October 6, 2022

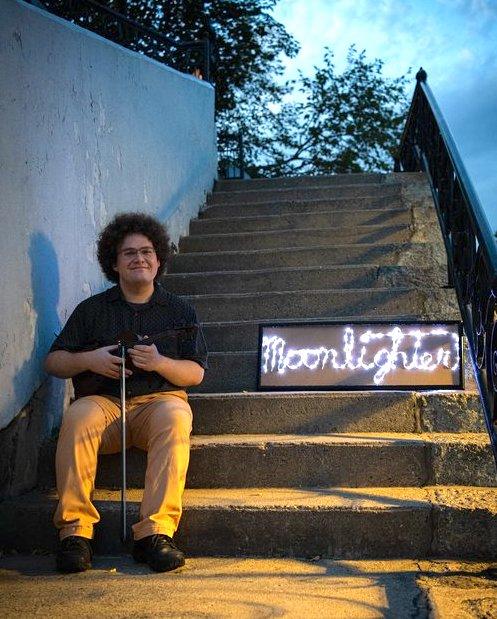

“For me, traditional folk music isn’t a hobby or a leisure-time activity; it’s a community.” Steve Manwaring photo

It’s a niggling question familiar to the evenings-and-weekends musician who holds down a so-called “real job” (as if managing a full-time musical career isn’t a real job, but never mind) while performing concerts or participating in jam sessions off-hours: Am I really good enough to play music with the people who do it for a living?

In the case of Boston-area fiddler Leland Martin, the answer is definitely “Yes.”

Not that Martin, a Natick resident who works as a chemistry prep room manager at a local college, didn’t ask himself that very question for years – especially when he encountered other part-time musicians who had full-time, non-musical occupations, and who, to his mind, seemed quite adept at striking a balance between the two.

But the experience of recording his recently released first album, the aptly named “Moonlighter,” removed any lingering doubt Martin might have had about putting himself and his music out there. He recorded the CD with some of the finer Celtic musicians in Boston and elsewhere in New England: Neil Pearlman (keyboards, accordion, tenor banjo), Conor Hearn (acoustic and electric guitar, bouzouki, tenor banjo), and McKinley James (cello); fellow fiddler Katie McNally served as producer.

“The whole process was rather surreal, but very rewarding,” he says. “I think a lot about the work Katie did, and I’m so grateful to her. She had some great suggestions and insights, and there was far less nudging of my style and ideas than I thought there might be. Working with Neil, Conor, and McKinley, all excellent, accomplished musicians, was such a pleasure.

He quips, “I said to myself, ‘Maybe I know something about this music after all.’”

As Martin explains, there’s an added significance to the album title: It refers to his working between multiple styles and interests as a fiddler – whether Irish, Scottish, Cape Breton, or elsewhere, or traditional, contemporary or original tunes – that he’s accumulated over the years.

While most of the tunes on “Moonlighter” are by Martin or other contemporary composers, the mix of styles and traditions makes it a quintessentially New England folk/trad album. The album often has the feel of a 21st-century contra dance, some tracks arranged in classic, straightforward fashion, others with a more modern, and ambitious, sensibility.

“Moonlighter” is thus an appropriate successor to Martin’s other, long-running project: playing through “Ryan’s Mammoth Collection” (“RMC” for short), a public-domain collection of more than 1,000 fiddle tunes from the New England folk scene in the 19th century. Martin has created a YouTube channel entirely devoted to RMC (originally published in Boston in 1887) and posted videos of himself playing the tunes for other musicians to listen to and be inspired to learn.

“RMC is a great window onto the music that was happening in Boston during the early 1900s,” he says. “It’s a mash-up of so many styles and influences, whether Irish, Scottish, Cape Breton, Appalachia, French Canadian, and so on. So it gives you a real sense of how rich the New England music tradition is.”

Martin was exposed early on to that tradition, as a youthful member of the Pioneer Valley Fiddlers, a multi-generational ensemble in Western Massachusetts that plays a repertoire of folk and traditional tunes and performs at fairs, St. Patrick’s Day celebrations, and other events.

“One thing the group was really great about was incorporating all types of fiddle music into their repertoire – Irish, Scottish, old-time. One minute you’re playing a march, the next you’re playing a rag.”

As a college student, he wound up sitting in with the duo of John Kirk and Trish Miller, a mainstay of the Northeast contra dance circuit; he later played with guitarist John Coté, part of the innovative contra dance duo Perpetual e-Motion.

