April 1, 2019

Marcia Palmater is dead at 80

BY SEAN SMITH

SPECIAL TO THE BIR

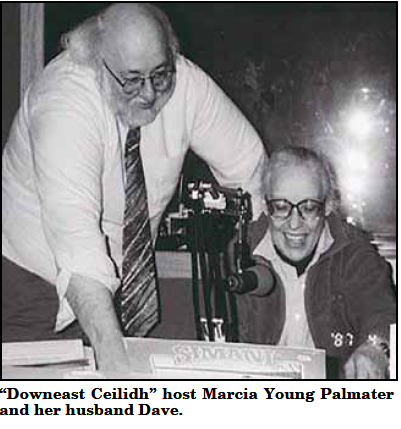

Boston lost one of its foremost Celtic music connoisseurs recently, with the passing of longtime radio broadcaster Marcia Young Palmater on February 9. She was 80.

Ms. Palmater shared her love and encyclopedic knowledge of traditional music from Cape Breton and elsewhere in the Canadian Maritimes as the host and producer of the “Downeast Ceilidh” weekly radio show for more than 40 years.

The program, which ran on WMBR (the MIT radio station) and then WUMB, was a must-listen affair for Boston’s large Nova Scotia and Cape Breton community – as well as ex-pats from Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick – who tuned in to enjoy the music of home.

Later on, as Celtic music grew in popularity, “Downeast Ceilidh” was an important resource for listeners interested in discovering the mainstays of Cape Breton and Canadian Atlantic music traditions like John Campbell, Joe Cormier, Brenda Stubbert, John Morris Rankin, Buddy MacMaster, and Jerry Holland, as well as performers with a contemporary bent, such as Ashley MacIsaac, Natalie MacMaster (Buddy MacMaster’s niece), Mary Jane Lamond, and The Rankin Family.

Yet Ms. Palmater was not from that part of the world: She was a native – and proud – New Englander, born and raised in Concord, NH, who didn’t discover Downeast music until well into adulthood. Nor did she envision herself as a DJ. Still, she thoroughly embraced her role and became a familiar and welcome figure at area Celtic music events – especially those featuring Canadian Maritimes acts, many of them at the Canadian American Club of Massachusetts in Watertown.

The Nova Scotian/Canadian Atlantic community, in turn, embraced Ms. Palmater as one of its own.

“It was a big ritual for families like ours to sit down and listen to ‘Downeast Ceilidh’ when it came on,” recalls Peggy Morrison, a longtime Canadian American Club official, organizer, and member whose parents were among those who immigrated from Nova Scotia to “the Boston States.” “To hear the music and the songs, especially those in Gaelic, was so important to everyone, and Marcia really understood that. She took it on as a great responsibility but you knew it was something she enjoyed doing.”

“Being able to go to a dance or a concert and have everyone know her was very satisfying for Marcia,” says her husband, Dave Palmater, himself a denizen of Boston-area folk music radio for many years. “It got to the point that almost everyone assumed Marcia was from the Canadian Maritimes. She just wanted to give back to the music and the community, and she cherished their acceptance.”

Growing up, Ms. Palmater developed a taste for traditional folk music via contra and square dancing, and expanded her interests upon moving to the Boston area in the late 1960s. She found kindred spirits through the international folk dance crowd at MIT and the Cambridge Folk Orchestra. Along the way, she met Doug McPhee, a bank teller who happened to be a top-notch pianist in the distinctive Cape Breton style. McPhee took her to the Boston Highland Games, where she encountered Boston’s Cape Breton community, which led her to the Canadian American Club. Soon afterwards, Ms. Palmater made the first of many trips up to the island.

“As soon as Marcia got there, she connected the music with the land,” says Dave Palmater. “That was the beginning.”

Not long after that, Ms. Palmater quit her job as copy editor and proofreader, and hitched back to Cape Breton for a more extended stay, getting to know the people as well as the places.

In the mid-1970s, Marcia and Dave– they had gotten married after having met, appropriately enough, at the Passim folk club in Harvard Square – were taking the journey to Cape Breton together: leaving after work on Friday in their VW Bug with a spare tire strapped on top and carrying a 10-gallon can of gasoline (“You weren’t apt to find a lot of gas stations in northern Maine, especially at night,” notes Dave), and returning on Sunday night.

By then, Marcia had embarked on her signature vocation. Through a friend, she got involved in the MIT radio station (WTBS, later WMBR), long a haven for folk and country music. Having had experience producing a radio show on conservation, she thought about recruiting someone with Canadian Maritime ties to host a program on Canadian Maritimes music that she would produce. But then she reconsidered, and on Thurs., Feb. 3, 1972, “Downeast Ceilidh” debuted – with Ms. Palmater behind the microphone.

“Her idea was that the show might have more impact with someone not from Atlantic Canada presenting it,” explains Dave. “At the time, the music of the region was dismissed, even by those who lived there, as ‘home music’ or some quaint antiquity that was of no interest to anyone but natives. Having the show hosted by someone not from the Maritimes would help show that this music was beautiful, important, and worth listening to – even if you weren’t a Maritimer.

