January 29, 2024

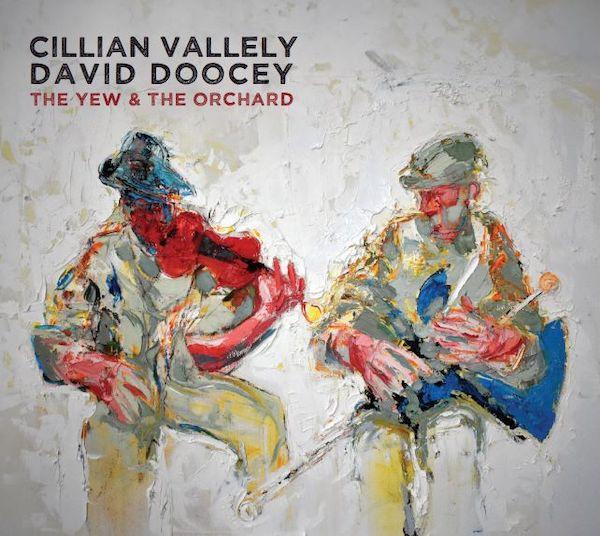

Cillian Vallely and David Doocey, “The Yew & the Orchard” • Vallely and Worcester native Doocey share some significant attributes, notably the strong presence of traditional music in the family: In fact, both have siblings who, like themselves, are supremely accomplished musicians. Vallely (uilleann pipes, whistle, low whistle) is well known as a founding member of trad supergroup Lúnasa and has appeared with everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Natalie Merchant; Doocey (fiddle, concertina, bouzouki, guitar) owns multiple All-Ireland titles and in addition to membership in bands like Gráda and Blás has made music with Sharon Shannon, Martin Hayes, Finbar Furey, and other luminaries. “The Yew & the Orchard” – the title is a reference to natural features of their respective locales, respectively Mayo and Armagh – is their first album together, and there is every reason to hope there will be more. The pair display simply top-level musicality as well as an inspired choice of material, including some of their own work.

Adding to the pleasures of “The Yew & the Orchard” are contributions from a couple of those aforementioned talented siblings (there are more than one apiece in both families) – the pianist Caoimhin Vallely and the guitarist Patrick Doocey – plus Sean Óg Graham (a member of Beoga and currently on tour with Karan Casey) on guitar.

You can’t do much better than the set of traditional slip jigs, “James Byrne’s/Humours of Whiskey/Up and Down Again,” which in addition to the superlative performance (Patrick Doocey included) is an excellent example of how to assemble a medley for a contrast of ambiance and tone. There’s also an outstandingly constructed trio of reels, beginning with Doocey’s own “Worcester Reel” (yes, named for that fair city) – which features an especially striking Dooceys’ duet – and amped up by Vallely’s entry on “St. Ruth’s Bush,” finishing with another Doocey original, “Gay Cassidy’s.” Vallely’s “Cider Shack” ushers in a set of slides that segues into “Bolt the Door” via the O’Neill Collection and – from the repertoire of Kerry’s own Padraig O’Keefe – “I’d Rather Be Married Than Left,” which deserves at least as much affection for its joyous melody as its quirky title.

“The Yew & the Orchard” has plenty of kick, to be sure, but more serene moments, too: Witness Doocey’s playing of a Junior Crehan reel, “West Clare Railway,” Graham’s guitar picking neatly complementing the bowing on the A part, followed by a moody Dorian-mode “Jug of Punch.” Vallely leads in on an air from Munster, “A Ógánaigh An Chúil Chraobhaigh (O Young Man of the Flowing Hair)” – one of those tunes tailor-made for the pipes – and then Doocey introduces the D-minor “Peacock’s Feather” hornpipe, with Caoimhin Vallely’s splendidly empathic backing.

Vallely and Doocey show no qualms about going outside the Irish domain. One track has an Americana tint, as Vallely plays slow, mournful low whistle to open the old-timey tune “Elk River,” and then Doocey brings up the tempo, multi-tracking his own bouzouki and guitar backing as well; they segue into “Ryan’s,” written by Jack Herrick and Clay Buckner of famed North Carolina string band Red Clay Ramblers.

Elsewhere, an ebullient set of hop jigs – jauntily escorted by Patrick Doocey – opens with “Tha’m Buntåta Mór (The Potatoes Are Big),” a piece of Scottish Gaelic puirt-a-beul from Highland piper Allan MacDonald, leading into a pair of Vallely originals. Another Highland piper, James MacKenzie, was the source for the brisk 9/8 march “Heights of Dargai,” followed by “Paddy Joe’s,” which Doocey learned from Mayo accordionist Paddy Joe Tighe. And the album’s final track – which starts with “Big Pat,” associated with renowned uilleann piper Leo Rowsome, and a Donegal variant of “Scotch Mary”– ends with a Shetland reel, “Oot Be Est Da Vong,” which translates to “east of the vong,” referring to a cherished fishing area.

An earlier draft of this review ended with the observation that, given their respective schedules, it might be difficult to see Vallely and Doocey on the same stage – making this album all the more a cherished listening experience. But here’s a late-breaking bulletin: Vallely and Doocey, along with guitarist Alan Murray, will be at Boston College’s Gaelic Roots series on April 25 at 6:30 p.m. (see bc.edu/irish) Catch ’em live, while you can.

[cillianvallely.com; daviddoocey.com]

An opportunity to contemplate the Quebecois-Celtic connection.

