February 6, 2020

Two of the most accomplished and revered Irish singers of the past half-century (give or take a few years have added to their discographies in recent months:

Andy Irvine, “Old Dog, Long Road Vol. 1” • If you haven’t already been thoroughly impressed, mesmerized or just plain gob-smacked by Irvine’s body of work over the years, then this double-CD set will do the trick; heck, you’ll appreciate it even if you’ve memorized everything in the Irvine catalogue from “As I Roved Out” to “Way Out Yonder.”

Andy Irvine, “Old Dog, Long Road Vol. 1” • If you haven’t already been thoroughly impressed, mesmerized or just plain gob-smacked by Irvine’s body of work over the years, then this double-CD set will do the trick; heck, you’ll appreciate it even if you’ve memorized everything in the Irvine catalogue from “As I Roved Out” to “Way Out Yonder.”

“Old Dog” comprises rare, mostly heretofore unreleased recordings – made in studios, concert halls, pubs, and even at home – dating from 1961, when he was still a promising young actor (with TV and film appearances alongside the likes of Peter Sellers and Laurence Harvey), to 2012, by which time he had established his considerable legacy not only as a gifted singer but as an innovative musician capable of integrating seemingly disparate musical genres (Irish, Balkan, American/old-timey), an astute collector and skillful arranger of traditional ballads, and an eloquent songwriter who draws on historical figures, social issues and his own life experiences.

“Old Dog, Long Road” is not a greatest hits-type compilation: There’s no “Never Tire of the Road,” “My Heart’s Tonight in Ireland,” “The Blacksmith” or “Indiana.” But you get solo versions of “Viva Zapata,” “Sweet Lisbweemore,” “Bonny Light Horseman” and “Kilgrain Hare,” certainly no less deserving of attention, as well as “King Bore and the Sandman” (taken from the “Rainy Sundays/Windy Dreams” album), which demonstrates Irvine’s well-crafted sense of humor. In addition to solo tracks, there are others that offer tantalizing glimpses of, or antecedents to, his renowned partnerships, such as with Johnny Moynihan (Sweeney’s Men), Donal Lunny (Planxty, Mozaik), Rens van der Zalm (Mozaik) and Gerry O’Beirne, Kevin Burke and Jackie Daly (Patrick Street).

One thing this album underscores is just how strongly Irvine was influenced by American folk music in his younger days – in particular Woody Guthrie, whose “upside-down” harmonica style (a welcome presence on much of “Old Dog”) Irvine learned – and how it has remained a part of his musical identity even as he explored other vistas: from the brush-style Carter Family guitar stroke, as heard on 1971 recordings of him playing Guthrie’s “Lost Train Blues” and “Dublin Lady” (which Irvine co-authored with American poet Patrick Carroll), to his renditions of “The Titanic” (recorded 2012) and Guthrie’s poignant, autobiographical “Seamen Three” (1981). A must-listen is his take on “Truckin’ Little Baby,” a Blind Boy Fuller song he taped at home in 1961 – complete with bluesy guitar accompaniment and affected American accent.

“Old Dog” is not arranged chronologically, and that’s one of its many virtues. Sure, on the one hand it would be interesting to witness Irvine’s musical development over time – how did he progress from straight-backed American-style guitar to melodic, intricate bouzouki, or from old-timey songs in 2/4 to Bulgarian tunes in 7/16 – all the while equally at home in traditional Irish instrumental music? But the non-linear sequence of tracks drives home the point that all these incarnations of Irvine, instead of being temporary destinations along the way, remain present in the man, even if some are more readily seen than others.

Besides, it makes for some fascinating and revealing juxtapositions. For instance, on the second disc there is a live track of Irvine and Zalm (on fiddle) playing “Chetvorno Horo,” displaying Irvine’s prowess on bouzouki; this is followed by an astounding home recording from 1968 of Irvine singing an American traditional song, “Reuben’s Train,” with modal, old-timey mandolin; and then a cut from “Rainy Sundays/Windy Dreams,” as Irvine (on mandolin, harmonica and hurdy-gurdy – the latter sadly gone now from his instrumentation) sings the splendid “Longford Weaver,” joined by Lunny, Frankie Gavin on fiddle and Rick Epping on jew’s harp, and segueing into a wonderful turn on the reel “Christmas Eve.”

Dedicated Irvine fans, of course, no doubt have their own wish-list of rarities they’d like to hear, and some may wonder about the absence of one prominent Irvine collaborator here: Paul Brady. It bears pointing out that “Old Dog” is in fact sub-titled “Volume 1,” and in the liner notes Irvine writes, “If this album is well received, there will be a clatter more!” Hard to imagine Volume 2 being able to meet the standard set by 1, but many of us would love to find out for ourselves. [andyirvine.com]

