February 27, 2019

Patrick Radden Keefe grew up in the heart of Boston’s Irish community— the Adams Corner section of Dorchester. His dad Frank— whose great-grandparents were immigrants from Donegal—was a regular at the Eire Pub.

But despite the name and pedigree, Keefe wasn’t raised like some of his Irish-American cousins who came of age as the Troubles roiled their ancestral homeland. He wasn’t regaled with rebel ballads on the Saturday Irish Hour. No plastic paddy, this one.

As he matured, Keefe— a Milton Academy graduate— read the news about the latest bombings, gun attacks, and then the breakthrough peace process of the late 1990s as though Ireland were was just another foreign country.

That level of detachment, it turns out, may have served him well.

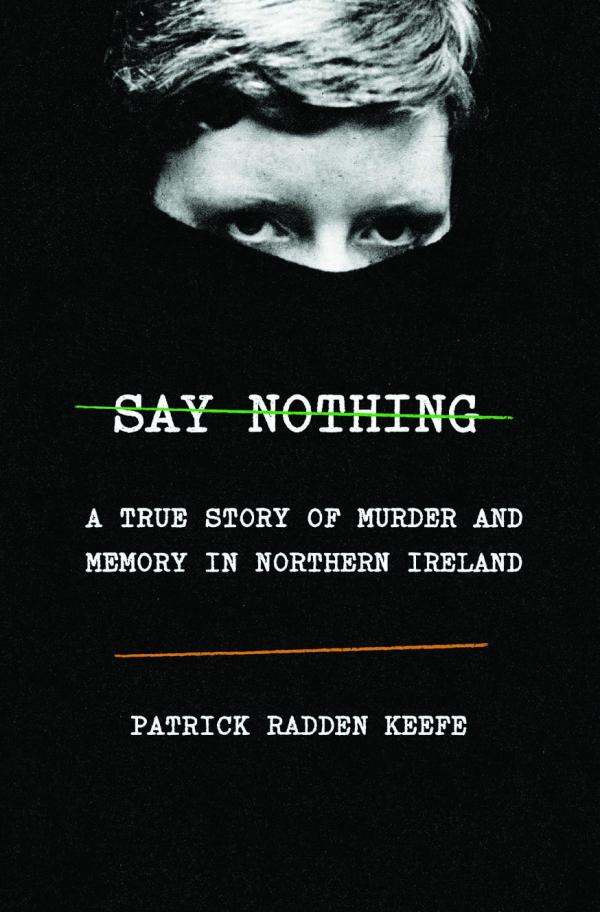

In his new book, “Say Nothing,” the 42-year-old staff writer with the New Yorker dives deep into one of the most notorious killings in the civil war: the murder and disappearance of Jean McConville, a mother of 10 who was snatched from her Belfast family by the IRA in 1972. The book recounts the events and participants in a narrative that will grip even those well versed in the story. And— without giving away Keefe’s ending— he breaks new ground in theorizing about the gunman who he believes delivered the fatal blow to McConville, whom the IRA believed was a “tout”— or snitch.

Keefe, who now lives in New York, began reporting on the McConville case in 2014. Like many journalists, he was drawn in by the controversy surrounding the Boston College Belfast Project, the well-intentioned oral history effort based in the university’s Irish Studies program. It was thrust into notoriety after police in the UK discovered that audiotapes with paramilitary participants might provide new evidence into the McConville case. In particular, they wanted tapes in which former IRA soldiers Brendan Hughes and Delours Price allegedly described the McConville abduction, murder, and cover-up in granular detail.

While the legal wrangling involving BC was his entrée into the case, Keefe found himself hooked by the characters’ people like Hughes, Price, and IRA commander-turned-Sinn Fein politician, Gerry Adams. (Adams has consistently denied involvement in the IRA, but as Keefe repeatedly notes, there’s ample evidence that he was, in fact, a leading figure in the organization.)

After writing a piece on the case for the New Yorker, Keefe decided to dive deeper into a book project. While he had visited Ireland once before to discover his family roots in the Republic, he found that his surname and gene pool mattered little to the people of Derry and Antrim and Belfast, where his research for the book was centered.

“I kept thinking it would [hamper me] and it didn’t. I went in thinking, some folks might talk to me because I’m Patrick Keefe. But I was an outsider. The Irish name didn’t matter. They rarely asked me about the roots. As soon as I opened my mouth— accents play a huge role- it marked me as an outsider. And that ended up being a big advantage. It was a little harder to pigeon

hole me,” said Keefe.

Sources in the North of Ireland are, by nature, insular and disinclined to reveal much about the past unpleasantries. The challenge was compounded by the fact that many principal players in the McConville story “felt pretty burned by the Boston College project.”

But Keefe could point to his New Yorker portfolio as his “calling card.” The piece he had already written on the McConville case and the BC Belfast project was straight down the middle.

“I could give it to people and say I don’t have an agenda here,” he said.

One person who refused to talk to Keefe for the book is a central figure: Gerry Adams. “He’s a tricky character and I think a part of what was most appealing to me about writing this book were the characters— Delours Price, Brendan Hughes, Adams,” said Keefe. “They’re outsized, complicated figures. I don’t think there are any real straightforward villains. You get to the end of the book, and you can relate to these people.”

Keefe manages to strike a fair balance on Adams. He leaves no question that Adams was a central figure in the IRA and was likely intimately familiar with the McConville war crime. But, as author puts it: “You also see that he was the guy who had the foresight to see around the corner in a way that many others couldn’t.”

Adams, of course, never participated in the ill-fated BC Belfast project. In fact, its existence was shielded from Adams and other higher-ups in the Republican movement for that very reason: He likely would have sought to shut it down.

The fact that people like Hughes and Price, both deceased, did participate spoke to the rift that had developed between Adams, a key player in moving toward ceasefire and peace, and hard-liners who saw a rapprochement as a surrender.

Part of the reason people like Hughes and Price participated— at risk of implicating themselves in unsolved crimes— was because “they felt Gerry Adams and people around him were trying to create a definitive history of the Republican struggle and one that they felt misrepresented the past.

“There had been this code of silence for so long,” Keefe said. “But everyone wants to tell their story at the end of the day.”

We will leave it to readers to dive into Keefe’s work and discover some of his more intriguing theories about those actually responsible for murdering Jean McConville. Others close to Keefe’s hometown might find this essential reading by virtue of its focus on the Boston College angle, which in Keefe’s telling, is an “unfortunate one.”

“The BC project started with a really noble and sound ambition. You’ve had this awful tragedy and we want to create a historical record and leave aside accountability. Instead, it becomes a political football used in a selective way and the people you did want to have use it — people who really want to understand and make sense of it and write about it—will never get to use it. It created a chilling effect for people to talk about the past.”

“Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland” by Patrick Radden Keefe went on sale in the United States on Feb 26.