Genticorum, “Au Coeur de L’Aube” • We’ve long since passed the time when it seemed de rigueur to provide an explanation for including Quebecois music in the context of things Celtic. Performers such as Celtic Fiddle Festival, Becky Tracy & Keith Murphy, Sharon Shannon, and Grosse Isle, among many others, have habitually incorporated Quebecois tunes or songs alongside those of Ireland and Scotland in their repertoires. Festivals and concerts that showcase Irish, Scottish and Cape Breton artists have frequently included Quebecois musicians in the line-up – such as this year’s BCMFest, which featured Le Vent du Nord in the Nightcap finale concert. People get it.

That doesn’t mean, of course, there isn’t merit to contemplating the Quebecois-Celtic connection. So, the latest release by the trio Genticorum, whose members include one-time Boston-area resident Yann Falquet, presents an opportunity to consider this topic, even while appreciating “Au Coeur De L'Aube” – and Quebecois music in general – on its own terms.

But first and, really, most importantly: This is simply a wonderful album. Energetic and dynamic as Genticorum is, there’s always been a special conviviality, even gentleness, in their music. Some of it has to do with Nicholas Williams’s flute, which adds a soulfulness to their sound, and his accordion playing has a similar quality; it all sits very well alongside the brilliance of Pascal Gemme’s fiddle, mandolin and foot percussion, along with Falquet’s guitar and guimbarde (jaw harp). Their voices, whether solo or together, are robust yet infused with an affability and warmth.

“Au Coeur De L'Aube” is brimming with familiar, irresistible Quebecois/Genticorum traits: the chansons à réponse, or call-and-response songs, like “La Bateliere” or “Belle Alouette au Champs,” which may make you regret not having taken French in high school; the exhilarating, infectious rhythms, especially those produced by Gemme via both fiddle and feet (the “Le Persuadeur” set, which also includes nifty jaw’s harp by Falquet); the attentiveness to arrangements, such as the slow, steady acceleration on the set “Cardeuse et Lachance” and, in another medley, Williams’s accordion layering Falquet’s stately “La Petite Marche” – which begins the track – on an Irish tune, “Byrn’s March,” played here as a reel; and the trio’s gorgeous harmony singing on “Goutons du Plaisier,” a meditation on the parallels of love and strong drink.

As Falquet, Gemme, and Williams note, the Quebecois/Celtic relationship is a complicated but hardly unique one: a case of native music retaining some of its distinctive characteristics even while taking on elements introduced by immigrants and other visitors.

“Like all traditional music, Quebecois is a mix of several influences, and you can separate it into multiple different repertoires,” says Gemme. “There’s a part of the repertoire that comes from the heydays of the quadrille, a type of dance, and that repertoire has very few links to Celtic music. If we take a listen to the jigs and reels repertoire, however, that part of our tradition is very heavily influenced by Scottish reels and Irish jigs. Some tunes we play in Quebec are basically Irish tunes that were given a French name. Others are local compositions that were passed from generation to generation in the Celtic style and others are somewhere in between Celtic and other influences: medieval, classical, American, English.

“It is widely known in the population that we owe a lot of that music’s sound to the Irish immigrants, but a little less so for the Scottish influence – even though it is as important as the Irish. That is clear to most Quebecois musicians when they start learning tunes. It was for me because my grandfather played American, Irish, Scottish, and Quebecois tunes. He lived in a rural community where all those influences were still present in the form of actual people playing the music around him and they shared tunes from time to time.”

Where Genticorum is concerned, their repertoire encompasses almost exclusively Quebecois tunes, or others of their own compositions. Falquet can name but 3 exceptions through their 11 recordings: one tune from Brittany, one from Finland, and “Byrn’s March.” Still, he adds, while “we didn’t record many tunes from these traditions, I think we drew a lot of inspiration from how these bands arrange music.”

Though the flute and whistle have a strong presence in the Irish tradition, such wind instruments are more on the periphery of Quebecois music, according to Williams. Still, chances are that at a moderate-sized Quebec session, you’ll see a flute poking its head out amidst the sea of fiddles and accordions. And Williams can reel off a number of examples of notable flute players in the Quebecois scene, such as Genticorum’s original flutist Alexandre DeGrosbois, now playing with Mélisande Electrotrad; others include Jean Duval, Daniel Roy (on the La Bottine Souriante album “Chic and Swell”), Benoît Fortier (Les Chauffeurs à Pieds), Marie Marceau, Élise Guay, and Isabelle Doucet.

“As there is a fair bit of common ground between Irish and Quebecois traditional music, many flute players playing Irish music in Quebec will stray to varying degrees into Quebecois trad music community,” he says.

Having accompanied musicians from elsewhere in the Celtic spectrum, notably Hanneke Cassel and Katie McNally, Falquet has a particularly keen appreciation for the subtleties of “the swing of the melody player,” as he puts it. “I find that even within Irish or Scottish music or within Quebec music there can be a wide variety of styles, from very even notes to ones that are heavily swung. And then the same would apply to the choice of chords I’d play: droney and linear to jazzy and with a lot of motion. All these choices are more related to the tune itself and the style of the melody player than on the whether it’s from Quebec, Ireland, or Scotland.”

That said, adds Falquet, the Quebecois foot percussion does make a difference in his accompaniment: “In that case I’ll try to lock my playing more with the feet then with the fiddle. And for Hanneke Cassel, if I can sound like U2 and Keith Murphy at the same time, I know I’m on the right track.”