August 1, 2019

Four Greater Boston teen musicians

– and 8,000 other competitors –

are heading to Drogheda for Fleadh 2019

BY SEAN SMITH

SPECIAL TO THE BIR

The four of them have each been to the All-Ireland Fleadh Cheoil at least once, and they’re all set to go again. They know very well the amount of work it takes to get to the world’s biggest Irish music competition and appreciate the opportunity. And none of them is old enough to drive yet.

Headed to this year’s Fleadh, which takes place in Drogheda from Aug. 11 to Aug. 18 – sponsored by Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, the global Irish cultural organization – are 12-year-old Niamh McGillicuddy of Milton, 15-year-old Seamus Noonan of Maynard, and brothers Yuriy (13) and Misha (15) Bane of Walpole; all of them qualified after winning or placing second in their respective categories at the Mid-Atlantic Fleadh Cheoil held June 7-9 in Parsippany, NJ. They’ll join some 8,000 musicians who will take part in competitions and other events, including impromptu sessions that spring up in parks and on street corners, or anyplace else where there’s space.

Other Greater Boston/Eastern Massachusetts-area musicians who qualified include Jonathan Ford (tin whistle, slow airs on whistle, newly composed dance songs, slow airs on fiddle); Bailey Ford (piano); Noah Kelly (slow airs on fiddle) and Wynter Pingel (concertina).

Every Fleadh-going musician, of course, no matter what age, has his or her own special qualities that have contributed to success. In the case of these four young musicians, they all have a familial connection to Ireland, as well as to the music, and – key ingredient here – supportive parents. Most of all, they have by now arrived at a place where Irish music is more than lessons and rehearsals, or another obligation to fulfill; it’s something they own, a part of themselves that demands time and attention – both of which they are happy to give.

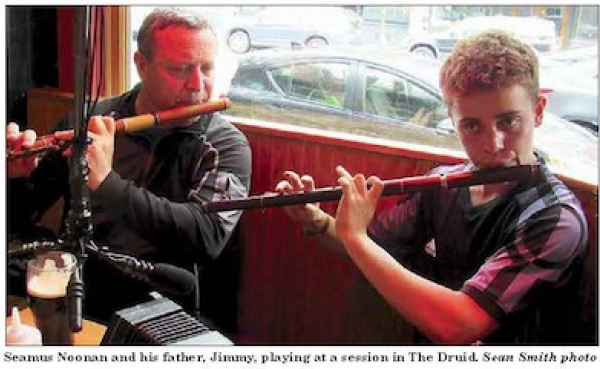

“It’s like having a second life,” says Seamus, who plays flute and concertina and will be competing in the former category at this year’s All-Ireland Fleadh, his sixth. “When you go off to a session, you end up meeting and hanging out with people you probably wouldn’t meet otherwise. Playing Irish music just expands your world like that.”

“Playing the concertina is definitely a stress reliever when you’re anxious,” says Niamh, who in addition to the concertina competition also will play in a duet with Misha at her third straight All-Ireland. “When I play it, I don’t have to think about that test I’ve got coming up on Monday. But I like playing the music for itself, like when you’re in a duo or trio: You communicate and bounce off each other even while you’re focusing on each other; they’ll cover for you, and you’ll cover for them. It’s a great feeling.”

“I just like having the ability to join other people, literally anywhere in the world, in sharing Irish culture and music,” says Yuriy, a whistle player, who along with brother Misha is bound for his second Fleadh.

Obviously, you don’t have to compete in the Fleadh to be able to experience all that. There are plenty of musicians who have excelled in Irish music, or have gotten good enough to find satisfaction in playing it, without going the competition route. Those who do compete tend to view the process as a milestone or a point of reference to help sort out their progress, and to affirm their feelings and attitudes about the Irish music tradition.

As Misha notes, competition can be a means for instilling self-discipline. “You stay focused on what you’re doing, and don’t worry about the other musicians,” he says, repeating advice his and Yuriy’s teacher, Dennis Galvin, has given them. “Find a spot to look at when you play, and you won’t see your surroundings, so you won’t be distracted.”

For her part, Niamh says she hasn’t gone through Fleadh-related jitters: “Everyone reacts their own way,” she says, with a smile. “I don’t know, I just don’t get nervous – I get an adrenaline rush.”

