September 1, 2018

BY SEAN SMITH

BIR CORRESPONDENT

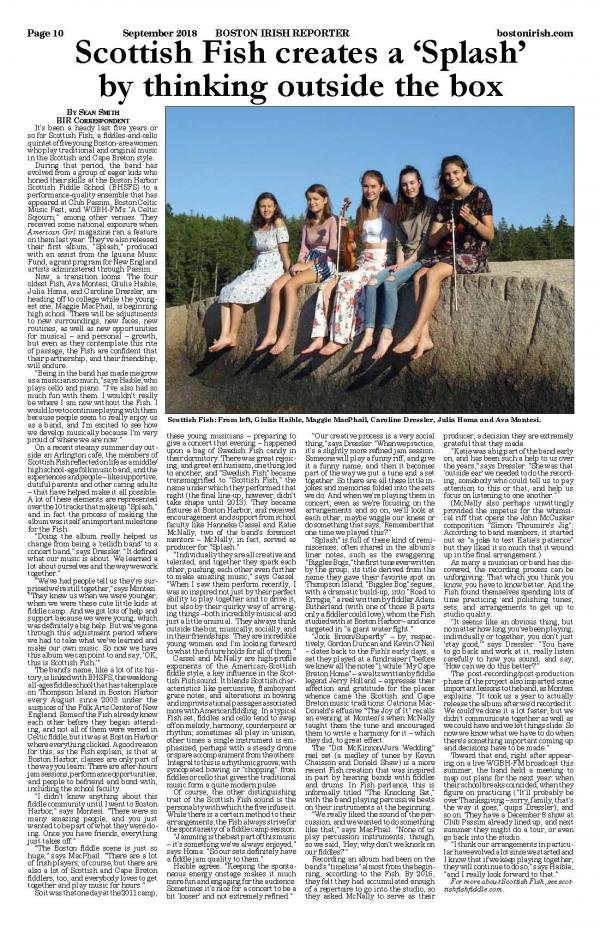

It’s been a heady last five years or so for Scottish Fish, a fiddles-and-cello quintet of five young Boston-area women who play traditional and original music in the Scottish and Cape Breton style.

During that period, the band has evolved from a group of eager kids who honed their skills at the Boston Harbor Scottish Fiddle School (BHSFS) to a performance-quality ensemble that has appeared at Club Passim, Boston Celtic Music Fest, and WGBH-FM’s “A Celtic Sojourn,” among other venues. They received some national exposure when American Girl magazine ran a feature on them last year. They’ve also released their first album, “Splash,” produced with an assist from the Iguana Music Fund, a grant program for New England artists administered through Passim.

Now, a transition looms: The four oldest Fish, Ava Montesi, Giulia Haible, Julia Homa, and Caroline Dressler, are heading off to college while the youngest one, Maggie MacPhail, is beginning high school. There will be adjustments to new surroundings, new faces, new routines, as well as new opportunities for musical – and personal – growth, but even as they contemplate this rite of passage, the Fish are confident that their partnership, and their friendship, will endure.

“Being in the band has made me grow as a musician so much,” says Haible, who plays cello and piano. “I’ve also had so much fun with them. I wouldn’t really be where I am now without the Fish. I would love to continue playing with them because people seem to really enjoy us as a band, and I’m excited to see how we develop musically because I’m very proud of where we are now.”

On a recent steamy summer day outside an Arlington café, the members of Scottish Fish reflected on life as a middle/high school-age folk music band, and the experiences and people – like supportive, dutiful parents and other caring adults – that have helped make it all possible. A lot of these elements are represented over the 10 tracks that make up “Splash,” and in fact the process of making the album was itself an important milestone for the Fish.

“Doing the album really helped us change from being a ‘ceilidh band’ to a concert band,” says Dressler. “It defined what our music is about. We learned a lot about ourselves and the way we work together.”

“We’ve had people tell us they’re surprised we’re still together,” says Montesi. “They knew us when we were younger, when we were these cute little kids at fiddle camp. And we got lots of help and support because we were young, which was definitely a big help. But we’ve gone through this adjustment period where we had to take what we’ve learned and make our own music. So now we have this album we can point to and say, ‘OK, this is Scottish Fish.’”

The band’s name, like a lot of its history, is linked with BHSFS, the weeklong all-ages fiddle school that has taken place on Thompson Island in Boston Harbor every August since 2003 under the auspices of the Folk Arts Center of New England. Some of the Fish already knew each other before they began attending, and not all of them were versed in Celtic fiddle, but it was at Boston Harbor where everything clicked. A good reason for this, as the Fish explain, is that at Boston Harbor, classes are only part of the way you learn: There are after-hours jam sessions, performance opportunities, and people to befriend and bond with, including the school faculty.

“I didn’t know anything about this fiddle community until I went to Boston Harbor,” says Montesi. “There were so many amazing people, and you just wanted to be part of what they were doing. Once you have friends, everything just takes off.”

“The Boston fiddle scene is just so huge,” says MacPhail. “There are a lot of Irish players, of course, but there are also a lot of Scottish and Cape Breton fiddlers, too, and everybody loves to get together and play music for hours.”

So it was that one day at the 2011 camp, these young musicians – preparing to give a concert that evening – happened upon a bag of Swedish Fish candy in their dormitory. There was great rejoicing, and great enthusiasm, one thing led to another, and “Swedish Fish” became transmogrified to “Scottish Fish,” the name under which they performed that night (the final line-up, however, didn’t take shape until 2013). They became fixtures at Boston Harbor, and received encouragement and support from school faculty like Hanneke Cassel and Katie McNally, two of the band’s foremost mentors – McNally, in fact, served as producer for “Splash.”