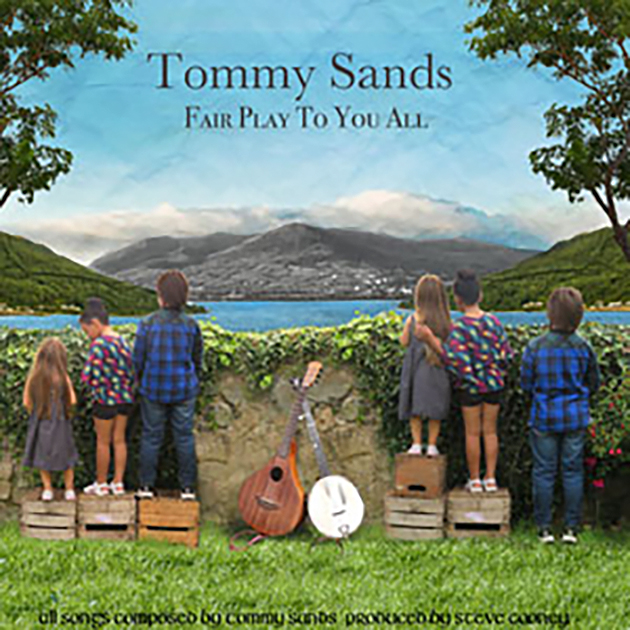

Tommy Sands, “Fair Play to You All” • Calling County Down native Sands a “folk singer-songwriter” aptly illustrates the limits of labels and categories. For decades, he has not just composed songs that advocate peace, fellowship and understanding, he has lived them: leading rallies in support of the Northern Irish peace process; teaching underprivileged prisoners to use songwriting as a tool to defend themselves in court; assisting with interfaith initiatives in the Middle East; and, recently, writing music and songs for a theatrical production in which survivors of The Troubles – including people who lost loved ones to violence, and a former British soldier who served two tours in Northern Ireland – tell their own stories.

Tommy Sands, “Fair Play to You All” • Calling County Down native Sands a “folk singer-songwriter” aptly illustrates the limits of labels and categories. For decades, he has not just composed songs that advocate peace, fellowship and understanding, he has lived them: leading rallies in support of the Northern Irish peace process; teaching underprivileged prisoners to use songwriting as a tool to defend themselves in court; assisting with interfaith initiatives in the Middle East; and, recently, writing music and songs for a theatrical production in which survivors of The Troubles – including people who lost loved ones to violence, and a former British soldier who served two tours in Northern Ireland – tell their own stories.

Seen in this light, Sands’s songs, including, arguably, his two most famous ones, “There Were Roses” and “Daughters and Sons,” are innately personal statements, reminders that conflict and resolution ultimately rest on individual decisions and actions. At the same time, Sands looks for the universality in a given situation or event, whatever its unique dynamics. His commentary is not without some sharp edges, but Sands isn’t interested in giving diatribes or sermons, just appealing to our common, if imperfect, humanity.

All of these qualities are present in “Fair Play to You All,” his first album since 2009. The titular phrase appears in the gentle “Clanyre Side,” a quintessential Sands creation in which he recalls a local pub from earlier days where people from different sectarian and political backgrounds mingled; there was, he writes in the liner notes, “a higher quality of disagreement which allowed for functioning neighbourliness.”

Insight gleaned from random, improbable encounters also is at the heart of “Ballyholland,” as Sands, through the memory of a chance meeting with a County Down ex-pat in Boston, muses on how a family name can tie one to the home left behind. Along similar lines, “Refugees” connects the Irish diaspora to the plight of contemporary migrants: “Roving, a-roving, a-roving, thunder, sun or rain/How did we get here, and where do we go?/When will I see you again?”

Sands also aims to challenge complacency, acquiescence, and an inability or unwillingness to see a bigger picture. “The Answer Is Not Blowing in the Wind” is a deconstruction, of sorts, of that classic Dylan song referenced in the title (“How many times can a cannon ball fly, before they’re forever banned?/Well, they’ll fly just as long as there’s fortunes to be made by the wheelers and dealers of arms”). “Who Killed JFK?” was inspired, according to Sands, by the controversial James W. Douglass book “JFK and the Unspeakable,” which expounds a conspiracy by Kennedy’s security apparatus. Sands, however, is not so much asking us to believe the theory as to ponder the importance of questioning accepted wisdom (i.e., it’s bigger than JFK). “What’s Going on in Jerusalem?” evokes the complexities, and ironies, of the Israeli-Palestinian question filtered through one Jewish family’s history.

But there are lighter sides, too: “Paddy and the Judge” is a modern-day folk tale/fable, with a nice little dig at the legal system and the immortal line, “You know this is sedition/to be fishing so maliciously”; “Every County on the Island” is an epic work of groan-inducing puns and wordplay based on Irish place names – “Keep your head down in the Carlow in case that he is near/And the light down in your Wicklow in case he sees us here” (it’s actually funnier to listen to these than to read them).

And above all, there is optimism and a call to be our better selves, as proclaimed in “Ode to Europe,” to the tune of “Ode to Joy” (“Sow the seed of justice so that we can walk in fields of peace/Sow the seeds of love so that our children's children can be free”) and “Gathering of the Clans” (“They’ll be here from every land with a plan for the clan/And a way to their own way to freedom/And if we can’t agree we can always let it be”).

Sandss’ voice is softer now, but no less expressive – and is supported here and there by members of his family. But it’s the words that matter, obviously, and his hand is as sure now as it’s ever been. [tommysands.com]