June 5, 2020

DUBLIN – A march in the Irish capital on June 1 in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and the oppressed in America included a journey past Dublin monuments and landmarks that evoked history and the connection between Ireland and America. As I joined the masked and determined crowd on O’Connell Street, one t-shirt slogan caught my eye: More Blacks, More Dogs, More Irish, a satiric reference to signs posted in UK shop windows after World War II: No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish.

The announced gathering point was the Spire, a soaring needle in the center of Dublin. It was once the location of Nelson’s Column, built in 1805 celebrating the admiral’s victory at Trafalgar. He glared down on Dublin’s onetime British subjects for generations. Nelson himself had died in the battle.

In 1966, as the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising approached, an Irish republican placed a bomb at the top of Nelson’s column just as visiting hours were ending, but because of ‘the damp,’ the bomb fizzled. The man went back the next day with another bomb and this time it worked, blowing half the column off, leaving an ugly stump. The column and the British domination that it represented were not missed, so the Irish government removed the stump. President Eamon DeValera suggested a headline to the Irish press: “British Admiral Leaves Dublin by Air.” They found Nelson’s head, which luckily had not fallen on anyone. and, after many adventures, it ended up in the library on Pearse Street and is rarely seen. Debate on what to put in Nelson’s place on the boulevard went on for decades, and finally, in 2003, the soaring spire was installed.

The initial cluster of BLM protesters centered between the Spire and the statue of Jim Larkin, the ‘voice of labor’ who led the 1913 Dublin tramway strike against “Murder Murphy,” the publishing magnate who also owned the tram system and mercilessly crushed Larkin’s strike. Born in a Liverpool slum to Irish parents, Larkin later was a labor organizer of the Wobblies in America, starting in 1914. He was imprisoned in the first “Red Scare,” then pardoned and deported back to Ireland by Al Smith in 1923. Larkin’s most famous quote was: “The great appear great because we are on our knees: Let us rise.”

The strike was defeated but the seeds of his Dublin action sprouted three years later. Across the street from the Larkin statue is the General Post Office, where in 1916 the Irish Republic was proclaimed for the first time, the republican flag raised, equal rights for Irishmen and Irishwomen declared, blood shed, and the rosary prayed at night with the assistance of a Capuchin Friar who would sneak in over the battle lines after the shooting had stopped to anoint the dying. Six Days later, with the city center in ruins, Padraig Pearse surrendered at the GPO, ceremonially handing over his sword to British General John Maxwell. By executing the signatories to the proclamation, Maxwell strewed the seeds of further rebellion across the island that culminated in the war of independence, a partitioned Ireland, and a civil war.

As the protest between the Spire and the statue of Jim Larkin set off, there were a surprising number of African Irish, a smattering of French-speaking West Africans among them, leading the sizable crowd – reports indicated 5,000. Chants resounded: “Black lives matter” … “I can’t breathe” … and call-and-response chants like: “Say his name!” “George Floyd!” … “What do we want? Justice!” … When do we want it? Now!” One sign read “We don’t assassinate presidents like we used to.”

There were baseball hats from Boston, New York, Chicago, L.A., and San Francisco. The baseball diaspora. I saw my friend Gerry in the crowd. COVID-19 masks were everywhere, many with the slogan “I can’t breathe” scrawled across the front of the mask. The Gardai were helpful and courteous to the protesters, sometimes sharing a laugh. The Irish Guards were not the police being protested yesterday. They are in Minneapolis, L.A., Chicago, and New York where cousins and siblings live and send baseball caps to their loved ones “back home.” This gathering was about solidarity.

The crowd began to move south down O'Connell Street, passing the enormous statue of Daniel O’Connell, “the great Liberator” who used politics, rhetoric, and legal expertise to fight for Catholic emancipation for his people all his life, culminating in 1829 when many but not all restrictions on Catholics were lifted. O’Connell later formed a deep and unlikely friendship with Frederick Douglass after Douglass’s New Bedford- based Quaker friends who had paid for his manumission correctly judged that getting Douglass out of the USA and over to Ireland in 1845 was the only way to ensure he would avoid recapture by the slave catchers. In fact “Slave patrols” and “Indian patrols” are the origin story of policing in America. From New England to the Carolinas to the west and throughout the country, the history of policing is enmeshed in slavery and the dispossession of the native peoples. After living in Ireland among the Irish and learning their history of oppression and experiencing Irish culture, Douglass referred to the Irish people as the “White Negro.”

O'Connell's devotion to his Catholic faith was so fervent that in 1847, late in his life with his health deteriorating, he attempted a pilgrimage to Rome. He died in Genoa, but he had left specific instructions that his heart be removed from his body and delivered by hand to Rome. His work to advance freedom, justice, and equality was also passed along.

We marched across the River Liffey on O’Connell bridge where in 1963 John F. Kennedy’s motorcade was greeted by throngs of admirers. Despite his chronic back pain, Kennedy, overwhelmed by the crowds of Irish all over Dublin, stood in the open car for the entire tour steadied by a cross bar, as DeValera sat beside him. People say it was as if the entire island came to cheer the president with a hero's welcome. Five months later, he was murdered.

