November 30, 2018

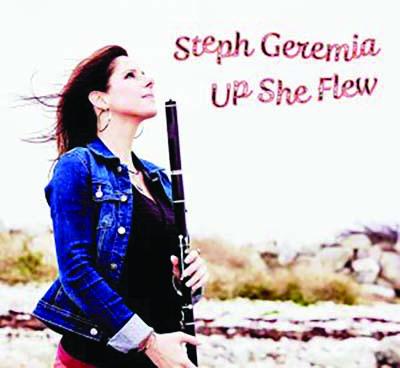

Steph Geremia, “Up She Flew” • New York City’s Geremia, now living in Galway, is familiar to many for her fine flute and whistle-playing and vocals with the Alan Kelly Gang. But her musical development may not be, and is quite fascinating: In college, where she studied world music, she worked with experimental jazz multi-instrumentalist Anthony Braxton; then she spent time in India learning the bonsuri flute, before moving to Ireland and becoming conversant in the Sligo-Roscommon flute tradition; she also holds a master’s degree in traditional Irish music performance from the University of Limerick. Oh, and she developed a taste for salsa and jazz while living in Italy during her youth, and as a teenager, was a featured soloist in various orchestras.

Appropriately enough, “Up She Flew” – Geremia’s second solo album and her first in nearly a decade – has the stamp of a confident, versatile musician who, with the assistance of an astute co-producer (Donal O’Connor, who also plays keyboards) and with various combinations of accompanists, presents her artistry by striking a balance between flair and imagination with obvious affection for the tradition.

Most of all, she can play up a storm, not only with demonstrably excellent technique but an ear for subtle variations and flourishes that keep listeners engaged – especially those who may not be flutophiles or even that fond of instrumental stuff in general. Tracks like the set of reels which opens the album (including her own “Benbulben’s Shadow”), or the jig medley of “The Spider’s Web/The Housemaid/Dominic’s Farewell to Cashel” are full of these goodies, as is the one that features two hornpipes (a different setting of the well-known “Blackbird” plus “Murphy’s”) – you gotta love musicians who, instead of treating hornpipes as slow reels, tease out all the rhythmic treats they offer.

“Up She Flew” also benefits from some outstanding backing musicians, with Aaron Jones (bououzki), Seamie O’Dowd (guitar, bouzouki), Jim Higgins (bodhran, percussion), and Martin Brunsden (double bass) the most frequently appearing; others include Michael Rooney (harp), Ben Gunnery (fiddle), and Alan Kelly (accordion). But they are deployed in such a way as to create a variety of tones and moods, and work very well under the direction of Geremia and O’Connor.

One sterling example is the album’s trio of polkas, with Jones providing a pulsing, syncopated beat at the start (Charlie Lennon’s “Island Polka 3”) that Higgins picks up in the middle tune, “I’ll Buy Boots for Maggie” (with its distinctive B part); there’s a brief, somewhat eerie interlude led by Geremia’s double-tracked flute and Jones’ bouzouki, and then everyone’s back on the polka train for a Shetland tune, “Baak-High.” By contrast, Rooney and Gunnery create a suitably sylvan feel for Maurice Lennon’s “Rossiver Waltz” and a Swedish mazurka, “Vals E Anon Egeland” – Gunnery’s fiddle is multiply tracked on the latter, making it all the more charming.

Geremia brings in a whole other dynamic by playing soprano sax on two other tracks, a jig-reels set (“Moon Man/Old Grey Gander/Lucky in Love”) – Kelly’s accordion is a perfect complement – and a trio of reels (“Martin Wynne’s #3 and #4/Bring Her to the Shelter”) that starts with a flute-harp duet and ends in a jazzy, Moving Hearts c.1980s-style mode. She also gives a tantalizing sample of her assured singing on the emigration song “Path Across the Ocean,” O’Connor’s electric piano supplying a moody, spare undercurrent.

It’s one thing to have accumulated such varied experiences and influences, but Geremia has a gift for using these to embellish and enrich, rather than muddy, the Irish music tradition she’s embraced. [stephgeremia.com]

The Tannahill Weavers, “Órach” • The Irish and English folk revivals tend to get most of the attention, but Scottish music also has enjoyed a renewal during the past few decades, and The Tannahill Weavers played no small role in it. The “Tannies,” whose origins go back to the late 1960s, was the first professional Scottish band to incorporate full-sized Highland bagpipes in performance, and over the course of the 1970s built a following – not only in the UK but Europe and the US as well – through an energetic, arena-ready stage presence as well as top-form musicality. Co-founders Roy Gullane (vocals, guitar) and Phil Smillie (flute, whistles, bodhran, vocals) continue to hold forth, along with John Martin (fiddle, viola, cello, vocals) and Lorne MacDougall (Highland bagpipes, small pipes, whistle).

“Órach” is the Tannahills’ five-decade-commemoration album, and has a lot of the characteristics one would expect from such a milestone, such as appearances from past members like Dougie MacLean, Mike Ward, Hudson Swan, and the estimable Alan MacLeod, and guest stars Alison Brown and Aaron Jones, among others. Yet while the 14 tracks carry various associations and memories from over the years, this is hardly a rehash of “greatest hits” by a band getting long in the tooth; on the contrary, the Tannahills show their creativity and zest for playing is as strong as ever.

The lads long ago transitioned from an emphasis on high-octane, adrenaline-producing sets to a more measured approach that relies as much on well-crafted arrangements to bring out the aesthetic qualities of Scottish music. And they’re as skillful as ever at it, as demonstrated by the march-strathspey-reel medley title track that opens the album, as well as a gorgeous air, “Sunset Over the Somme” (written by piping legend G. S. MacLennan), on which MacDougall is joined by former Tannahill pipers Colin Melville, Kenny Forsyth and Iain MacInnes, with MacLean’s fiddle adding heft. There’s also a set of tunes popularized by another former band member, the late Gordon Duncan, an innovative piper and tune composer, and Dubliner John Sheahan’s lovely “Christchurch Cathedral,” which spotlights Smillie’s fine flute-playing. The Tannies even go the world-music route on a track that delves into music from Spain’s Celtic-affiliated Asturian tradition, with an appearance by Asturian band Llan de Cubel.

One virtue of the Tannahills that continues to hold true is their rich, exquisitely-voiced harmony singing, much in evidence on the album’s songs, of which there are some intriguing choices: “The Jeannie C,” a maritime tragedy written by the late, beloved Stan Rogers, with whom the Tannies performed on their very first North American tour; the countryish “Oh No!’ by Billy Connolly, the comedian/actor who once upon a time was a singer-songwriter – rendered here with a don’t-hear-that-everyday duet between Highland pipes and Brown’s five-string banjo; and “Jenny A’Things,” by another departed legend, Matt McGuinn.

On the more traditional side are two songs by the band’s namesake, poet Robert Tannahill, including the vivid, ghostly “Fragment of a Scottish Ballad,” and arguably the album’s centerpiece, the epic, chaotic “Battle of Sheriffmuir” – perhaps the most celebrated literary account of biased reporting – with the piping corps of MacDougall, MacLeod, MacInnes, and Duncan Nicholson helping create the martial tone as Gullane unfurls the dramatic, rapid-fire narrative (thankfully, the lyrics are included in the liner notes).

Those self-same liner notes, incidentally, are another treat of “Órach”: They provide origins and background to the songs and tunes, of course, but also offer some idea of the many personalities and adventures that the Tannies have encountered, individually and collectively, over the course of 50 years. It underscores the fact that the Scottish music revival, like that of its Irish and English cousins, has a grand and distinguished history that deserves to be recognized. [tannahillweavers.com]