“Just getting the music on the radio not only exposed it to a wider audience who had never heard it, but it also helped elevate it in the eyes of folks from Atlantic Canada,” adds Palmater, who recalls the time when a young man told Ms. Palmater that one of the musicians she’d featured was a family member: “Until I heard your show I never knew he was famous,” he said to her. “I just thought he was my weird uncle.”

Ms. Palmater would play recordings of old masters as well as new-generation musicians and contemporary artists from the region. The show also included songs in Gaelic and Acadian French, and others in English that were traditional to the area or recent compositions.

The core feature of “Downeast Ceilidh” was Cape Breton/Nova Scotian fiddlers and fiddle styles, for which Ms. Palmater developed an in-depth knowledge. “Marcia could tell just by listening where a fiddler was from,” says Dave. “She would file her Cape Breton albums geographically – Mabou, Sydney, etc. – instead of alphabetically by the fiddler’s name.”

But Ms. Palmater evinced a folksy manner on the air – as she did off it – rather than that of a scholar, talking about the artists whose albums she played as if they were friends and acquaintances, which many were. She made a point of specifying where a musician or singer came from, notes Dave: Rita and Mary Rankin were not just from Cape Breton, for example, and not just from Mabou but from Mabou Coal Mines.

“To Marcia,” he says, “even a couple of miles made a difference.”

Instead of beginning the show with a spoken introduction, Ms. Palmater would typically welcome listeners by playing three or four musical selections, an interval that might last as much as 10 minutes or more; only then would she come on and announce the show’s title.

“Marcia felt the program was primarily for the Canadian American community,” says Dave. “If anyone else tuned in, that was fine. She just wanted to put the music out there from the get-go, have the listeners focus in on it.”

During its run on MIT radio, Ms. Palmater insisted that “Downeast Ceilidh” begin at 6 p.m., because she thought that would be the ideal time to reach Maritimers. It was sound reasoning. Once, at the Canadian American Club, says Dave, a surly-looking teenager came up to her and said he regularly listened to “Downeast Ceilidh.” When Ms. Palmater expressed surprise at this, he replied, “Yeah – if I want to eat dinner on Thursdays, I have to.”

To its dedicated corps of Canadian American listeners, says Dave, it wasn’t “Downeast Ceilidh” but simply “Marcia’s Show.” About every Maritimer’s home in Greater Boston he and Marcia visited seemed to have a note pinned to the refrigerator with a reminder of the day and time for “Marcia’s Show.” At one home was a note on the TV: “Don’t watch on Thursday evenings!”

When the show moved to WUMB – where her husband also worked – and to Sunday nights, Dave printed up refrigerator magnets with the station and schedule information. During the program, Marcia would offer to send them to listeners who provided a self-addressed stamped envelope.

“Between the ones we sent out and the ones we handed out, I must have printed up hundreds,” says Dave. “I wonder if there are any left, still stuck to a fridge door.”

Morrison says Ms. Palmater understood the reach her show had, and its potential for promoting the music. “Marcia would always call around the first of the month to ask who was coming down from Cape Breton, where they’d be playing, when the Canadian American Club would be having a concert or a dance, so that she could make sure to mention it and to play their music on the show.”

Ms. Palmater made a point of getting to know the musicians of earlier generations, like Bill Lamey, who organized dances for Boston-area Maritimers during the 1950s and ’60s. “She’d love doing that,” says Morrison, “and she made it exciting for the people talked to – they were happy to have the opportunity to talk about the music and what it meant to the community. It was lovely to watch.”

At the same time, Ms. Palmater helped to widen the audience for Canadian Atlantic music. When she began “Downeast Ceilidh,” there had been few recordings of Cape Breton music issued in “a very long time,” says Dave; but not long after she began broadcasting, Rounder Records, which was associated with MIT radio, started a Cape Breton series. She also was attuned to the new generation of performers who were reviving the Maritimes tradition, or taking it in new directions.

“Without Marcia, a lot of stuff wouldn’t have happened,” Dave explains. “Natalie MacMaster, as a young teen, could play down here and people knew about her because they knew her family’s music. And, of course, her popularity went well beyond the Maritimer community.”

In recent years, as Ms. Palmater’s health declined, she stopped doing the show live and recorded it at home with her husband’s help. When that proved to be too difficult for her to undertake, Dave edited previous “Downeast Ceilidh” programs for re-airing, until he retired from WUMB in 2017. Many episodes are now available online at ceilidh.org and at folktracks.blog.

Even as the scope and influence of “Downeast Ceilidh” grew, Ms. Palmater treasured the personal connections the show had forged from the beginning. “Early on in the life of the program, she got a call from a homesick young Maritimer who was in tears,” recalls Dave. “He never thought he’d not just hear the music of home, but the name of the little place that he came from on the radio in Boston.”

Donations in Marcia Young Palmater’s memory can be made to The Canadian American Club, Marcia Young Palmater Building Fund , 202 Arlington St., Watertown, MA 02474 or online at canadianamericanclub.com/Membership-and-Donations.html .