But this day was about the death of George Floyd. His methodical and cold- blooded murder by a uniformed police officer has been called a lynching, but to me it seemed worse than that. It is true that the KKK were often policemen and judges, but even they knew that extra judicial executions were illegal as well as wrong, so they should probably wear a face covering hood. This officer was not hiding his identity, was not hurried, under duress, or panicked, as most white officers claim when they kill a black man in America.

A painting of George Floyd’s likeness was hoisted above the crowd of marchers and we marched on. The call and response of the forward flowing protest continued: Say his name! GEORGE FLOYD!! Say his name! GEORGE FLOYD! SAY HIS ----- NAME ! GEORGE FLOYD! Hearing his name over and over again affected the emotions of the marchers. Tears were shed for a man none of us knew. His murder has laid bare the endemic and systemic racism in the United States and the broken, sclerotic politics that has been unable to deliver real reform or results. The government has lost the consent of the governed. Even Barack Obama could not deliver the change he had promised once US Sen. Mitch McConnell devoted himself to pure obstruction.

We went down D’Olier street, turned right at College Green in sight of what used to be an enormous equestrian statue of William of Orange on Dame Street. The statue of the man most despised by Catholics and nationalists was finally removed in 1938 after it had been bombed and severely damaged several times. The scars of a disputed history.

We proceeded past Trinity College along Nassau Street up Kildare, and took a left at St. Stephens Green, another site of bloody sacrifice in 1916 where rebels dug entrenched positions in the park, but took heavy losses from British gatling guns. Weapons from World War 1 battlefields, they were mounted on the roofs of their Officers Club and the Shelbourne Hotel, raining hell on the rebels. We headed down Merrion Row, and Baggot Street lower. It was about this time that I realized I should have worn better shoes, but it was a sunny, fine day and I confirmed with another marcher where we were headed. Down Pembroke, we were greeted by observers on both sides of the road as if we were a parade on the way to the US embassy.

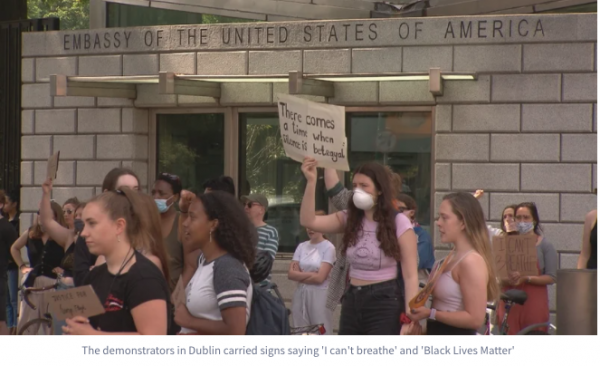

We arrived at the embassy, which was built between 1962 and 1964 in Ballsbridge, a leafy, beautiful, and expensive neighborhood. The chants continued. The bullhorn was not very effective for the speakers who were held up on shoulders. It did not matter. A musician went to his car to get an amp and microphone. That worked better. “Solidarity with our American brothers and sisters!” “Justice for black and brown people everywhere!” “Say his Name!” “George Floyd.”… “What do we want?” Justice!”… “When do we want it? Now!” The chants of thousands reverberated down the quiet leafy streets. En masse, protestors took a knee in honor of George Floyd.

In August 1927, cities around America and around the world protested the sham trial and executions of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. The apology proclamation from Gov. Michael Dukakis in 1977 did not exonerate them, but we all know they were innocent. “Two good men a long time gone, Sacco and Vanzetti are gone,” sings Christy Moore to this day.

When we were growing up in Boston in the ‘70s and ‘80s, we knew who Bobby Sands was. In 1981, my brother carefully cut newspaper clippings of all the hunger strikers and hung the pictures and stories on the wall. Ireland is returning the favor to us now, standing in solidarity with their cousins, brothers, and sisters who resist injustice in Boston, New York, Chicago and beyond with the words of one of the simple chants at the embassy:

“This is not okay! This is not okay! This is not okay!”

Was the Trump-appointed ambassador behind the walls listening? The president is not listening and does not care. It is up to the descendants of the people Frederick Douglass called the “White Negro” to stand with their black and brown countrymen and women and keep trying to make things better. We must, in the words of Samuel Beckett: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again, Fail again. Fail better.”

George Floyd was not a revolutionary, an anarchist, a campaigner, a reformer, a union organizer, a politician, or a hunger striker. He was not trying to change the world; he was just trying to live his life. But his murder has sparked the fight for justice.

Tim Kirk, a software professional, left Needham, Massachusetts, last December and settled permanently in Dublin.

Pictured: Screenshot from RTI.ie, as people demonstrated outside the US embassy in Dublin, demanding justice for George Floyd. A peaceful protest was also held outside the official residence of the US ambassador, Deerfield, in the Phoenix Park.