But the competition is only one aspect of the All-Ireland Fleadh: There are classes and workshops with master musicians and dancers, concerts featuring some of Irish music’s best performers (this year’s line-up includes Téada with Seamus Begley, Eleanor McEvoy, Damien Dempsey, Zoë Conway, Sean Keane, the Martin Hayes Quartet, Cherish the Ladies and Kevin Burke), and many, many sessions. The streets are fairly bustling with tourists, so an enterprising young musician can do pretty well busking – which is what Misha and Yuriy plan on doing together.

In recent years, the Fleadh has reached an international audience via the Internet, broadcasting some of their special concerts as well as on-the-street interviews and performances with Fleadh competitors.

“My first Fleadh was a real eye-opener,” recalls Niamh. “I’d never been to a festival that big in my life. And there were so many kids playing music. It was a great way to make friends and pick up some ideas and inspiration. I really like the classes, where you get to learn from different instructors – they each make you look at the music in a different way.”

The All-Ireland Fleadh can be eye-opening in another way, as Seamus found his first time there. Witnessing the high quality of the Irish-born competitors in his category got to him, he acknowledges: “I just completely lost it on the first pass. I was too nervous.”

“It’s a revelation to see the kids from Ireland,” says Seamus’s father, Jimmy Noonan, an accomplished flute and whistle player born in the US whose father was from Clare. “In Ireland, just about all they do is practice; they learn instruments in their schools, and they have sessions and ceilis to go to all the time. And to qualify for the All-Irelands, every kid has to compete not only in the county but also in the provincial fleadhs, so they have to be really, really good.”

But Seamus didn’t let his initial breakdown defeat him. He sampled the other features of the Fleadh, made friends, and sat in with more experienced, and older, musicians. Back home, he took part in the Youth Trad Exchange co-organized by Boston’s Comhaltas branch music school, through which young musicians mainly from Greater Boston were matched with peers from County Clare; each group spent time in the other’s country, playing and performing together. Fortified by these and other experiences, he subsequently played far better at the competitions.

“Before, music was work,” summarizes Seamus, who cites the Trad Youth Exchange in particular as foundational to his development. “And then it wasn’t a chore. I wasn’t only playing, I was listening to a lot more music, like what Dad has on his iPod. That really helps you a lot.”

Although he once qualified for the All-Ireland, Jimmy Noonan never took to competing – “I would just get too nervous” – but he thought it might be beneficial for Seamus, who early on showed an interest in playing (Seamus, like Misha, also learned Irish dance at an early age, which helped familiarize them with the music). Still, Jimmy didn’t push things.

“I always told Seamus just to learn the music, and to pass on the music,” says Jimmy. “And then he got good. So the Fleadh seemed like something to try for. He saw what it was all about, how competitive it is, and how that drives up the standard for the music. He gets it. What he’s doing now is beyond what I ever did.

“I’m just happiest when I hear him sit down with his friends and play great music.”

Niamh – who started on fiddle and tin whistle at age five – says her father’s side of the family was active in Irish music, including her grandfather, who played concertina and thus gave her the motivation to follow suit. She understands there is something beyond the immediacy of learning tunes or practicing one’s technique, and credits her teacher, Florence Fahy, for helping her see that.

“Flo likes me to know where a tune came from, which musicians would play it, or who composed it,” she explains. “She wants me to be able to answer the question, ‘What’s that you’re playing?’”

Misha and Yuriy’s father, Frank, had an accordion-playing brother whose musical partners included Boston Irish music legend Billy Caples. Although more familiar with American traditional music, Frank took up the box himself, and when the boys were young he would bring them around to Irish sessions until they began playing themselves. Now, Frank – whose wife Mary, a Kerry native, further solidifies the family’s Irish heritage – is not too proud to admit that Misha and Yuriy have progressed beyond him (“If we’re playing with Dad, we have to slow down,” Misha quips).

Frank recalls advice he once received from a professional musician on the parental role in helping children get involved in music: When kids are very young, they have only a vague notion of what playing music entails, so parents make the decisions – instrument, genre of music, teacher, practice times, and so on.

“It’s your gift to them,” says Frank. “You give them that regimen, those hours, rides to and from lessons. But eventually, it’s the kids who have to decide what part, if any, music will play in their lives.”

For information about this year’s Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann, see fleadhcheoil.ie.