“I think it actually took me a while to start thinking about what it means to play a tune in a ‘different’ style. It kind of blended together at first. The first Cape Breton fiddler I ever heard was probably Natalie MacMaster, but I just heard it as ‘fiddle music’ at the time. I was picking up tunes from her albums but I didn’t realize at the time that it was this really weird blend of contemporary and trad Irish and Scottish tunes. It was just a really cool sound to me.

“Then I started to meet more and more fiddlers in person, and when I was maybe 15 or 16, I first met Troy MacGillivray [another renowned Cape Breton musician] at a fiddle camp in Ontario. And the way he could just pull these tunes and lay them out for you – it kind of reminds me of those older epic poems, where everyone knows some parts of the story really well, but a good teller will make you see it in a new light. I just remember being really drawn into his playing, and from there it was really following threads to find all these other fantastic fiddlers.”

Settling into the Boston area brought Martin in contact with many such fiddlers – and other musicians – of quality, and he became a familiar figure at events and venues such as BCMFest, the Canadian American Club, The Burren, and The Druid. Even as he admired their abilities, he clearly made an impression on them, as he discovered when he recruited McNally to oversee “Moonlighter.”

“I’ll never forget the look of excitement on her face when I asked her if she’d produce the album; when someone you admire wants to take part in your project, that is such a confidence booster.”

Animated by the interplay between Martin, Hearn, Pearlman, and James, and the producer’s touch of McNally, “Moonlighter” is full of exuberance and grace, such as the medley of Irish tunes (“Rory O’More’s/The Coleraine/Cuil Aodha”) that evoke Martin’s contra dance days with Kirk and Miller, and “The Weird Strathspey Set,” which begins with the titular tune (composed by Martin, he explains, for a friend who felt “I played my strathspeys weird”) and is followed by three Scottish/Cape Breton-sounding reels he found in RMC, “Luckie Baldwin’s/The Wee Bit/Green Trees of Athol.” These tracks are a perfect representation of the Martin-Hearn-Pearlman-James ensemble’s finely coordinated vigor, Pearlman’s keyboards providing their characteristically energetic backing (occasionally doubling on the melody with Martin).

The “F Jigs” set begins with a winsome Martin-Hearn pairing on Martin’s “Non-Zero Chance,” and then James enters, filling out the sonic spectrum by matching Martin note for note; Pearlman lifts the transition to Ayelet Kirshenbaum’s major-minor “Jig for the Honeydew Tea,” and the quartet is at full strength for another Martin piece, “Recycling Thunder.”

If these tracks adhere more to the norm for Celtic/contra arrangements and ambience, others – especially those composed by Martin – push the boundaries. At one point during “The Kintsugi Waltz,” for instance, Martin drops out while Hearn unfurls a contemplative electric guitar improvisation set against Pearlman’s delicate chords, while James reintroduces the melody to set the stage for Martin’s return.

“Distant Schroers” is a tribute to the late Oliver Schroer, a genre-defying fiddler/violinist, composer, and producer whose portfolio included collaborations with Great Big Sea, Loreena McKennitt, and Irish flutist/vocalist Nuala Kennedy, three film scores, and an album he recorded while walking the Camino de Santiago pilgrim trail. Martin’s playing of the main theme, an accented 6/8 melody, functions as a recurring point of reference for the other instruments (including percussion), which coalesce behind him, take over for a freeform break in the middle (Hearn’s electric guitar holding sway), gradually re-form, and gather strength for the finish.

“That was definitely the most involved piece to put together, and one of the most satisfying,” Martin recalls. “I had a loose skeleton of a framework to start with, and we ran it every day for three days – and did it a little differently each time.”

Then there’s “The Hornpipe Sonata,” an improbable union of the two music forms referenced in the title – a sonata typically consisting of two to four movements or section, “each in a related key but with a unique musical character” (per Britannica.com). The piece originated as a college assignment for Martin and was, he says, “too fun not to include.” It bounces merrily along for a good seven minutes, Pearlman’s piano providing the connective tissue between the sections with various contributions from Hearn and James, and ends with an appropriately dramatic flourish.

“It was such a great time putting all these ideas together and coming up with ‘Moonlighter,’” says Martin. “I’ve had such encouragement and support from people like Katie, Neil, Conor, McKinley, and many others over the years, so for me, traditional folk music isn’t a hobby or a leisure-time activity; it’s a community.”

For more on Leland Martin and “Moonlighter,” go to tuneswithleland.com.