September 23, 2020

Hannah Harris, “Tea for Tunes” • A native and resident of Michigan who – you may have heard this one before – started out as a classical violinist but became enamored of Irish fiddling enough to make it the focus of her music. She wound up at University College Cork, where she got a master’s degree in ethnomusicology and, as you might expect, got to know the local traditional music community. While she describes her style as a cross between Kevin Burke and Denis Murphy, Harris by no means confines herself to the repertoire or qualities of Sligo and Sliabh Luachra, or for that matter, purely traditional tunes – on this album, she incorporates compositions from Liz Carroll, Brendan Callaghan, and David Doocey, as well as from friends and acquaintances, and her own pen. Fiddle isn’t her only talent: She’s an accomplished singer.

As a result, “Tea for Tunes” is a thoroughly enjoyable listening experience: intimate, with spare instrumentation, but shrewdly arranged to bring some variety to the proceedings. There’s absolutely no hint of any “I’m-an-American-playing-Irish-music!” self-consciousness; Harris comes across as someone for whom the Irish tradition is a starting point, not a destination.

There are some fine medleys, such as the three reels which open the album: "The Flooded Road to Glenties" (Jimmy McHugh), "Martin Wynne's No. 2" and "Joe Tom" (John Faulkner); her bowing on the lower strings on "Martin Wynne's" in particular is a thing of beauty. A trio of jigs – "Hughie's" (Hughie Kennedy), the traditional "Sliabh Russell" and "Raspberry Ice Cream" (Derry Akin) – is similarly well constructed, especially the transition from the A-dorian intensity of "Sliabh Russell" to the affability of "Raspberry Ice Cream." Another Akin creation, "Fresh Out of the Clouds" – replete with infectious accents and syncopations – caps off a reel medley that includes "Lord Ramsay's" and Liz Carroll's "Potato at the Door." Harris's Sliabh Luachra background comes to the fore on a smattering of polkas, "Glen Cottage No. 1/Cutting Bracken/Little Diamond,” while her bowing takes on a distinctly American character for yet another Akin tune "Tuesday Night," before heading into Sean Ryan's "Glen Aherlow" and "Sweater Weather" by another Harris associate, Stephanie Cope.

Accompanying Harris on most of the tracks is guitarist John Warstler, who clearly knows his way around traditional or “in-the-tradition” tunes; his pass chords on the A part of "Joe Tom" inject a nifty bit of tension alongside Harris on the melody. Harris varies the sound by having the aforementioned Cope join her on piano for "Stephanie's Waltz" (also written by Cope) and on fiddle for a Harris original, "Peeling Potatoes" – Cope goes back and forth between melody, harmony, and rhythm, and it's often quite mesmerizing – which ventures into David Doocey's "Man from Dunblane," Cope switching over to bodhran.

Harris displays a soft yet limber voice for the album's four songs: John Spillane's haunting "Passage West," graced by Warstler's sensitive guitar and harmony vocals; the traditional "Banks of the Lee" (which old Silly Wizard fans will likely appreciate), perhaps a little faster-paced than it needs to be; and two unaccompanied numbers, "Lough Erne's Shore," associated with the legendary Paddy Tunney, and "Carraig Aonair," on which she demonstrates a considerable command of the sean-nos style.

"Tea for Tunes" is what the title suggests: an easy-going, warm indulgence that you'll find easy to accept – even if you usually prefer coffee. [hannahharrisceol.com]

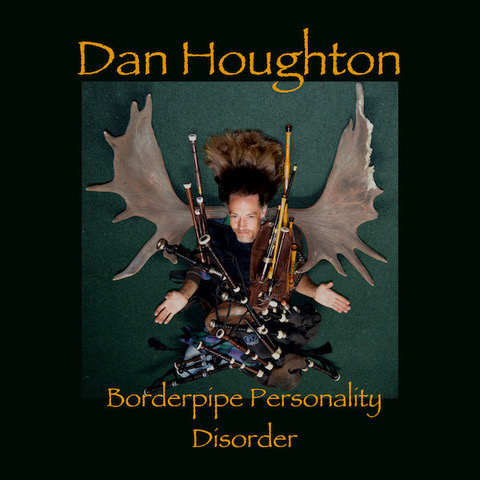

Dan Houghton, “Borderpipe Personality Disorder” • Houghton is a tall, well-traveled gent residing in the wilds of southwestern Vermont who, along with a sly sense of humor, possesses a multiplicity of talents for Celtic music. For one thing, he plays enough instruments – and all very well, too – to be simultaneously his own pipe band and folk ensemble: Highland bagpipes, border pipes, small pipes, flute, whistle, guitar and bouzouki. He also is deft at arranging these instruments, and others played by various friends, in quite inventive and ambitious ways. Among his various collaborations over the years, he’s been part of Cantrip, Salsa Celtica, and Boston-based Parcel of Rogues. Oh yeah, he sings, too – in Scots Gaelic as well as English.

