January 4, 2022

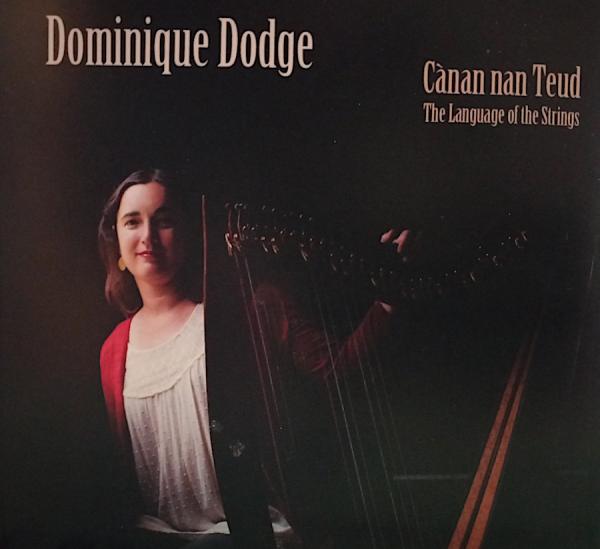

Dominique Dodge, “Cànan nan Teud (The Language of the Strings)” • If you’ve come to regard Celtic harp music as ethereal, reposeful, dainty, and wrapped in layers of mist and reverb – or even if you haven’t – this album is a very pleasant revelation.

Dodge, a New Hampshire native who has studied music at the University of Limerick and Scotland’s Royal Conservatoire of Music, puts the harp squarely in the Scots Gaelic tradition, specifically dance music and the fascinating domain of puirt-à-beul, or “mouth music” – a way of singing the melody of a reel, jig, march, or other instrumental piece. In this context, and in Dodge’s hands, the harp is bold, forceful, and nimble, especially in its rhythmic qualities, and she aligns her vocals with it on five tracks of puirt-à-beul that include an epic march-strathspey-reels set – “A’Sheana Bhean Bhochd (Poor Old Woman)” – and a vigorous jig medley, “Dh’fhalbhainn Sgiobalta (I Would Go Quickly)”; fiddles and step dance accompaniment add further heft.

“Cànan na Teud” also includes examples of the Gaelic song tradition, such as the flat-out gorgeous “Tha mo Bhreacan Dubh fo’n Dìle (My Dark Plaid Is Soaked)” and “Càite Bheil i ann am Muile (Where Is She on Mull?),” a haunting lament of longing for a much-desired, elusive woman of beauty.

There is a North American dimension to “Cànan nan Teud” in that the tunes and songs are found in the Cape Breton music tradition, which, while strongly linked to that of Scotland, has cultivated its own identity – as anyone who has spent time (and Dodge has) at the Canadian-American Club in Watertown could tell you.

Quick primer: Essentially, puirt-à-beul is to Scottish/Cape Breton music what lilting is to Irish; both have traditionally been used to accompany dancers in the absence of musicians, although they often serve as performance pieces in their own right. Whereas lilting uses improvised vocables, puirt-à-beul lyrics are mainly actual Gaelic words that are specifically fixed for each tune. The enunciation of these words, along with the melody, are what give a tune/song its distinctive rhythm and sound: They lead the dancers through specific steps and figures, and offer guidance to musicians on phrasing, ornamentation, and other elements of the tune.

Puirt-à-beul lyrics can be repetitive and sometimes fragmentary – there’s seldom a “narrative,” per se – but they are also replete with bawdiness, political satire, light comedy, and nursery rhyming (there are English translations given in the album’s sleeve notes). For Dodge, that’s part of the appeal.

“What I love about puirt-à-beul is the clear, direct, and undeniable link between language, speech rhythms, and traditional music,” wrote Dodge in an email. “The language of the strings to me, is Gaelic; this is the source from which the music and the culture arises and the carrying stream that binds the community and passes the richness of tradition along.”

Unfortunately, she adds, Scottish Gaelic is in a very vulnerable spot right now, with a low number of speakers (about 60,000) and considerable obstacles to ensuring that it is passed onto successive generations.

So it’s worth noting that three of the tracks on “Cànan nan Teud” include a chorus of Dodge’s Cape Breton friends: the aforementioned “Tha mo Bhreacan Dubh fo’n Dìle” and two songs done a cappella, including the album’s final track, “A’Ruma Bàn (The White Rum).” Also accompanying Dodge are spouses Jenny and Kenneth MacKenzie- on step dance and fiddle, respectively- and Rosie MacKenzie on fiddle and backing vocals (some may know her as a co-founder of the Cape Breton band The Cottars). Their presence serves as a reminder of the music tradition’s social nature – these are not obscure, remote activities, but have long helped provide the basis for community.

In that same spirit, Dodge recorded the album in an old parish hall on Cape Breton – the album’s inside sleeve includes a photo of her and the chorus of friends in mid-song, seated around a couple of long tables, the hall’s little stage at the back. It was in many ways, she explains, a philosophical decision: Modern performance and recording studio practices too often separate dancers from musicians, and musicians from one another, killing “the responsive conversation” between all in favor of what she terms a “sterile, mechanical but ‘perfect’ sound.”

She adds, “I'm into bringing the music and the language and the culture back into the same room, the musicians and the dancer back into the same room, and restoring the scattered pieces to their intended whole.”

[dominiquedodge.com]