot. The hearse’s drivers inched their way up Broad Street and eventually reached Charlestown, but the procession was “quite broken up.”

Irishwomen and others from the shattered funeral march ran to Broad Street with shrieks for help and fear-embellished claims that the firemen were killing the Irish and that the Yankees had toppled the hearse, smashed open the coffin, pitched the corpse into the street, and desecrated it. From all corners of the neighborhoods stretching along the waterfront, Irishmen rushed to the fight. Additional engine companies also poured onto Broad Street, where groaning and unconscious men lay crumpled atop the paving stones.

Crowds of spectators, Irish and Yankee alike, further clotted the street, cheering and exhorting their opposing sides until the brawlers “were excited almost to a point of frenzy.”

The weight of numbers lay with the firemen, their ranks buttressed by Protestant workmen, and they drove the Irish all the way down to the entrance of Old Broad Street, a gateway to the Irish neighborhoods. Realizing they were now fighting for their very homes, immigrant men, women ,and children tore bricks and stones from their own hearths to hurl at their foes.

As the engine companies and their workmen allies scattered Irishmen and surged into the narrow streets, they chased or dragged Irish families from their homes and plunged into an orgy of looting. Edward Harrington writes:

“Wherever the marauders broke in, they smashed windows and doors, stole whatever they coveted, and then proceeded with savage thoroughness to destroy everything else. Clothing was torn to shreds, shoes were cut to pieces; furniture and household goods of all kinds were thrown into the streets. Featherbeds were ripped up and their contents scattered to the winds in such quantities that for awhile, Broad Street seemed to be having a snowstorm…the pavement in spots…buried ankle-deep in feathers.

For immigrants who had been rousted from their cottages in Ireland and had seen their homes tumbled by landlords and British troops, the scene was sickeningly familiar. The looters trashed scores of households.

There is evidence that a few firemen, despite their brawling with the Irish that day, actually plundered homes. The blame for the break-ins falls largely upon “stout [Yankee] loafers and young hooligans” who trailed the engine companies, urged them on without joining the fight, and “seized the chance” to plunder.

Although continuing the fight, the Irish fell farther back from the overwhelming Yankee gangs. By 6 p.m., crowds of terrified immigrants crowded the wharves, their backs literally to the water’s edge.

Help came belatedly from a source on which few of the Irish would have counted. Mayor Samuel A. Eliot sent ten companies of infantry and the Boston Lancers, cavalry, on a sweep along Broad Street and the adjacent Irish neighborhoods. The fire companies and their cohorts scattered. After nearly three hours of fury, the Broad Street Riot came to an end.

Although heads had been cracked and blades and clubs had torn men open, miraculously, no one had been killed. The number of wounded was so large that it could not be tallied accurately.

In July 1837, 14 Irishmen and 4 Protestant men arrested during the brawl stood trial in front of a jury entirely composed of Yankees. Three of the Irish were sentenced to several months in jail. The Protestants were found “innocent.”

Not even the fury of the Broad Street Riot could make Boston’s Irish abandon their foothold along the waterfront. They had dug in and would refuse to be dislodged during decades of discrimination to come. On that June 1837 day, they had battled as a community.

The chief sources for the details in this article are “History of the Archdiocese of Boston,” Vol. 2, pp. 243-251; and the 1837 publications the Boston Daily Atlas and the Boston Post.