“Individually they are all creative and talented, and together they spark each other, pushing each other even further to make amazing music,” says Cassel. “When I saw them perform recently, I was so inspired not just by their perfect ability to play together and to drive it, but also by their quirky way of arranging things –both incredibly musical and just a little unusual. They always think outside the box, musically, socially, and in their friendships. They are incredible young women and I’m looking forward to what the future holds for all of them.”

Cassel and McNally are high-profile exponents of the American-Scottish fiddle style, a key influence in the Scottish Fish sound: It blends Scottish characteristics like percussive, flamboyant grace notes, and alterations in bowing and improvisational passages associated more with American fiddling. In a typical Fish set, fiddles and cello tend to swap off on melody, harmony, counterpoint or rhythm; sometimes all play in unison, other times a single instrument is emphasized, perhaps with a steady drone or spare accompaniment from the others. Integral to this is a rhythmic groove, with syncopated bowing or “chopping” from fiddles or cello that gives the traditional music form a quite modern pulse.

Of course, the other distinguishing trait of the Scottish Fish sound is the personality with which the five infuse it. While there is a certain method to their arrangements, the Fish always strive for the spontaneity of a fiddle camp session.

“Jamming is the best part of this music – it’s something we’ve always enjoyed,” says Homa. “So our sets definitely have a fiddle jam quality to them.”

Haible agrees. “Keeping the spontaneous energy onstage makes it much more fun and engaging for the audience. Sometimes it’s nice for a concert to be a bit ‘looser’ and not extremely refined.”

“Our creative process is a very social thing,” says Dressler. “When we practice, it’s a slightly more refined jam session. Someone will play a funny riff, and give it a funny name, and then it becomes part of the way we put a tune and a set together. So there are all these little in-jokes and memories folded into the sets we do. And when we’re playing them in concert, even as we’re focusing on the arrangements and so on, we’ll look at each other, maybe wiggle our knees or do something that says, ‘Remember that one time we played this?’”

“Splash” is full of these kind of reminiscences, often shared in the album’s liner notes, such as the swaggering “Biggles Bogs,” the first tune ever written by the group, its title derived from the name they gave their favorite spot on Thompson Island; “Biggles Bog” segues, with a dramatic build-up, into “Road to Errogie,” a reel written by fiddler Adam Sutherland (with one of those B parts only a fiddler could love), whom the Fish studied with at Boston Harbor – and once targeted in “a giant water fight.”

“Jock Broon/Superfly” – by, respectively, Gordon Duncan and Kevin O’Neil – dates back to the Fish’s early days, a set they played at a fundraiser (“before we knew all the notes”), while “My Cape Breton Home” – a waltz written by fiddle legend Jerry Holland – expresses their affection and gratitude for the places whence came the Scottish and Cape Breton music traditions. Catriona MacDonald’s effusive “The Joy of It” recalls an evening at Montesi’s when McNally taught them the tune and encouraged them to write a harmony for it – which they did, to great effect.

The “Dot McKinnon/Jura Wedding” reel set (a medley of tunes by Kevin Chaisson and Donald Shaw) is a more recent Fish creation that was inspired in part by hearing bands with fiddles and drums. In Fish parlance, this is informally titled “The Knocking Set,” with the band playing percussive beats on their instruments at the beginning.

“We really liked the sound of the percussion, and we wanted to do something like that,” says MacPhail. “None of us play percussion instruments, though, so we said, ‘Hey, why don’t we knock on our fiddles?’”

Recording an album had been on the band’s “timeline” almost from the beginning, according to the Fish. By 2016, they felt they had accumulated enough of a repertoire to go into the studio, so they asked McNally to serve as their producer, a decision they are extremely grateful that they made.

“Katie was a big part of the band early on, and has been such a help to us over the years,” says Dressler. “She was that ‘outside ear’ we needed to do the recording, somebody who could tell us to pay attention to this or that, and help us focus on listening to one another.”

(McNally also perhaps unwittingly provided the impetus for the whimsical riff that opens the John McCusker composition “Simon Thoumire’s Jig”: According to band members, it started out as “a joke to test Katie’s patience” but they liked it so much that it wound up in the final arrangement.)

As many a musician or band has discovered, the recording process can be unforgiving: That which you think you know, you have to know better. And the Fish found themselves spending lots of time practicing and polishing tunes, sets, and arrangements to get up to studio quality.

“It seems like an obvious thing, but no matter how long you’ve been playing, individually or together, you don’t just ‘stay good,’” says Dressler. “You have to go back and work at it, really listen carefully to how you sound, and say, ‘How can we do this better?’”

The post-recording/post-production phase of the project also imparted some important lessons to the band, as Montesi explains. “It took us a year to actually release the album after we’d recorded it. We could’ve done it a lot faster, but we didn’t communicate together as well as we could have and we let things slide. So now we know what we have to do when there’s something important coming up and decisions have to be made.”

Toward that end, right after appearing on a live WGBH-FM broadcast this summer, the band held a meeting to map out plans for the next year: when their school breaks coincided, when they figure on practicing (“It’ll probably be over Thanksgiving – sorry, family, that’s the way it goes,” quips Dressler), and so on. They have a December 8 show at Club Passim already lined up, and next summer they might do a tour, or even go back into the studio.

“I think our arrangements in particular have evolved a lot since we started and I know that if we keep playing together, they will continue to do so,” says Haible, “and I really look forward to that.”

For more about Scottish Fish, see scottishfishfiddle.com.