December 30, 2020

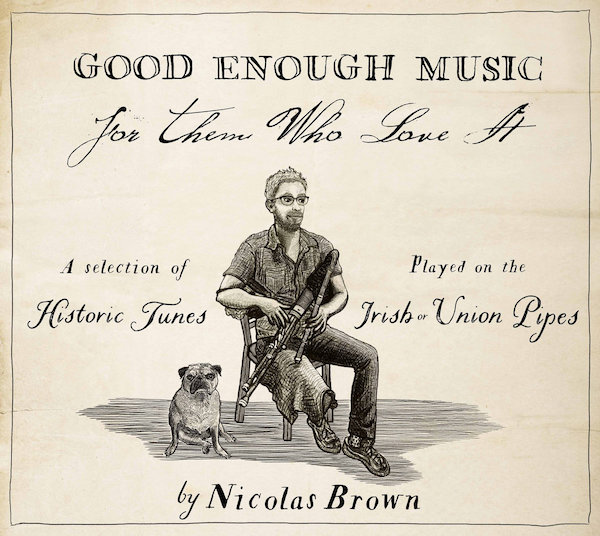

Nicolas Brown, “Good Enough Music for Them Who Love It” • Talk about devotion to historical authenticity: When Brown, a Detroit-based uilleann piper of considerable talent and accomplishment (he and his wife, the fiddler Alison Perkins, released the wonderful album “All Covered with Moss” in 2017), came into possession of a set of antique pipes a few years ago, he set himself the task of learning and recording tunes that would’ve been current around the time the pipes were made – roughly the latter half of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Nicolas Brown, “Good Enough Music for Them Who Love It” • Talk about devotion to historical authenticity: When Brown, a Detroit-based uilleann piper of considerable talent and accomplishment (he and his wife, the fiddler Alison Perkins, released the wonderful album “All Covered with Moss” in 2017), came into possession of a set of antique pipes a few years ago, he set himself the task of learning and recording tunes that would’ve been current around the time the pipes were made – roughly the latter half of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

“Good Enough Music” is less about form than it is about content: Instead of trying to recreate how pipers from that period would played a set like his, Brown seeks to convey what they might have played. A dedicated scholar as well as musician, Brown champions in particular the work of the legendary O’Farrell (Peter or Patrick; his first name has been lost to history), a pioneering piper of the 18th century whose “Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes” has been an invaluable resource for Brown and many others. In fact, almost everything on this album is from the Pocket Companion, although Brown points out some tunes were duplicated from, or appeared in, other publications of the era.

In his research, Brown found the repertoire of pipers during the latter 18th-early 19th centuries was quite rich and surprisingly diverse, and by no means limited to strict national boundaries: O’Farrell and his contemporaries were known to play tunes from Scotland, England, and even farther afield. The tracks on “Good Enough Music” are full of “lost” gems – tunes that, for whatever reason, did not retain their currency or popularity in folk/traditional circles. Some have a familiar tint, like the jig-march “Lanstrum Poney” (sometimes known as “Langstern/Langstrom’s Pony”), which Brown feels was intended for highland pipes – in fact, he tinkered with his pipes slightly to approximate the sound. “The Black Bird” he presents here is not the set dance or air most of us likely associate with the name, but a lovely slow air that showcases Brown’s outstanding use of regulators, the keys on the pipes’ drones that can be utilized to play chords, harmony, even rhythm.

Then there are nuggets like a zesty set of jigs with equally striking titles: “The Life We Love/Bung Your Eye/Lovely Mally” – the last has an A part that’s to die for (the B part isn’t so bad, either); a pair of waltzes, “The Salamanca/The Waterford,” the first of which contains fleeting passages evoking that city’s Spanish character; and a trio of reels that includes “The Pretty Lass,” which Brown explains has quite the backstory – it was actually written in a different time signature and related to “The Town of Ballybay,” a tune not only played as a reel and a song, but also as a Newfoundland single, a kind of modified Irish polka (got all that?).

Arguably the album’s highlight is three excerpts from “The Beggar’s Opera” – satiric musical plays of the period that incorporated folk tunes – of Oscar and Malvina, characters thought to have deep roots in Scottish mythology but actually the invention of 18th-century Scottish writer James Macpherson, who, in turn, drew upon the Irish legend of Finn McCool. Brown notes that O’Farrell participated in the Oscar and Malvina production, hence his inclusion of the tunes associated with it in the Pocket Companion. The Oscar and Malvina selections, on three successive tracks, encompass tunes and arrangements that go beyond what we’ve come to accept as conventional frameworks for uilleann pipes; quite the revelation that such music was played on them more than two centuries ago.

Isn’t a 54-minute album of uilleann pipes rarities kind of on the esoteric side? In a word: nuh-uh. Sure, it helps if you have at least some interest in the pipes, but you needn’t be an expert to appreciate both Brown’s remarkable playing and his in-depth scholarship, as evidenced in his accompanying notes.

