December 28, 2020

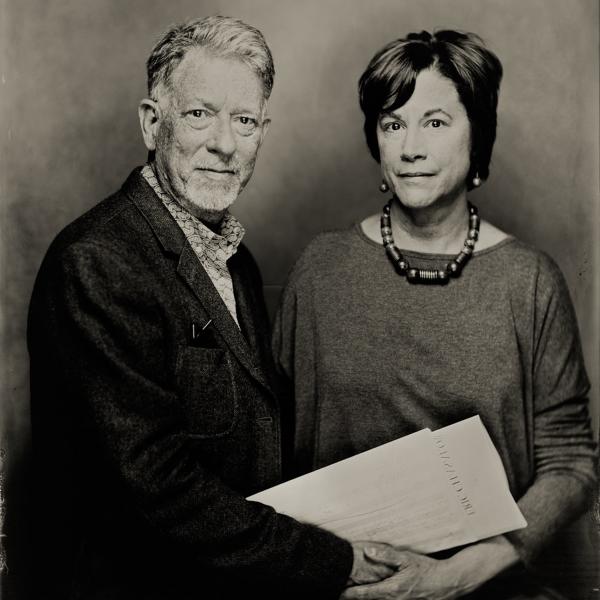

Barbara Cassidy and her husband Eric Chasalow.

Boston-area singer Barbara Cassidy takes the big-picture view when it comes to winter: Sure, darkness comes early, the days are short, the weather outside is frightful, etc., etc., but the season has its virtues.

“You’re inside more, and you tend to slow down,” explains Cassidy, whose musical interests run from Irish and other folk traditions to contemporary and original material. “You get meditative and reflective. You take stock.”

In this spirit of contemplation, Cassidy recently released an EP album, “A Winter Frame of Mind,” its eight tracks reflecting an impressive span of styles and tastes, including songs of the Irish and British Isles traditions, a somewhat obscure composition by one of pop’s most iconic figures, plus two Cassidy originals – one based on a Yeats poem. She’s accompanied throughout by her husband Eric Chasalow, who plays guitar, mandolin, whistle, keyboards, and percussion; they’re joined by some special guests, constituting the ever-shifting make-up of the Barbara Cassidy Band.

“I feel that the album has the grand themes of celebration, life, death and birth, and how you pass through these milestones: What you’ve left behind and what you bring with you,” she says. “It just feels very natural to muse on these sort of things in the winter, what with celebrating the holidays, saying goodbye to the old year, and welcoming in a new one. ‘A Winter of Frame of Mind’ is not a ‘holiday’ album in that sense, although it does touch on Christmas and New Year’s; it puts them in a larger context.”

Cassidy has a substantial pedigree in Irish/Celtic music, having been a student of renowned Irish singer Bridget Fitzgerald and a second-place finisher in the 2013 Mid-Atlantic Fleadh Cheoil’s over-18 women’s English-singing competition; she and Chasalow also helped produce and release Fitzgerald’s 2014 album, “Two Sides of a Coyne.” They’ve appeared at various venues and events in Greater Boston, including the 2014 Feile Cheoil and BCMFest.

But as “A Winter Frame of Mind” suggests, Cassidy’s career has involved numerous artistic pursuits: stage acting and directing; teaching dance; working on PBS science programs; arts festival organizing; and researching and writing about women in American musical theater. While exploring her interest in traditional song from Ireland and elsewhere, she’s continued to work on other aspects of her musical inclinations, notably songwriting; she credits her ongoing conversations with a revolving group of female singers for helping build her confidence as a writer. Having a recording studio at home has enabled Cassidy and Chasalow to develop their sound and repertoire: They’ve released four albums as the Barbara Cassidy Band on their own label, Suspicious Motives.

Not surprisingly, the pandemic provided its own special kind of impetus for Cassidy and Chasalow’s recording projects. “We were going a little stir-crazy,” she says. “I put out a single, ‘Einstein Was Right,’ and Eric released an album of electronic music. All along, we had been working on some songs, putting them to the side. At one point, we said, ‘Maybe it’s time to do a new album.’ That led us to record some newer things in our repertoire.”

The celebratory/holiday elements in “A Winter Frame of Mind” are represented by “The Wexford Carol” – on which Chasalow overlays a soft mandolin backing on his spare guitar accompaniment, along with a slowly building organ drone and an occasional chime from a set of antique cymbals, giving the song a mystical feel – and Robert Burns’ “Auld Lang Syne.” But the tune for the latter, Cassidy notes, “may not be the one you were expecting”: According to some scholars, the melody associated with it in the public mind (see Lombardo, Guy) was affixed to the song after Burns died. The original is, to many ears, less grandiose, more heartfelt – even a little melancholy.

