April 27, 2018

Having marked its 25th anniversary year in the fall of 2016, the Burns Visiting Scholar in Irish Studies program is in the midst of another landmark semester: The spring 2018 Burns Scholar, Jason Knirck, is the first American to hold the professorship. As part of his activities, Knirck organized a symposium at Boston College in April spotlighting the work of American-educated historians of Ireland.

A collaboration between the Boston College Center for Irish Programs and University Libraries, the Burns Scholar program brings outstanding academics, writers, journalists, librarians, and other notable figures to the University to teach courses, offer public lectures, and work with the resources of the Burns Library in their ongoing research, writing, and creative endeavors.

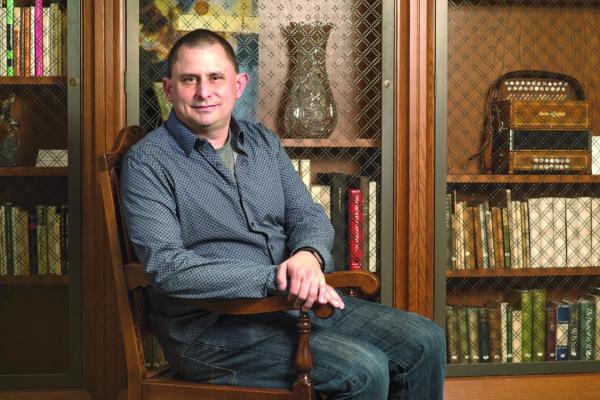

Knirck is a professor of history at Central Washington University whose research and teaching interests center on events and trends in the Irish revolutionary period of the 20th century and its aftermath — specifically the Irish Free State — as well as Ireland’s complex relationship with the British Empire. Among other topics, Knirck has studied the role of women in revolutionary Ireland, and the advent of political parties in the Irish Free State.

During his time at BC, he has used Burns Library materials and archives for research projects on the Irish Free State era, one about economic and taxation policies, another on the development of loyal parliamentary opposition.

Knirck’s appointment, and the April 7 symposium, “Is There an American School of Irish History,” underscore the vitality of the Burns Scholar program and of Irish Studies at BC, according to Center for Irish Programs Director James Murphy, himself a former Burns Scholar.

“We are delighted to have Jason Knirck with us this semester as Burns Scholar,” says Murphy. “His selection as the first American-trained and based scholar of Ireland to hold the Burns Chair is a sign that Irish Studies has come of age in the United States. One of my goals is to make Irish Studies at Boston College a home for Irish history in the US, and I feel the conference will be a major step in that direction.”

“BC’s eminent reputation in Irish Studies, especially as one of few universities offering doctorates in Irish history, is well-deserved,” says Knirck, whose past research was supported by funding from Boston College Ireland. “I’ve been fortunate to meet a lot of people associated with the program and now, having the opportunity to be at the Burns Library and to teach BC students, my appreciation has deepened.”

The Knirck-organized symposium brought together scholars of Ireland who were all trained in the US and have taught Irish history. The participants – at various stages of their careers, from graduate students to tenured professors and administrators – shared their research and gathered for a roundtable on the place of Irish history in the American academy, and of Irish historians in the US.

Knirck says the “American School” of Irish history that has emerged in recent decades represents a different perspective than that of the scholarship in Irish academia. “If you’re American-born, it means that you’re at a certain remove from the history, because you simply grew up with different influences than someone from Ireland,” he explains. “It doesn’t mean your insight into Irish history is better, or worse, than that of an Irish-born historian — you just see things differently.”

For Knirck, Irish history is not only fascinating in and of itself, but it also provides lenses with which to examine universal questions of how social and political systems develop, and why some succeed and others fail.

The period encompassing Ireland’s 1916 Easter Rising, the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty and subsequent civil war, and the Irish Free State (which lasted from 1922-37) offers much for consideration, says Knirck. But the Irish Free State in particular has received comparatively little scrutiny, and its generally negative image has endured, he says, for several reasons — including a reluctance among scholars to challenge an Irish Republican view of the state as illegitimate, failed, and repressive.

“In post-revolution Ireland, we see a classic dilemma: How do soldiers become statesmen?” says Knirck. “After the struggle with England, and then the pro- and anti-Treaty forces, came the inevitable state-building phase — a bitter process where there were winners and losers, real and perceived. That antagonism endured for a long time, and has colored perceptions of this period.”

As Knirck sees it, the Irish Free State created a stable democratic system that normalized nonviolent political opposition — this despite the fact that the post-Treaty opposition party boycotted the Irish Parliament and supported armed resistance to the new state.

“ Unlike the Rising and the Irish Civil War, the Irish Free State had no real dominant personalities, so there was a shadow hanging over it,” says Knirck, who discussed this topic in a public lecture in April. “But its legacy was the creation of parliamentary norms in a time that was not particularly favorable to democracies.”

This interview was conducted by the Boston College Office of University Communications.