July 31, 2023

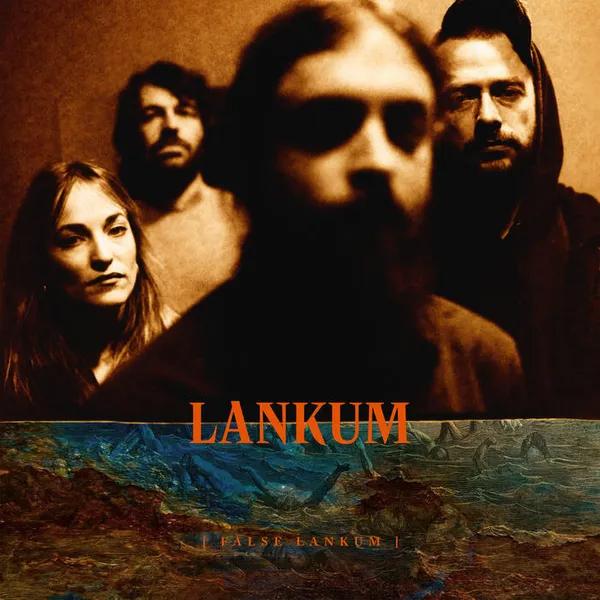

The fourth album from the Dublin quartet of self-described “folk miscreants” finds them continuing to meet expectations by defying them.

Starting out as Lynched, an experimental psychedelic folk-punk duo of brothers Ian and Daragh Lynch, the band took shape with the addition of Cormac Mac Diarmada and Radie Peat, changed its name after its debut album, and proceeded to carve out a unique place in the Irish music scene with a repertoire of centuries-old ballads from Irish and American traditions; Irish folk, street, Traveller, and music hall songs; covers of contemporary songs; traditional tunes; and their own variously trenchant, devastating and elliptical compositions, all joined to a musical persona that has grown increasingly, even bewilderingly multifaceted. (Aptly enough, iTunes categorizes “False Lankum” as “unknown genre.”)

So, on this one album, you have the tragic ballad “Lord Abore and Mary Flynn,” presented with gorgeously harmonized singing from Peat and Daragh Lynch and accompanied only by his fingerpicked acoustic guitar (plus some very bassy chording from Peat on accordion), and then you have tracks suffused with atonal, sonic experimentation – or totally comprised of it, in the case of the three tracks titled “Fugue.” Meanwhile, the band’s laid-back, reverb-heavy take on “Clear Away in the Morning,” a wistful maritime song written by revered Maine singer-songwriter Gordon Bok, contrasts with the hard-edged, driving, supernatural sea-faring ballad “New York Trader,” punctuated by an equally energetic reel of American origin, “Big Black Cat.”

Two tracks stand out, arguably, as the most representative of Lankum’s here-and-now. “Master Crowley’s” is a rather solemn but invigorating E-dorian reel, often associated with Donegal-born fiddler Hugh Gillespie. A staple of Lankum is their willingness to display the unruly, even cranky nature of some of their instruments, like Ian Lynch’s uilleann pipes or Peat’s accordion; on “Master Crowley’s,” it’s a trio of concertinas played by Peat, her sister Sadhbh, and Cormac Begley. About halfway through the track, the three begin to recede far into the background, supplanted by a throbbing bass, a rhythmic clang, and other disparate noises, until the concertinas return for the final minute or so.

There’s a similar approach on the album’s 13-minute finale, “The Turn,” a band original that is of a piece with their bleaker observations on the human condition (such as “The Wren” on their previous album). The song’s dirge-like verses are interspersed with an up-tempo but not especially uplifting refrain: “Turn, we’ll find better days/Burned to the ground/Mourn, it’s the only way/We’ll make a sound.” But at about the seven-minute mark, vocals and instruments drift away and an ominous sonic squall of mounting proportions moves in for the remainder of the track.