“If you hadn’t grown up with a folk/trad background, you wouldn’t know the story behind ‘Auld Lang Syne,’” says Cassidy. “It blew my mind to hear this version, and put it in a new light for me.”

The songs contributed by Cassidy on “A Winter Frame of Mind” are rooted in classic Irish literature and folk tradition. “A Drinking Song” is her setting of the Yeats poem (“Wine comes in at the mouth/And love comes in at the eye”), short in length but long on the speculation and analysis it has sparked among scholars and poetry devotees. Her Irish singing, with superbly deployed ornamentation, is at the forefront here, next to Chasalow’s tin whistle and guitar aided by fiddler Joe Kessler and mandolinist Jimmy Ryan.

“I had this melody rattling around in my head that I couldn’t get rid of,” she says. “I read this poem a long time ago and it’s been one of my favorites. I never thought in a million years I could do something with these words, but the melody really seemed to mesh with it.”

In composing “I Have a Daughter,” Cassidy took inspiration from some of the darker ballads in the famous Francis .J. Child collection, in particular “The Cruel Mother,” which all by itself refutes the idea of folk songs as archaic, quaint little ditties. In Cassidy’s first-person narrative, a woman reflects on the cruelty inflicted on her by those professing to love her, despite her devotion (“But I was a good girl/And I was always there”); but she vows to create a far better legacy.

“I’ve always had an interest in how women are portrayed in different kinds of music,” says Cassidy. “Child ballads intrigue me in the way women are at the center of the story, but are often only afforded two outcomes: to be a victim or to be evil. What I wanted to express in this song is that from a dark place can come joy; terrible things can happen, but you can still find redemption or reconciliation.”

The remaining four songs include Jimmy Webb’s “All I Know,” about facing the prospect of parting, however reluctantly: “Endings always come too fast/They come too fast/But they pass too slow/I love you and that’s all I know.” Cassidy doesn’t overdo the emoting, just letting the lyrics speak for themselves; there’s a solemn yet stately break that features Chasalow’s guitar dueting with trumpeter Travis Alford. “His Bright Smile Haunts Me Still,” written in 1858 by W.T. Wrighton and J.E. Carpenter, provides a postscript to the parting of ways (“I have struggled to forget/But the struggle was in vain”), and again, there’s appropriate restraint in Cassidy’s delivery, plus a lovely pairing throughout the track of fiddler Hanneke Cassel with Chasalow (on mandola).

“This was a hugely popular song in 1860s America, and even now it’s still being sung in small towns – passed down like traditional songs have been in Ireland,” says Cassidy. “I’m fascinated by how songs continue to speak to us and how they help us express what’s going on inside us, even after so much time. This one really fit the bill.”

Briege’s Murphy’s “Hills of South Armagh” delves into another form of leave-taking, encapsulating the Irish diaspora through the eyes, ears and laments of an émigré in Brooklyn, who wonders out loud whether the changes she sees in her family, and herself, have been worth the whole undertaking.

“It’s very bittersweet, as would be the case for anyone who has had to leave home, and who looks back with worry and concern,” says Cassidy of Murphy’s song. “Of course, as we know, for centuries people have been making a new life in America, and finding success and satisfaction. But it’s also true that there are some things you never quite get over, and leaving home is often one of them.”

Offering a contrast is Paul McCartney’s ebullient “Calico Skies,” which he wrote while stranded on Long Island during Hurricane Bob in 1991; swathed in a giddy waltz tempo, it’s a proclamation of love (“I’ll hold you for as long as you like/I’ll hold you for the rest of my life”) that, as Sir Paul put it, becomes a 1960s protest song with its final verse: “May we never be called to handle/All the weapons of war we despise.”

“I actually thought it was coming from some ‘Irish trad place,’ but in any case, the song just caught me with its optimism, and it’s rhythmically exhilarating,” says Cassidy.

As she has branched out in her singing, Cassidy has often thought about the connections between the musical genres she inhabits.

“It’s not just the stories in the songs that interest me, but the stories of the songs: Where they came from, who wrote them – if that’s known – and how they’ve circulated,” she says. “So, when I decide to learn a song, I not only look at its content, or whether it’s a good match for me and my voice: I’m also thinking, ‘How can I convey the thought behind the song?’

“This is especially true for traditional songs, because when you sing them you are taking on the role of interpreter, as someone who is passing the tradition along. I associate singing traditional songs with dancing: You learn by shadowing, by getting the steps from someone who learned from, say, a Balanchine or a Fosse. I feel very fortunate to have known singers like Bridget who have that gift. It makes you feel that much closer to the music.”

For more on the Barbara Cassidy Band, including recordings, see barbaracassidyband.com.