“Good Enough Music” also raises interesting, broader topics, such as how, down through the ages, folk and traditional music has intermittently mingled with popular or even “high” culture, vis-à-vis “The Beggar’s Opera”/Oscar and Malvina. And it also may inspire thoughts on how and why some tunes have remained popular in traditional Irish music, while others – like “Lovely Mally” – faded away. Fortunately, there’s always a chance they’ll come back, especially with people like Nicolas Brown around. [pipesandfiddle.com]

Kevin Henderson and Neil Pearlman, “Burden Lake” • Spending part of January hanging around a frozen lake 13 miles due east of Albany, NY, might seem an improbable pathway to artistic inspiration. But Henderson and Pearlman, having grown up, respectively, in Shetland and Maine, are used to chilly scenes of winter. So in the midst of their inaugural tour as a duo two years ago – which included an appearance at the 2019 Boston Celtic Music Fest – they packed themselves off to Rensselaer County to work up some new material.

Kevin Henderson and Neil Pearlman, “Burden Lake” • Spending part of January hanging around a frozen lake 13 miles due east of Albany, NY, might seem an improbable pathway to artistic inspiration. But Henderson and Pearlman, having grown up, respectively, in Shetland and Maine, are used to chilly scenes of winter. So in the midst of their inaugural tour as a duo two years ago – which included an appearance at the 2019 Boston Celtic Music Fest – they packed themselves off to Rensselaer County to work up some new material.

And much as a frozen lake eventually returns to the full spectrum of aquatic life, “Burden Lake” – released almost a year-and-a-half after that January sojourn – is replete with energy, creativity, and invigorating new takes on Celtic and American traditions. Henderson is a leading exemplar of the Shetland fiddle, which incorporates elements of Scottish as well as Scandinavian styles, and a member of bands like the Nordic Fiddlers Bloc, Blazin’ Fiddles, and the Boys of the Lough. Pearlman’s innovative, dynamic piano playing has brought a fresh outlook to Cape Breton accompaniment, adding jazz, Latin, and other modern elements to nudge, push, lead, or gently entwine as necessary; he’s in a duo, and occasional trio, with Westford-born fiddler Katie McNally, and the two of them also are part of the quartet Fàrsan (Pearlman and McNally also co-direct the Boston Scottish Fiddle Club).

Most of the tunes on “Burden Lake” were composed by Henderson and Pearlman, yet are strongly linked to tradition. Henderson’s originals contain key facets of Shetland music, such as varying bar lengths and uneven numbers of bars (a characteristic shared with Swedish and Norwegian music), syncopation and ringing, open-string droning. “Sjovald” and “Tune for Lukas,” among others, display that unique Shetland “swing,” and Pearlman’s piano is right there – seemingly quixotic, going from rhythm to melody and back again in just a few measures, yet always in control.

Pearlman’s portfolio includes a jig-strathspey set, “Gas Station Raptors/The Strat-O-Matic King,” that expresses his Cape Breton/Scottish interests in a contemporary mindset. “San Simon/47 Hours” spotlights Pearlman’s sometimes overlooked ability on mandolin (both as a lead and rhythm instrument), and adds a modicum of Americana to the proceedings. Henderson is certainly no afterthought on either track, though, his presence equally vibrant as throughout the rest of the album.

(Mention must be made, incidentally, of Neil Harland’s subtle but fully present double bass, which appears on all but two of the album’s tracks.)

As the liner notes indicate, these and other originals have personal/familial dimensions in their origins: Henderson wrote one for each of his sons (“Liam’s,” “Tune for Lukas”) and another for a distant “Viking” descendant (“Sjovald”), for instance, while Pearlman pays tribute to Fàrsan bandmates McNally and Mairi Britton (“Gas Station Raptors”) and a childhood friend (“Strat-O-Matic King”).

A few traditional tunes add some useful perspective to the album: the measured, stately “Da Trowie Burn,” and a pair of trademark Shetland reels, “Head Her In for Bastavoe” and “Sillocks and Tatties” (which are joined to Henderson’s “The Magic Roundabout”).

Fittingly enough, the album closes with the title tune, a moderately slow piece by Henderson: He solos the first time through, the fiddle sounding plaintive and remote, and then Pearlman fills in the sound before briefly taking the lead himself; after some improvisation the pair returns to the theme, and to the subdued tone at the beginning – don’t know if it’s what they had in mind, but the overall effect suggests the procession of seasons at, and within, the lake.

It’s difficult not to feel regret that this budding partnership – like so many others, whether new or old – has been sidelined by the pandemic, but hopefully there’ll be a joyful reunion before long, maybe even on the shores of Burden Lake. [kevinandneil.com]