(Probably a generation-specific observation here but listening to “Crowley’s” and “The Turn” is reminiscent of turning a radio dial and landing on a frequency partly occupied by two different stations. Sometimes, if you adjust the antenna or turn the radio itself a certain way, one of the two will become dominant, but the other never completely fades away.)

So, what to make of all this?

The signs and portents for the evolution of Lankum have been there all along. While their earlier albums included music hall japes like “Daffodil Mulligan” or satirical songs from various origins (“Father Had a Knife,” “Salonika,” “Sergeant William Bailey”), their originals – “Cold Old Fire,” “The Granite Gaze,” “The Young People” and the aforementioned “The Wren” – in particular spoke to a concern and disenchantment over contemporary Ireland’s inability, or unwillingness, to address certain social and economic issues both past and present.

In a 2020 Boston Irish interview, Daragh Lynch explained the band’s connection to traditional and other folk music.: “If you look into the background of traditional songs and ballads, there are many that came about as forms of protest, airing grievances about injustice and inequality. You can learn a different kind of history through these kinds of songs: what it was like to be a woman, to be poor, to work the hard jobs. Those are often the songs that have captured our attention, and they’ve also served as models or inspiration for the songs that we’ve written.”

But, as Ian Lynch noted a year earlier in Boston Irish, Lankum doesn’t view the music they play – whether from traditional or contemporary sources – as “museum pieces that you’re handling with white gloves.” They’ve shown a particular propensity to slow things down, the better to explore the full emotional or experiential content within the lyrics, and integrate extensive instrumental passages – as a result, many of their album tracks are upwards of six, seven, eight minutes or more. As Daragh Lynch has explained, this approach “brings about a kind of meditative state [that] can make people more attuned to the song, and spend more time listening to the words.”

The use of modern, electronic, ambient-sound type of textures – such as on the “Fugue” tracks – has been an enduring interest of the Lynches, one supported by the band’s producer and longtime associate, John “Spud” Murphy, and it has become increasingly prominent in their work.

“We’re just ourselves, and the kind of music we like – like the music of the Travellers – tends to be on the rough, unpolished side, and to our minds, more emotionally intense,” summed up Ian Lynch in 2019. “No, we’re not trying to make some kind of point in the way we play; the sounds we make are what make sense to us.”

The question, then, is will it make sense to you, the individual reading this column? If you get the impression that this typist is wrestling with that question himself, well, you’re not far wrong. Is there a rhyme or reason for the apocalyptic soundscape at the end of “The Turn”? Perhaps an appropriate if unnerving coda, given the overall tone of the song as well as the severity expressed in the lyrics. What’s the deal with the three “Fugues”? Are they supposed to be a kind of reset button, keeping the listener from becoming too inured to the more familiar musical forms elsewhere on the album? And why not let the concertina trio in “Master Crowley’s” stand as is?

Maybe it’s actually OK to not be sure, and simply zero in on what are the most accessible or relatable aspects of “False Lankum” (the title, by the way, refers to one of many versions of the very dark traditional ballad from which the band takes its name). Peat’s singing has always been a big part of what makes Lankum such a compelling listen, her commanding voice fitting that rough-beauty dynamic of the band. And leading off the album is her rendition of “Go Dig My Grave,” learned from the singing of American folk music icon Jean Ritchie. There are versions upon versions of this song going back four centuries and also known as “Died for Love” and “The Brisk Young Farmer,” among many other names, but the premise is the same – a young girl in despair over a false (there’s that word again) lover – and the outcome is, sadly, all too relevant today as it was 400 years ago.

As the song ends, Peat’s voice (the other band members also sing on the chorus) gives over to a coalescing montage of acoustically and electrically generated sounds and rhythms, and it’s not at all fanciful to visualize some grim procession leading not just to the grave but to the very heart of misery itself.

That kind of deep, emotional connection is what folk/traditional music is all about, and “False Lankum” shows that Lankum’s interest in it is quite genuine.