Dan Houghton, “Borderpipe Personality Disorder” • Houghton is a tall, well-traveled gent residing in the wilds of southwestern Vermont who, along with a sly sense of humor, possesses a multiplicity of talents for Celtic music. For one thing, he plays enough instruments – and all very well, too – to be simultaneously his own pipe band and folk ensemble: Highland bagpipes, border pipes, small pipes, flute, whistle, guitar and bouzouki. He also is deft at arranging these instruments, and others played by various friends, in quite inventive and ambitious ways. Among his various collaborations over the years, he’s been part of Cantrip, Salsa Celtica, and Boston-based Parcel of Rogues. Oh yeah, he sings, too – in Scots Gaelic as well as English.

“Borderpipe Personality Disorder” is Houghton’s first full-length recording in 10 years, and while a pandemic may not seem the best circumstances for an album release, the sheer energy, creativity, and boldness evidenced here is a veritable tonic for the times. Most of the 11 tracks are like mini-suites, some lasting anywhere from six to upwards of nine minutes.

For instance, there’s “All Strathspeys All the Time,” as grand a showcase as any for that eminently Scottish dance rhythm, climaxed by not one but two iterations of “Moneymusk,” in different keys; Gloucester native Emerald Rae’s fiddle helps raise the goosebumps. “The Rejected Suitor and his Skinny Legs” set features some classic Scottish tunes, like “Rejected Suitor,” “Jenny’s Picking Cockels” and – following a rocking bouzouki intro (not a sentence you might be used to reading) – “The Swallow’s Tail,” with Houghton starting out on whistle and adding Highland pipes for further enlivenment; the early part of the track includes an outstanding small pipes duet between Houghton and Iain MacHarg. Houghton’s fretted-string dexterity is in the spotlight at the outset of “The Horny Grey Goat,” as he plays melody as well as rhythm on bouzouki (on separate tracks, of course) for “Boc Liath nan Gobhar is E ag Iarraidh Mnà (The Grey Buck Goat).”

The instrumental piece de resistance could easily be “Fuaim man Tonn,” which begins with a pibroch – sometimes described as Scottish bagpipes’ version of classical music – on double-tracked Highland pipes, segues into the march “Campbell’s Caprice” (Houghton on small pipes) and hits the accelerator for “Colonel MacLeod” and “Duntroon Castle.”

Houghton’s deep, somewhat granular singing voice is particularly well suited for Robert Burns’ historical Jacobite ballad “The Battle of Sheriffmuir,” the centerpiece a triptych that starts with his Highland pipes solo on the march “Alba Bheadarach (Beloved Scotland)” associated with the battle and concludes with “Théid Mi Dhachaigh Chrò Chinn t-Sàile (I Will Go Home to Kintail),” a post-battle lament that Houghton sings to the accompaniment of the great pipes – a very potent production overall.

He does an equally imaginative turn on “Mad Tom of Bedlam” (also known as “Bedlam Boys”), a vivid, disturbing depiction of madness first published in the 17th century and famously associated with Steeleye Span’s 1971 recording. Amidst the verses, Houghton interpolates a Breton tune, “La Danse des Condamnés (Dance of the Condemned),” on pipes and bouzouki along with Dan Frank’s electric bass, evoking Alan Stivell’s pioneering Celtic French folk-rock.

Archie Fisher’s much-covered comely but bittersweet love song “Dark Eyed Molly” gets a new luster as well. Houghton maintains the recurring riff from Fisher’s original – based on a Basque tune Fisher used for the melody – but mixes in a suitably melancholy Phil Cunningham tune, “Findlay MacRae.” And with “Blackbird” (the original title is “Bury the Blackbird Here”) Houghton pays tribute to late New England poet Judith “J.B.” Goodenough, a frequent collaborator with Maine singer Gordon Bok; as a complement, Houghton plays the Irish hornpipe of the same name.

As noted, Houghton doesn’t do this completely on his own. In addition to Rae, MacHarg, and Frank, there are appearances by Tristan Henderson, whose jaw harp makes for an intriguing companion for Houghton’s bagpipes on “Drink, Debauchery and 200 Pounds,” and Rachel Clement, with a lovely harp backing for Houghton’s Gaelic singing on “Uaimh an Oir (The Cave of Gold).” But whether produced on his own or with accompanists, Houghton’s albums certainly do not lack for fullness, and strength, of sound. [pipingtool.co.uk]